[ad_1]

DURANT, MISSISSIPPI ― Justice Grisby, like every other student in Holmes County School District, knew about the paddle. Long, smooth and wooden, it was kept locked away in the principal’s office, except for the occasions it was taken out and used as a weapon of punishment. Grisby, a recent high school graduate, was lucky to survive her K-12 experience without ever getting paddled, but she will never forget the time she saw it happen to someone else.

Grisby, who is Black, was in the sixth grade. It was 2014 and her class was working on a reading project. As usual, the class bully was acting out. The girl was grabbing another student’s poster board when a school administrator walked through the classroom and caught the misbehavior.

Paddlings were supposed to occur in the main office, behind closed doors. This time, it happened in front of a class of around 30 rowdy kids. The student was made to stoop over and the administrator wound up his arms, and struck her behind twice with his wooden paddle, Grisby recalled in an interview with HuffPost. The class broke out in jeers and laughter.

“You know how when you’re hurt and you laugh so people won’t see you cry?” Grisby asked, explaining the situation. “She kind of laughed, but I think she wanted to cry.”

Most states ban corporal punishment in schools. But Grisby lives in Mississippi, a state that not only allows it, but has the highest rate of the practice in the country.

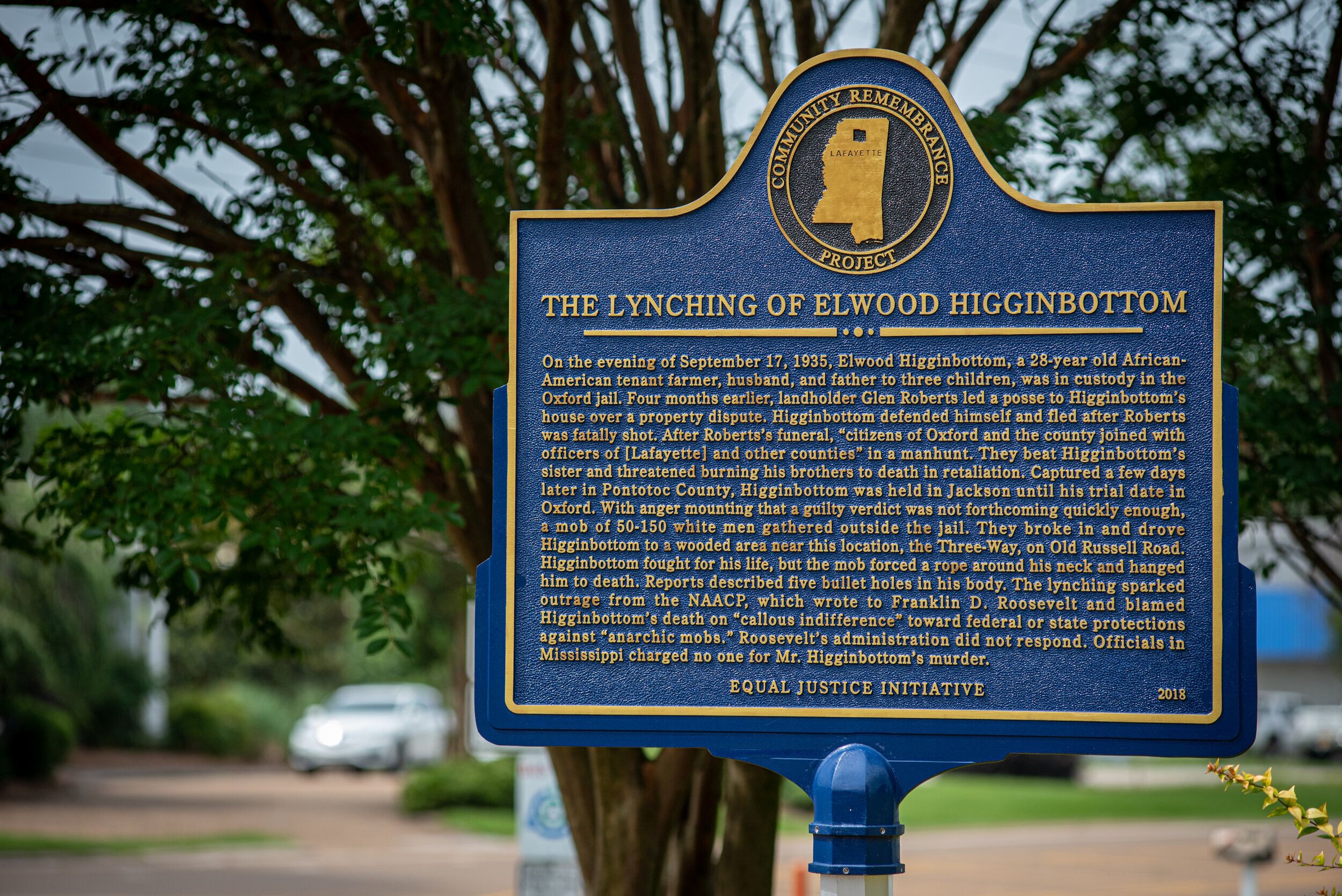

For almost a century, Mississippi was one of the nation’s leaders in another category of punishment: lynching.

Between 1865 and 1950, at least 708 confirmed lynchings took place in the state; the vast majority of victims were Black, according to prior research by professors E. M. Beck and Stewart Tolnay. They included Black teenagers falsely accused of crimes; Black men accused of offenses as minor as “insulting a white woman”; and Black women who were shot simply because of “race hatred.” Often, white mobs tortured victims, while others cheered and took photographs, later published in newspapers across the country.

Now, a new study makes a compelling case that these two acts of violence are related. Places with historically high rates of lynching over a century ago are now more likely to paddle students today, particularly Black students, according to the study, provided to HuffPost.

The history of state-sanctioned violence against Black people in Mississippi is as old as the state itself. Before the Civil War, the state had one of the highest concentrations of enslaved peoples in the country. And well into the civil rights era, white supremacists assaulted, terrorized and killed organizers for racial justice. Hundreds of years later, state- and school-sanctioned brutality against Black people is baked into the fabric of the community.

As millions of Americans protest police violence and racism against Black people after the killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, the study’s findings are especially urgent, connecting racial violence in the past with brutality against Black people today.

