[ad_1]

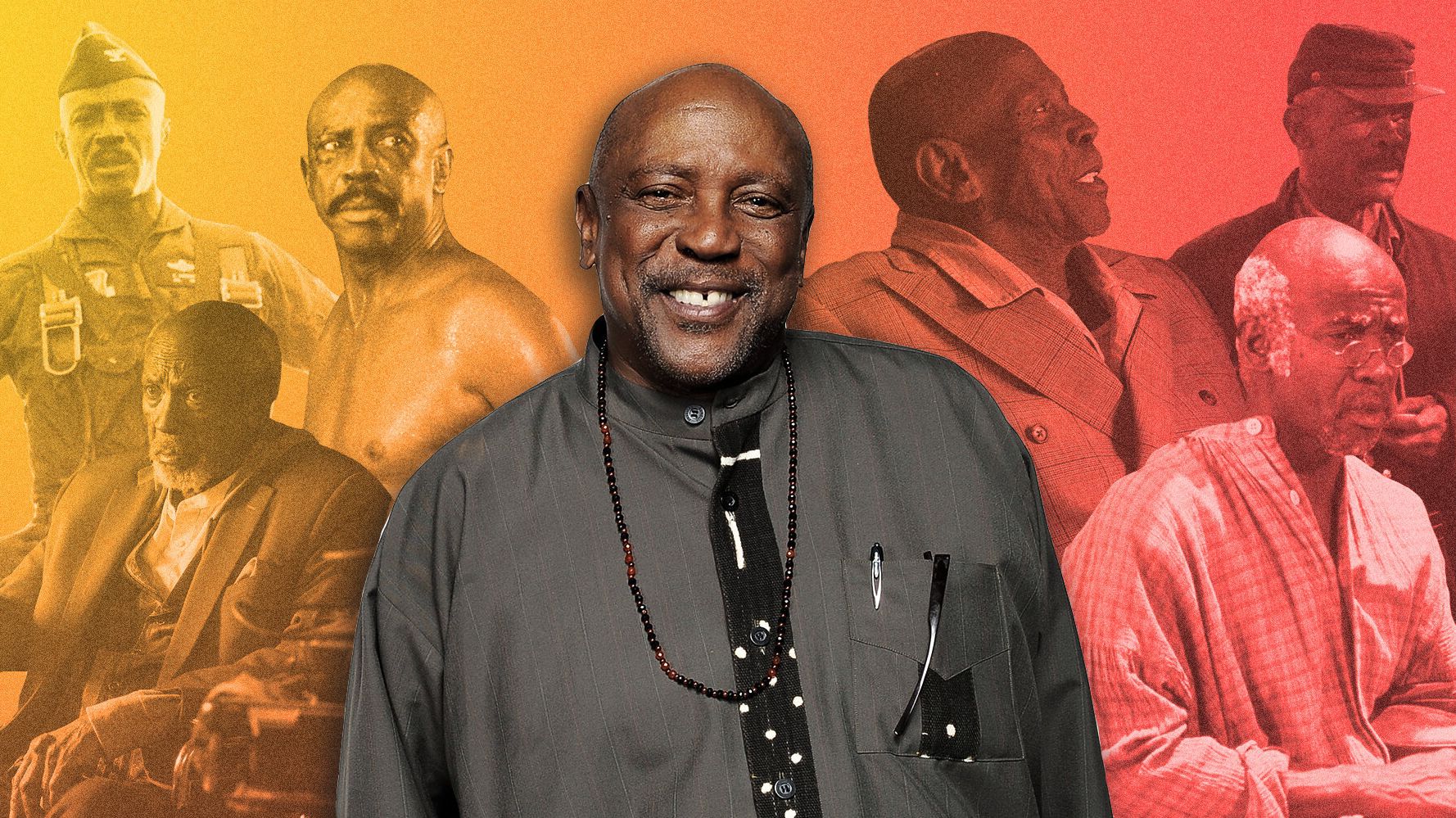

Spend an hour talking to Louis Gossett Jr., and you might hear any or all of the following names: Marlon Brando, Sidney Poitier, Anne Baxter, James Garner, Bob Dylan, Liza Minnelli, James Earl Jones, Harry Belafonte, Maggie Smith, Elia Kazan, Jesse Jackson, Paul Newman. They are friends and colleagues of his, sources of inspiration, evidence of a life well lived. Gossett is 84. He speaks quickly, so the references fly by. Beware of whiplash. Altogether, they’re enough to make you wonder why someone who took acting classes with Marilyn Monroe and made his first movie with Ruby Dee went so long without a role as complex as Will Reeves, the vigilante he portrayed last year on HBO’s “Watchmen.”

