[ad_1]

When Amanda Reyes thinks back on how she was radicalized, it probably started with the IUD. In 2008, at 20 years old, Reyes was studying humanities at the University of Alabama and working part time at the campus Starbucks. Reyes, who was in a long-term relationship, needed a reliable form of birth control. After researching online, she decided on the Mirena, an IUD that can prevent pregnancy for up to seven years. It was pricey, though, so for three months she ate only peanut butter sandwiches and ramen noodles to save up.

When it came time for her appointment at the university medical center, things did not go to plan. The male doctor, Reyes recalled, was reluctant to do the procedure. What if her boyfriend wanted her to get pregnant sooner? he asked. He left her in the examination room for hours, claiming problems with her insurance, Reyes said, and then he took off for the day without letting her know.

Reyes did not get her IUD. The university medical center did not immediately respond to HuffPost’s request for comment.

The experience was a wake-up call, she told me over a Zoom call last month.

“This guy – who had no idea what my life was like outside that room – was making decisions for me based on what he thought was best,” Reyes said. “It was ridiculous.”

These days, Reyes works to ensure that other people are guaranteed the agency that she was denied as a college student. She runs the Yellowhammer Fund, an Alabama-based reproductive justice organization that envisions “a society in which individuals and communities have autonomy in making healthy choices regarding their bodies and their futures.” The fund, which helps people obtain abortions, burst onto the national stage in 2019 after Alabama enacted the most extreme abortion ban in the country.

Although a judge blocked the law before it could go into effect, people who were outraged by the ban and looking for a concrete way to get involved flooded the relatively unknown nonprofit with donations. Within two weeks, the fund’s bank account swelled from a few thousand dollars to $2 million.

All of a sudden, the scrappy nonprofit had the money to dream big. And it did.

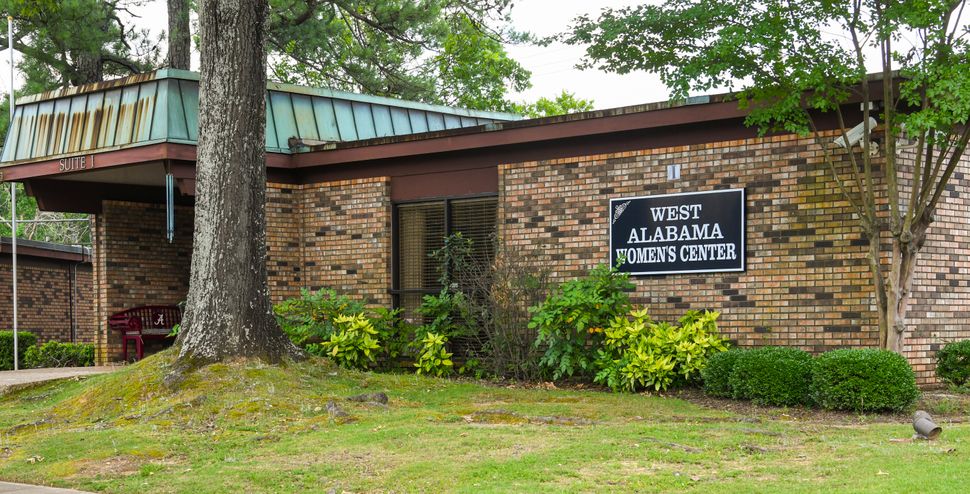

On May 15, exactly one year after the abortion ban was signed into law, the Yellowhammer fund purchased the West Alabama Women’s Center, an abortion clinic that provides about half of the abortions in the state. As long as abortion remained legal, people would have a guaranteed place to get one, Reyes said. On Aug. 1, she took on the role of clinic director. At 32, she is among the youngest administrators of an abortion clinic in the country.

Reyes is part of a new generation of activists fighting to enshrine reproductive rights in their communities. Their work comes at a time of heightened attacks from anti-abortion extremists who believe the time is ripe to overturn Roe v. Wade, the landmark Supreme Court ruling that legalized abortion nationwide. Still, crusaders like Reyes think it is a mistake to focus their efforts solely on abortion. True reproductive freedom, they say, requires an intersectional approach.

The Makings Of An Activist

Reyes, who is Latina, was born in a tiny town in Texas to teenage parents. She has thought at length about how her mother could have had an abortion if she wanted — it was the ’80s and abortion was fairly available in the area — but had decided to raise her instead.

“My mom’s experience really informs my perspective,” Reyes said. “You should have the choice to do whatever it is that you want to do, and you should be supported in that choice.”

When Reyes went off to college in Alabama, she was introduced to the concept of reproductive justice in a class taught by Brittney Cooper, an author and expert in Black feminist thought. Coined in the 1990s by a group of Black women, the term “reproductive justice” refers to an intersectional framework that positions reproductive rights within social, political and economic contexts. While the mainstream reproductive rights movement focused on a woman’s right to choose, reproductive justice proponents argued that for many marginalized people without the money or resources to access abortion, there was no real choice at all.

Reyes learned this firsthand after she began volunteering as a clinic escort at the West Alabama Women’s Center, an abortion clinic in Tuscaloosa. There, she met women who were turned away because they were too far along — they hadn’t had the means to make it to the clinic earlier. She also saw people who would have gone through with their pregnancies if only they could have afforded to raise kids.

In 2016, with the election of President Donald Trump, Reyes decided she wanted to do more. She founded the Yellowhammer Fund, a nonprofit that helps people overcome the logistical and financial barriers keeping them from getting abortions. It also functions as a reproductive justice organization, offering assistance to pregnant people in whatever form they need.

“We want to make sure that people can get abortion care when they need it,” Reyes said. “But we also recognize that a lot of these people would be making different choices if they had more resources available to them.”