“Even though we’re not studying policing, we’re still looking at physical punishment of Black bodies,” said Aaron Kupchik, professor of sociology and criminal justice at the University of Delaware and study co-author. “The situation Black students find themselves in today doesn’t come out of nowhere.”

The idea for the study came out of discussions between Kupchik, who studies racial inequality in school punishment, and Geoff Ward, a professor of African and African-American Studies at Washington University St. Louis, who studies histories and legacies of racialized violence. Nick Petersen, assistant professor at the University of Miami, helped to lead data analysis as he and Ward had recently published a similar study of lynching and contemporary homicide. James Pratt, Ph.D. Candidate at University of California, Irvine and adjunct professor at Albany State University, and one of Ward’s graduate students at the time, also assisted in the research.

While school corporal punishment is only allowed in 19 states and rarely used in most of them, there are pockets where the practice continues to thrive. Researchers sought to uncover if those places were marked by high rates of historic racial violence. They asked: How much of what students, particularly Black students, face today is a result of what was written yesterday?

To answer this question, researchers took data on the frequency of school corporal punishment in 10 Southern states, self-reported by schools and collected by the U.S. Department of Education, and compared it with a database of historic lynchings. The results indicated a clear relationship.

Though overall rates of corporal punishment are higher in places where Evangelical Protestantism is popular and where rates of educational attainment are lower, researchers discovered that corporal punishment is more common in areas with histories of lynching for all students. But they also discovered that this effect is especially pronounced for Black children.

Nearly 90% of districts in Alabama, Arkansas and Mississippi reported at least one school using corporal punishment during the 2011-2012 school year. Black students were at much higher risk for this punishment, despite committing a smaller share of “serious student misconduct,” says previous research cited in the study. Each additional historic lynching in a state’s county, the study found, increased the odds corporal punishment happening to a Black student by about 6%. These odds also increased about 4% for white students.

“School punishment, in this case corporal punishment, doesn’t arise out of nowhere. There’s a historical trajectory,” said Kupchik. “Though this happened 100 years ago, the rates of racial violence are predictive of how we punish Black students today.”

The researchers connect corporal punishment to the whipping of enslaved Black Americans and to mass mob lynchings designed to hurt individuals and instill terror in entire communities. These past terrors, they argue, are tied to what some kids experience in schools today in between math and gym class. White school officials, living in communities with a historic acceptance of racialized violence, may be more likely to dole out corporal punishment on Black students because of implicit or explicit biases, posits the study.