Sure, Gossett has been working nonstop in recent years, most notably in two Tyler Perry movies and a bunch of guest spots on shows like “Boardwalk Empire,” “The Good Fight” and the Halle Berry sci-fi drama “Extant.” He seems satisfied in a spiritual sense, and far be it for me to insist that he is lacking anything.

“I’m becoming full circle, almost for the first time since childhood, of being a complete human being going in the right direction,” Gossett said by phone mere days before “Watchmen” earned him his eighth Emmy nomination.

Still, the reverence he has earned within the industry, combined with the breadth of his experience, suggests a more dynamic career trajectory than the one Gossett has actually seen since winning an Oscar for “An Officer and a Gentleman” in 1983.

Here’s a sampling of things people told me about him:

Regina King, his “Watchmen” co-star: “He’s royalty. He’s definitely been a trailblazer for Black actors, especially.”

Delroy Lindo, who shared scenes with Gossett in “The Good Fight” and the 1999 Showtime movie “Strange Justice”: “He came backstage when I was doing a brilliant August Wilson play called ‘Joe Turner’s Come and Gone.’ He said to me, ‘Man, you showed me something tonight,’ which is a huge compliment. Huge. And the fact that it was coming from Louis Gossett Jr. was just icing on the cake. The word that comes to mind is ‘warrior.’”

Sergio Navarretta, director of “The Cuban,” Gossett’s newest movie: “The joy you see on-screen is the joy that I experienced with him off-screen. He’s very playful. He has this infectious charisma that you only see in a great artist.”

Taylor Hackford, director of “An Officer and a Gentleman” who cast Gossett as a merciless Navy officer even though the role was written for a white actor: “I remember one weekend a couple of actors got drunk and got into a car accident, and they called Lou. Lou is their fellow actor, but they called Lou because he was Sgt. Foley, and he dealt with it. I thought that was really indicative: They had the sense that this authority figure would do the right thing, and he did. By the time I got involved, Lou had taken care of business.”

Damon Lindelof, “Watchmen” creator: “My memories of him are in between setups, people gathering around him as he was telling stories about his childhood growing up in New York or plays that he did in the early days. I’m not just saying this to you because you’re writing a piece about him, but he’s a legend. When you’re in the presence of a legend, you just sit back and listen.”

“Watchmen,” a superhero saga with surprising depth, lets Gossett be a sage, an elder who imparts wisdom based on a history of racial strain. (No wonder he held court.) The same goes for “The Cuban,” in which he portrays a downtrodden Alzheimer’s patient who regains his mojo upon hearing the music of his youth. He doesn’t speak much in the film (now available to rent on video-on-demand services), so his eyes do most of the work. Gossett’s eyes have always contained a touch of unquenchable wonder, especially when complemented by his gleeful smile. When deployed in “Watchmen” and “The Cuban,” those features help the two roles seem like lifetime achievement prizes, finally capturing the best of what Gossett can do as an actor.

“It’s a very special time in life,” he said.

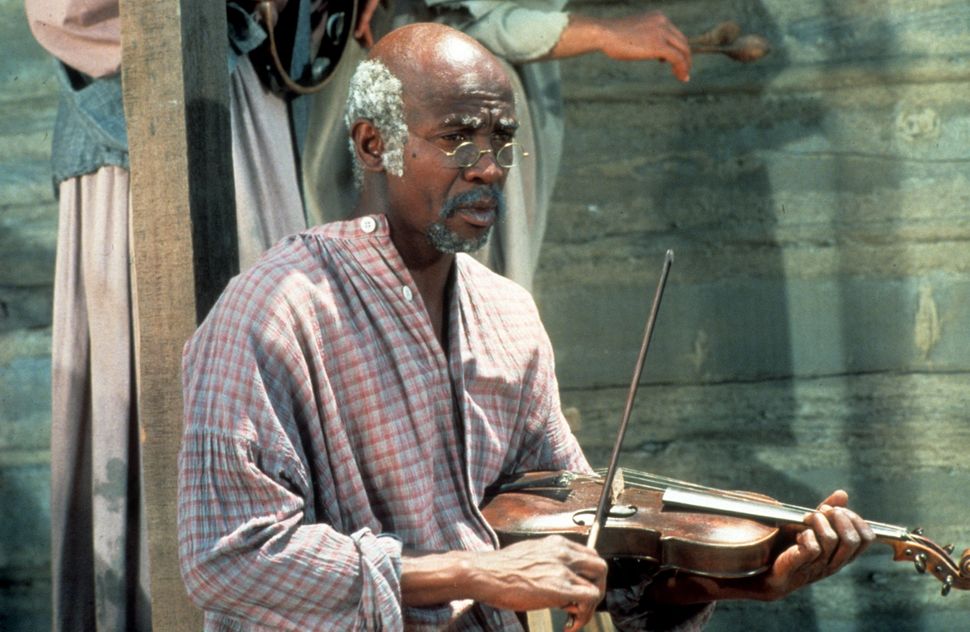

What, then, accounts for the relatively fallow period that left Gossett taking B- and C-level projects in the 1990s and 2000s? Why didn’t the stage veteran, who became famous playing Fiddler in “Roots,” one of the 20th century’s most far-reaching cultural events, walk away with a career rivaling, say, Clint Eastwood?

