[ad_1]

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Tina Barney, Sarah Hermanson Meister, Liz Deschenes, Sofia Borges, and Sam Contis.

JULIENNE SCHAER

“One of the great things about working for 40 years and being 190 years old is you get to see history,” the photographer Tina Barney, who is 72 years old, told a rapt audience last week. She paused for a bit, then continued, “You see so much in 40 years, and yet not much has happened at all.”

Barney was referring to the size of her colorful photographs, which, back in their day, were printed at large sizes rarely seen in the art world, but it was a statement that also could’ve applied to the whole of the panel at which she was speaking: “History/Her Stories: Photographs by Women” at the AIPAD Photography Show in New York, a talk about how female photographers can grapple with—and change—history through their work. Her fellow panelists—Sofia Borges, Sam Contis, LaToya Ruby Frazier, and Liz Deschenes, as well as Museum of Modern Art photography curator Sarah Herman Meister—were more optimistic that women photographers have come a long way. All of them seemed to agree on one point: being a woman in a field dominated by men isn’t easy.

Frazier kicked off the talk by discussing her black-and-white photographs of Flint, Michigan, where a crisis caused by a polluted water supply continues to impact the everyday lives of its citizens. (These semi-journalistic works, made in the tradition of Gordon Parks and Lisette Model, were recently on view at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise in Harlem.) She asked the audience how many people were aware that the crisis was still ongoing, and most people raised their hands. “I’m glad to see that,” she said. But how many knew that it wasn’t expected to be fixed until 2020? Almost no hands went up. “I believe my photographs are a platform [not only] for social justice, but also for equity,” she said, adding that she hopes her work, which has been published in Elle and the Atlantic, will illuminate what Flint residents are dealing with. “Photography,” she said, “has the power to change the way we think.”

Contis, whose pictures of an all-male school in California are currently included in MoMA’s “New Photography” show, agreed that taking pictures can be a way to bring the public’s attention to rarely seen subjects. Like Frazier, she’s working in a tradition dominated mainly by men. “We know Carlton Watkins, Ansel Adams, Edward Weston,” Contis said. All of them have, like her, traveled to the American West and photographed what they saw. But, she said, regretfully, “there aren’t many women in [this] environment.” Her images of students performing the role of cowboys—putting on hats, trying to understand their masculinity—is one way of “looking backward and forward at the same time.”

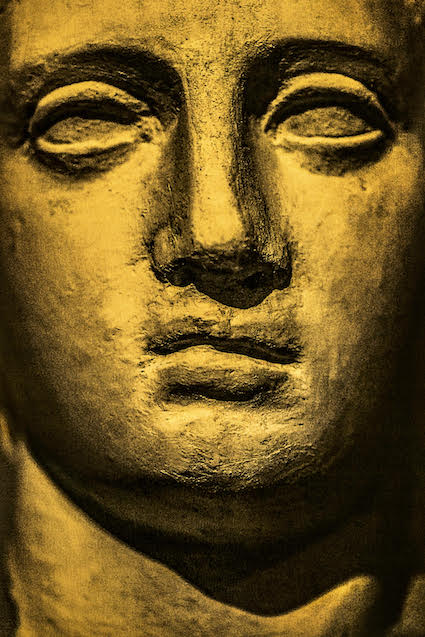

Sofia Borges, Yellow Chalk, 2017, pigmented inkjet print.

©2018 SOFIA BORGES/MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK, FUND FOR THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

Alongside Contis’s photographs at MoMA are Borges’s more conceptual ones, which deal with the nature of images. “What is reality?” Borges asked the audience, rhetorically, noting that she “never really understood the connection between meaning and depiction.” In an attempt to better understand the connection, Borges, like Contis, has looked to history. She described a visit to the caves in Chauvet, France, where millennia-old paintings of animals rush along the walls. The paintings made her cry, she said, because she knew that she and the artists who made them were both engaged in the same quest: to find out how pictures can seem like reality, if presented in a certain way.

Deschenes, in contrast, makes photographs that rarely resemble photographs—they oftentimes look more like abstract sculptures or installations—but her work is also deeply informed by history. “My work doesn’t reproduce very well,” she said with a laugh, as she explained how her work is in dialogue with Minimalist sculpture, early photography, and various other art forms. She teaches a class about women photographers at Bennington College in Vermont. “It concludes that we need to teach women in photography,” she said, “because it’s not taught.”

Almost everyone had by this point taken the opportunity to “geek out” (Frazier’s words) over Barney, who accepted the praise with an admirable air of cool. As Barney spoke about her color photographs of middle-class families across the United States and commissions for various magazines, she had to admit to having “never, for one second, thought of myself as a woman photographer,” or not at first, anyway. “I really went against the idea of being in a show of only women.” But now she said she sees a place for these kinds of exhibitions, and is actually fairly amenable to them.

This caused one audience member to ask a difficult question: What’s the difference between photography by women and photography by men? There was a long pause, and Meister asked Frazier to say something. “I had to be the one,” Frazier said wryly, continuing, “It’s important to resist these kinds of binaries and categories.” Deschenes concurred, saying that maybe, if there is a difference between male and female photographers, it’s in the way their works is received by critics. Barney also said that there is “no difference” between photographers of either gender. “I think my photographs look ‘feminine,’ just because of the color,” she said. She argued that her work does more than please the eye, though, and added quickly, “I just don’t think it should be narrowed down like that.”

[ad_2]

Source link