“We suspect that schools in counties with more pronounced histories of violent racialized social control, where physical pain has long been used to discipline and punish marginalized populations, are more likely to employ corporal punishment, and disproportionately impose this punishment on Black students today,” says the study.

But Black families and officials may be more likely to support this type of punishment against students, too. In places where Black bodies were regularly terrorized, communicating the physical cost of misdeeds could feel particularly urgent to Black adults, who may feel the need to convey the seriousness with which the outside world will treat Black children.

“It is well established that black population support for corporal punishment is rooted in concerns for survival in a hostile social environment,” the study notes.

Indeed, for students like Grisby, this past has everything to do with the present.

Where Grisby lives, in Holmes County, Mississippi, there were 13 lynching incidents between 1865 and 1950, per the lynching database used in the study, meaning students there have considerably higher odds of facing corporal punishment compared to students in places with fewer or no known lynchings. Indeed, in 2015, Holmes County School District administrators paddled 281 students throughout the school year. Nearby, in Carroll County school district, 89 students faced the same fate that year.

Holmes county finally banned corporal punishment in 2018, after years of lobbying from the Nollie Jenkins Family Center, a local youth development group with which Grisby is involved. It was a long, uphill battle that involved years of campaigning to change the minds of parents and teachers who viewed the practice as a necessity.

Grisby had to work on deprogramming her instincts, too. For her, this type of punishment in a school setting doesn’t even seem abnormal. For most of her life, she considered it a natural feature of life in her community. Sometimes, Grisby even wonders if some of her peers deserved what they got, until she thinks about it more deeply.

“I wouldn’t want anyone to do that to my brother or sister. You shouldn’t hit somebody with wood,” she said on the practice of paddling, in between pauses to work out her thoughts.