There’s a story Gossett returns to often. He wrote about it in his 2010 memoir, “An Actor and a Gentleman.” When he retells it in interviews, he tends to use identical verbiage. It is clearly the inciting incident of his adult life, the key that unlocks the tension underlying how Gossett moves through the world.

A fitting precursor to the themes “Watchmen” would later address, the story goes like this: In the late 1960s, Gossett ventured to Los Angeles, where movie star dreams are made. With a number of Broadway and film credits to his name, including stage and screen productions of “A Raisin in the Sun,” he’d been summoned by high-powered agent Lou Wasserman. The civil rights movement was making inroads, and now he was being invited to Hollywood’s big-boy table. Gossett flew first-class. He was put up at the luxe Beverly Hills Hotel and lent a stylish hardtop convertible. Driving back to the hotel, Gossett threw on some Sam Cooke tunes, ready to soak in the California sun. He felt invincible. But what should have been a 20-minute trip lasted some four hours because cops stopped him so frequently.

“It was the largest rude awakening I’ve had in my life,” Gossett said. “I met every policeman. ‘Who do you think you are?’ ‘Put that top up.’ ‘Turn that music down.’ ‘Shut up.’ ‘Sit on the curb.’ I was not prepared for it.” Later that same night, he was outside the hotel when police officers handcuffed him to a tree for walking while Black. When that’s your introduction to Hollywood, you’re going to develop some complicated feelings about whether you belong.

Gossett had grown up in Brooklyn, surrounded by what he describes as an almost idyllic working-class multiculturalism. Race wasn’t much of a handicap for him, so he hadn’t thought to investigate the color of his skin. “At that particular time, I didn’t know much about my Blackness,” Gossett recalled. He attended New York University, befriending the Greenwich Village hippies who touted free love and spent their evenings watching Cass Elliot and Joan Baez perform in bars where everyone snapped their fingers instead of applauding. He wrote poems, one of which turned into “Handsome Johnny,” a Dylan-esque anti-war song that became a modest hit for Woodstock opener Richie Havens. (“That song kept me from being homeless,” Gossett said. “A landlord was putting me out when I got a residual check.”) He did Jean Genet’s “The Blacks” off Broadway and the musical “The Zulu and the Zayda” on Broadway. For him, the New York arts scene was a place of opportunity. Los Angeles, and by extension the mainstream movie business, was not.

In a way, those formative police encounters braced Gossett for what would follow, namely bouts of success bookended by struggles. The fame that accompanied “Roots,” whose 1977 finale remains one of the most-watched television episodes ever, led him to Studio 54, and Studio 54 led him to alcohol, freebase cocaine and the proverbial glitz meant to accompany stardom. When he won his Academy Award, he was only the third Black person to take home an acting Oscar. He certainly had the talent for an Eastwoodian rise, as well as the physique: They are both 6 foot 4.

“An Officer and a Gentleman” showcased Gossett’s ability to give the most ferocious disciplinarian an undercurrent of decency. One glance at his sly simper and attentive eyes, and you know there’s more to the character than the commands he barks. But the great opportunities that Oscar darlings are supposed to get didn’t arrive. His next big-screen gig was “Jaws 3-D.” Then came “Enemy Mine,” a Wolfgang Petersen spectacle in which thick alien makeup concealed his face, followed by more so-so studio projects that did little to boost his prestige (“Iron Eagle,” “The Principal,” “Toy Soldiers,” “Diggstown”). Many of his contemporaries were thriving while Gossett was making “Firewalker” (1986) and “The Punisher” (1989) opposite Chuck Norris and Dolph Lundgren, respectively — guys who aren’t exactly known as esteemed thespians. He reteamed with Lundgren for 1991’s “Cover Up,” which didn’t even get a theatrical release in the United States. Again Lundgren received top billing.

Gossett enjoyed some of those experiences, but there was a caveat that can’t have helped his sense of self-worth: “All of those men got more money than me and more attention,” he said. It wasn’t the first time he’d dealt with that. His agent told him to turn down “Ragtime” (1981) because he would have been paid “close to scale.”

Delroy Lindo recalls encountering him by chance in Australia when Gossett was making “The Punisher.”

“I remember thinking, ‘Well, what is Louis Gossett doing in a Dolph Lundgren film?’” Lindo said. “I don’t want to go down a rabbit hole right now, but I happen to think Louis Gossett is a great actor with a capital G — the difference being the opportunities that were afforded those men as compared to some of the other renowned actors one could name. So, wow. Dolph Lundgren, wow. That was not casting aspersions on Lou. It was, if anything, a comment about the industry.”