Shot Into The Spotlight

In May 2019, Alabama’s Republican governor, Kay Ivey, signed the Human Life Protection Act into law. It banned abortion in nearly all cases and threatened doctors who performed the procedure with felony charges and up to 99 years in prison.

The legislation was temporarily blocked by a judge, but not before it triggered mass outrage across the country. For people yearning to take action, donating to the Yellowhammer Fund emerged as a viable option. By the end of the year, the group had amassed $3.35 million.

Like many nonprofits newly flooded with cash, the organization soon came under scrutiny for how it was managing its money. In 2019, the group provided more than $250,000 to fund nearly 1,100 abortions in Alabama. But it also used money to invest in other services, such as breastfeeding support and birth doulas.

To her detractors, Reyes counters that her organization never hid its intentions to expand beyond basic abortion funding.

“Because we were such a small organization, people were so willing to believe that we either had no idea what we were doing or that we were taking advantage of people and doing whatever with the money,” she said.

Jenise Fountain, an activist in Birmingham who offers practical support to Black mothers living in poverty, recalled getting an unexpected call from Reyes in 2019 saying the Yellowhammer Fund was donating $10,000 to assist her work.

At the time, Fountain was running a backpack drive, stocking school backpacks with supplies for children in need. She had never heard of the Yellowhammer Fund.

“One thing Amanda does extremely well is to be intersectional,” Fountain said during a phone call with me. “She’s funding full-spectrum reproductive justice — and that includes if you have a child already.”

Fountain said she admired Reyes’ dedication to learning from activists who are on the ground working with vulnerable communities.

“Since we’ve been in contact, she’s always asking, ‘What do you need to address the issues in your area? What are your moms’ needs? What can I do to help?’” Fountain said. “She listens.”

Reyes has also worked to bring the perspectives of trans and nonbinary people into Yellowhammer Fund’s work.

“She was like, y’all come to the table,” said TC Caldwell, a trans activist working with TKO Society, a nonprofit that provides essential support services for LGBTQ people living in Alabama. “Because our voices had been erased for so long, she made sure there was room not only for TKO Society, but for people like me.”

The Yellowhammer Fund donated condoms and emergency contraception to the TKO Society so that they could give it to their clients for free, Caldwell added.

“You don’t really realize the need until you offer it,” they said. “Amanda understands reproductive justice is more than just access to abortion — it’s holistic.”

In May of this year, the Yellowhammer Fund revealed its big-picture plans for abortion access in the state when it purchased the West Alabama Women’s Center. For Reyes, it was a type of homecoming. It was the same abortion clinic she had volunteered at as a college student.

Running The Clinic

When I last spoke to Reyes, she was at the West Alabama Women’s Center, working in her office. As a woman in her early 30s, Reyes is somewhat of an anomaly in the abortion world — the industry is dominated by aging activists who got into the reproductive rights movement decades ago and never left.

“There hasn’t been a pipeline of mentorship that has allowed many people under 50 to take on these roles,” Reyes said. “This is a problem with our movement and who we consider ‘the right people’ to take on leadership roles, but also a problem with access to money.” Young people often don’t have access to the network of donors and investors needed to take on the financial risks that come with running an abortion clinic, she added.

Gloria Gray, the previous owner of the West Alabama Women’s Center, had long wanted to retire but struggled to find the right buyer. Then came the Yellowhammer Fund.

“We had the opportunity. We had the resources,” Reyes said. “And what better way is there to improve abortion access in the state than to actually have a hand in providing those abortions?”

Owning and operating an abortion clinic is exceedingly difficult work, especially in states that are hostile toward reproductive rights. Clinic staff must battle anti-abortion protesters, state efforts to restrict access to abortion, constant litigation and stigma from within the community. It can also be dangerous. Violence at abortion clinics is on the rise, according to a report by the National Abortion Federation, a professional association of abortion providers. In 2019, members of NAF reported an increase in intimidation tactics, invasions and other activities aimed at disrupting services.

The Very Rev. Katherine Ragsdale, who serves as president and CEO of NAF, said she was excited for Reyes to take a leadership position.

“Having young people moving into ownership and administration is a great thing to see for those of us who hope someday to be able to retire,” she said.

Reyes was already getting a sense for how hard it was going to be as administrator by the time we spoke. The coronavirus was sweeping the state, and at her clinic, anti-abortion protesters amassed outside, not wearing face masks and violating social distancing guidelines.

She described how protesters were filming her staff performing health safety protocols with patients before they entered the clinic. Anti-abortion activists regularly gathered evidence they believed could be used against the clinic and filed complaints with the state, Reyes said. She knew that the pandemic gave them ammunition, and she was doing everything she could to ensure the clinic would remain open.

Because of the constant scrutiny, “we have to have a better and stricter protocol than anyone else,” she said. “But that means we see less people, and it’s even more difficult to get an abortion.”

Reyes has ambitious plans for the future of the clinic. She also has help.

In August, the West Alabama Women’s Center announced that it had a new medical director: Leah Torres, an OB-GYN who is unapologetic about her abortion activism. Torres will replace Dr. Louis Payne, who is in his 80s. With Torres at the helm, the clinic will introduce full-spectrum reproductive and sexual health services, including well-person exams, contraceptives, STI testing, prenatal care and trans health services, the clinic said in a press release.

Reyes’ vision of creating a comprehensive reproductive health care center is finally coming into fruition.

“I want to make the clinic even more patient-focused right than it already is,” she said. “We can build toward providing empowering health care to people.”

CORRECTION: A previous version of this article mischaracterized Mirena as a “copper IUD.” It is plastic and contains hormones.

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link