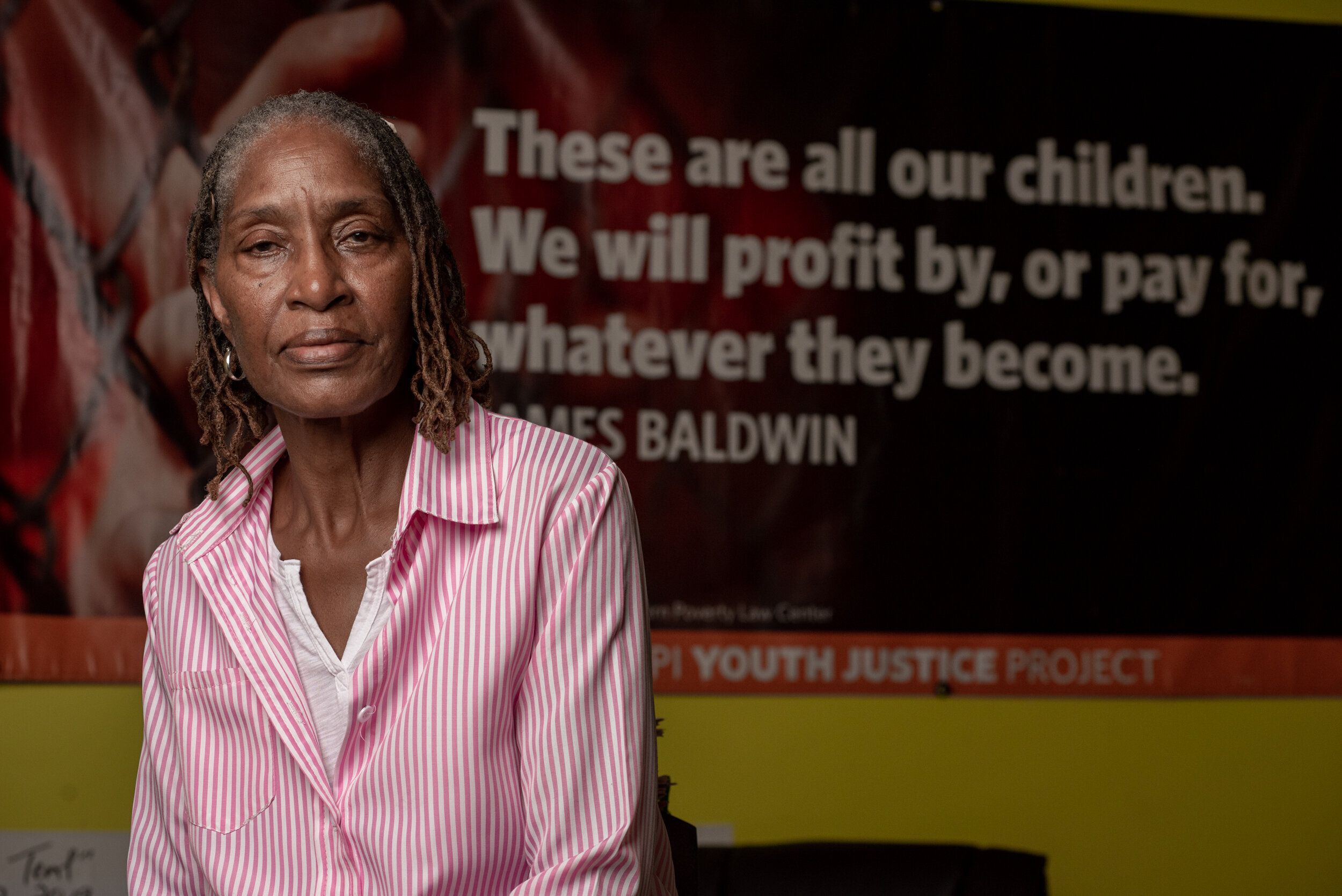

Ellen Reddy, 66, remembers a time when almost everybody in the Holmes County School District ― from teachers to bus drivers ― used physical violence against children. A rule, instituted about 10 years ago, that only school leadership or a “designee” appointed by school leadership could paddle students constituted initial progress against the practice. Now, thanks in part to her work, school corporal punishment is now outlawed here, at least on paper. As leader of the Nollie Jenkins Family Center, a youth development program for African American children in Mississippi that she co-founded with her twin sister, Reddy has dedicated much of the last 25 years to this and other causes.

“It is a mindset ― spare the rod, spoil the child,” said Reddy while prepping platters of tuna salad and hot dogs before a 2019 seminar for local kids. There’s an idea that, “If you don’t spank your child you’re not a good parent.”

Reddy recalled advocating years ago for one child, in sixth grade at the time, who was paddled so badly by a school administrator that one of his buttocks swelled to twice the size of the other. She recounts hearing that this child never finished high school.

“I cried many a times leaving school board meetings, prosecutor’s office, sheriff’s department, but I just have to pull over and say, I have to cry this out,” Reddy said, describing the many kids for whom she’s advocated over the years, sometimes only to be met with callous indifference.

Now, the policy has changed but Reddy is skeptical that the practice has fully gone away, speculating about children facing pinches and slaps upside the head and rulers. Both Grisby and Reddy say they’ve heard that in lieu of corporal punishment, suspension rates have increased, meaning that one problem has only been replaced by another. (James Henderson, Holmes County superintendent, told HuffPost that suspension rates have actually decreased.) Reddy keeps her ear to the ground, prodding students about how school has changed and what issues she should be on the lookout for.

Throughout her campaign, Reddy has faced opposition from leaders of all colors and affiliations. So she comes armed with research; professional organizations like the American Psychological Association and American Academy of Pediatrics oppose corporal punishment, citing studies that show it only leads to more aggressive behavior, while putting a child at increased risk of mental health disorders. But some families can’t imagine a world in which children will behave without physical consequences looming.

“It’s the culture. Not necessarily the Black culture, but the culture of where we are, the deep South. It’s part of the culture in which we have been oppressed,” Reddy said with a sigh. “We still have not gotten rid of beating our children and somehow thinking beating is going to make them better human beings.”

Henderson, the district superintendent, grew up in Holmes County and agrees with Reddy’s assessment, which is why he says he supported abolishing the practice when he started his job. He had his own traumatic experience with corporal punishment as a child. When he was a third grader, a teacher paddled him in front of his entire class, in an incident similar to the one Grisby described. While he sat in a chair and sobbed, the teacher struck his thighs 10 times.

“That public humiliation damaged me,” said Henderson. “I’m an adult and I’ve grown out of it, but every time I think about that incident, there was a feeling that came along with it.”

Further, in an epidemic of police violence against Black people, advocates like Reddy question how effective corporal punishment is in teaching Black children how to safely comport themselves around white outsiders. “The white community will still view [our kids] as criminals. Doesn’t matter how well behaved they are,” she said.