Gossett adopted a front that disguised his disappointment. In 1987, he claimed to a Toronto Star reporter that he “wouldn’t be getting $1 million per movie” without his Oscar, but even that was a facade.

“The truth is, I never made a million dollars for anything,” he told me.

Not much later, Gossett met with director Jonathan Demme about playing Hannibal Lecter in “The Silence of the Lambs,” the type of role he’d had “fantasies” about. (He says he also campaigned to play a Bond villain.) A hot property like “Lambs” could have launched Gossett’s artistic renaissance, but Demme was reportedly hesitant about potential backlash from casting a Black actor as a psychopathic cannibal. He hired Gossett’s friend Anthony Hopkins instead.

Gossett’s memory from that time is fuzzy. Was it the drugs? Is that why he wasn’t getting better roles? “I can’t tell you what I lost because of it,” he said, resigned but not dejected.

He went to rehab and kicked the addiction, at least for a while. The parts didn’t get much better, though. I could list them, but you wouldn’t know most of the titles unless you have a deep affinity for TV movies from the ’90s. Let’s just say the big ambitions turned into gratitude to be working at all, especially because he wasn’t interested in the celebrity PR game. To stay artistically nourished, he did theater on the side.

In 2004, Gossett went back to rehab. He came out renewed, and it shows. As he recounted his past, there wasn’t a hint of bitterness in his voice, not even about the police officers who’d racially profiled him.

“He radiates joy,” Damon Lindelof said. “You’re like, ‘No one can be this optimistic. No one can be this generous.’”

After getting involved with the Congressional Black Caucus, attending Barack Obama’s presidential inauguration with Cicely Tyson, and founding a nonprofit organization called the Eracism Foundation, the actor is now focused on spiritual fulfillment.

“I learned how to get rid of resentment and go back to the basics of enjoying a life,” Gossett said.

Regina King’s first real conversation with Gossett happened when they had dinner together in Atlanta right before the “Watchmen” shoot began. During the course of the series, Angela, the steely Oklahoma detective whom King portrays, discovers that Gossett’s character, Will — a mysterious figure in a wheelchair who shows up to coax a white supremacist (Dan Johnson) into lynching himself — is her grandfather. In the season’s most powerful episode, Angela lives out Will’s painful racial memories, which have been harvested in pill form. King wasn’t conscious of it at the time, but she now realizes that listening to Gossett’s stories over dinner informed her performance on an almost molecular level.

“We had several conversations just about Lou’s history, his life on this place called Earth, and his relationship to his grandmother,” King said. “I think being there was bringing a lot of stuff up for him. I feel like having the opportunity to be a person that listens and not talks, and allowing him to pour into me all of his life experiences as a young man, was probably a lot of subconscious preparation for that. Sometimes the universe creates moments for you to be a vessel that prepares you for something to come. This is kind of a discovery right now that you asked me that question. I believe that that’s what that did for me. It helped my body language.”

In “Watchmen,” Gossett speaks with a gravel that conveys both fatigue and foresight, someone who has seen it all and lived to tell the tale. For an actor in his 80s, art and life can sometimes intermingle. At the time, he was battling lingering respiratory issues caused by a toxic mold that spread through his Malibu, California, home, and the night shoots were grueling. Not only did Gossett not complain, according to Lindelof, but he surprised the show’s producers with his performance in the pilot. It was more “playful” than they’d anticipated, and so the writers incorporated that lightness into subsequent scripts.

“We always referred to ‘Watchmen’ as a ‘century show,’” Lindelof explained. “It takes place over the course of 100 years, so we wanted an actor who the audience already had a century’s relationship with — someone whose career basically spanned all this time, and someone who also wore the weight of that on his shoulders.”

The series, combined with the Black Lives Matter uprising that has transpired this summer, has furthered Gossett’s own feelings of hope. When he was making “Boardwalk Empire” in 2013, he asked to tweak a line to better reflect Black vernacular, but the producers apparently told him to say it the way it was written. Now, he feels a “mutual respect” on sets that didn’t always exist before. He wants to work with Oprah Winfrey, Ava DuVernay and Spike Lee, the latter of whom offered Gossett a small role in 2015’s “Chi-Raq.” He wants to help younger Black artists know that they don’t have to submit to the showbiz promotional machine to achieve greatness. He wants to be a force for good, a role model for his two children. Maybe in his final years, the industry will respond in kind.

“I’m very fortunate to not have an ego,” Gossett said. “That goes in the garbage with the drugs. I have friends and family, some people to love and people to love me. It’s beautiful here. It’s beautiful, this place.”

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link