Graphics credit: Manyu Jiang

In the past year, Reddy’s organization, the Nollie Jenkins Family Center, has been working to extend a school corporal punishment ban outside of Holmes County through all of Mississippi.

At a 2019 seminar at the center’s headquarters attended by HuffPost, located in a house in a remote Mississippi town, Reddy prepped a group of about 20 middle and high school girls to take their fight to the Mississippi legislature. She spoke to the teenagers amid a backdrop of posters with James Baldwin quotes and messages reminding students, “Mike Brown can’t vote. But I can.”

“Would you go with me to the capital and do the hard work? Would you testify before a committee? Would you be wiling to show them what it feel like when you administer corporal punishment?” Reddy asked triumphantly to cheers.

She questioned the group about how the possibility of facing corporal punishment in schools makes them feel. One mimicked what paddling looks like, bending over as if they’re waiting for an adult with a thick wooden paddle to enact a punishment.

“When it’s a man, I don’t feel like it’s right. My daddy is not gonna bend me down like this, so why do you do it?” said one female student.

Reddy asked the group if they would feel any less vulnerable if it were a female administrator performing the paddling.

“Either way you’re still bending, and there’s no telling what they could be doing back there,” offered Grisby, who will be studying criminal justice at Jackson State University next year.

These are unfortunately considerations Grisby had to think about. Her K-12 experience was characterized by a culture of violence against students ― even more than just sanctioned corporal punishment.

She recalled, in middle school, a boy getting choked by an administrator because he wouldn’t give up his phone.

When Grisby was in eighth grade, a teacher, who was white, choked her, too, she said.

Grisby hadn’t done anything to set the teacher off, at least not anything remotely worthy of punishment. He accused her of having left a coat in his classroom; Grisby said the coat wasn’t hers. When he continued to press her on it, she started to walk away. That’s when he came up from behind her in the hallway and put her in a chokehold, his arm squeezing firmly around her neck. Another teacher intervened right as her vision started to get fuzzy. Her mom complained to school leaders, but Grisby doesn’t recall anything changing as a result.

“You know how that goes, they’re going to take the teacher’s word,” she said.

She became afraid of going to his class ― he taught social studies. That was when Grisby, a straight-A student, got her first F.

“I feel like he didn’t like people of our color,” Grisby said of the white teacher. “He used to always tell us he was gonna send us back where we came from.”

“I probably put him in a mindset of like, back then and stuff.”

Henderson, who said he is unfamiliar with these allegations, wasn’t superintendent at the time. Since then, he noted, the district has undergone a consolidation process that involved substantial turnover. “Fortunately, these things are no longer happening since I have been the superintendent,” he said.

In the past few months, Reddy’s recent efforts have started to pay off.

A bill was introduced this session that would ban all forms of the practice in school. But during the coronavirus pandemic, it lost political momentum in the Republican-controlled legislature. (In 2019, Mississippi passed a law banning corporal punishment in schools for students with disabilities.)

Faith-based groups, school board members and some parents have been pushing against Reddy’s efforts, though she’s been working to convince them that school will continue as normal if the practice is replaced with peer mediation, peace circles and increased investments in school counselors. Such changes, though, take work and resources, and she’s found that many people prefer the status quo if the alternative requires effort and money.

After graduating this spring, Grisby has been working full time at a Baskin Robbins while preparing to go to college. She plans to study criminal justice and has dreams of becoming a judge, eventually working her way up to serve the nation’s highest courts. She’s been watching the racial justice protests roil the nation from the sidelines.

She has mixed feelings, though, about Black Lives Matter and worries that it sends an exclusionary message to other groups. Reddy, though, watching from afar, said the movement’s efforts have been inspiring, confirming that now is the right time to move on this work.

Corporal punishment “is a practice that grows out to being enslaved … the methods, the policies, just changed but we’re still being oppressed, the knee is still on our neck,” Reddy said.

Kupchik has also been watching and meditating on how what’s happening today is a result of hundreds of years of policy. He believes he and his co-author’s research proves a simple fact: none of this is accidental.

“It’s not just about individuals in this case, principals or teachers or people being mean. It’s not about bad apples,” said Kupchik. “It’s about a legacy. A historic legacy of racial violence.”

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link