[ad_1]

On Saturday, June 6, a sea of mourners dressed in white gathered outside Cass Corridor Commons in Detroit. In a call-and-response with a gospel-inflected cadence we chanted: “We believe that we will win!” The Cass Commons, a center of nonprofit grassroots organizing in the city, was the final stop on a two-and-a-half-mile-long route, which began at the Underground Railroad’s Canadian terminus. Like the “Detroit Will Breathe” daily demonstrations against police brutality and anti-Black racism happening simultaneously blocks ahead, the memorial was spurred by the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. But this was a healing ceremony rather than a protest. Drawing lessons from the past, the procession stopped from time to time for impassioned teach-ins by Black elders. Two of the presenters, Bryce Detroit (the pseudonym of Bryce Anderson-Small), a record producer, performing artist, and community organizer, and Piper Carter, photographer and cultural organizer, are key figures of “entertainment justice”—a term Bryce Detroit coined to describe a burgeoning approach to music that aspires to move its audiences to act for environmental and racial justice.

Demonstrators and mourners alike demanded access to clean water and air for all. Protesters chanted “I can’t breathe,” echoing the pleas for life of Eric Garner, Eric Harris, George Floyd, and others. Days after local police shot tear gas at protesters, and amid a respiratory disease that disproportionately affects Black people, these words took on new resonance. At the memorial, Monica Lewis-Patrick, president and CEO of civil rights organization We the People of Detroit, cited 171,000 water shutoffs over individual payment issues by Detroit’s Water and Sewerage Department since 2014, grounding the dual pandemics of racism and COVID-19 in long-term patterns of state-sanctioned violence. Following a land blessing for Waawiiyatanong (the pre-colonial Anishinaabe name for Detroit), Bryce Detroit initiated a somber chorus: “In Detroit people can die of thirst.” Surrounded by musical instruments, glass vessels, and fruits, he reminded those present that while the protests started at the police precinct, the memorial began at the Detroit River because it is a real source of power: water, which gives and sustains all life.

Some present that sunny afternoon were part of a water-rights coalition that pressured Governor Gretchen Whitmer to reverse existing water shutoffs and put a moratorium on disconnections in the early weeks of the COVID-19 shutdown.1 In the wake of Detroit’s bankruptcy and suspension of democratic decision-making under emergency management, costs of water for residents increased dramatically. Many believe shutoffs for nonpayment are another tactic to force existing populations out of the city to make room for redevelopment. Detroit has been widely touted by outsiders as a destination for artists due to its affordability and excess space. This fetishization of the city as a bohemian refuge still proliferates via ruin porn featuring gutted factories and boarded-up houses covered in graffiti. These images gloss over the families who have made Detroit their home for generations. After Detroit’s wealth was decimated by deindustrialization and the collapse of the domestic auto industry, art has played a complicated role in the rebuilding the Motor City. The city’s population is nearly 80 percent Black and Dearborn, a city in the metropolitan area, has the highest percentage of Arab Americans in the US.2 Consequently, the local culture is rooted in labor, Black liberation, and immigration struggles. Techno and Motown were born here, so music has a particularly strong presence. Yet resources are directed not to Black and brown communities but to downtown, which has been rebuilt largely through incentives given to several white developers including Dan Gilbert, a major funder of the arts and co-founder of Quicken Loans, which has been criticized for predatory lending practices. In the absence of economic systems that provide for them, self-determined diasporic and colonized communities increasingly invest less energy in critique and focus on building their own infrastructures instead.

Photo Joe Gall

I first witnessed this as a resident at Red Bull Arts Detroit, where I brought my peripatetic exhibition on the politics of health, care, and disability, “Sick Time, Sleepy Time, Crip Time: Against Capitalism’s Temporal Bullying,” in the fall of 2019.3 For the closing event, I organized a conversation between Will See (the pseudonym of Owólabi William Copeland), a community organizer and emcee who positions his work in the realm of entertainment justice, and Wayne Curtis, an artist, urban farmer, and former Black Panther. See’s first album The Basics was named for the essential resources that every human needs to survive. The anthem “Take Tha House Back” (2013) explores the effects of mortgage and tax foreclosures in Detroit after the 2008 financial meltdown. The title becomes an infectious refrain over funk-inspired beats, interspersed with high-spirited rhymes that celebrate the movement for housing rights. The video for “Take Tha House Back” (2016) was produced by Bryce Detroit and directed by filmmaker Kate Levy, who grew up in a nearby suburb. Levy resists the tendency of white activists to focus on the bleak realities of poverty and racism, instead using her documentary skills to depict community strength amid exploitative socioeconomic systems.4 Her video cuts together images of extraction and resistance in a fast-paced montage. It starts with See lip-syncing to clips from a speech by anti-poverty activist Maureen Taylor. Then a white man scrolls through a land bank website where foreclosed properties can be purchased, and we see urban farms, families in living rooms, parties on stoops, and groups defending houses. Levy plays footage of Black residents moving out of homes in reverse, combining a recognition of forced displacement with a vision of people taking their houses back.

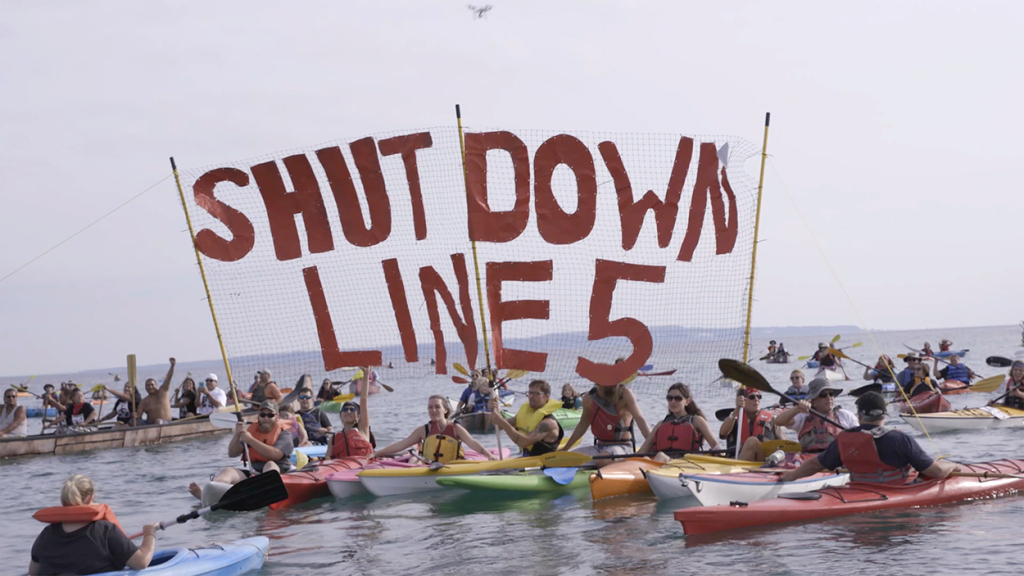

Levy’s video for another track from the same album, “Water Power,” collects solidarity shout-outs from Michigan to communities around the world fighting for access to clean water. The video’s structure balances voices of Michigan’s African diasporic and Indigenous communities to reflect their reciprocal respect for each other’s sovereignty. Amid footage of Michiganders protesting Enbridge’s Line 5 oil pipeline, an elder named Grandma Swooping Eagle shares her story of becoming extremely ill after the government air-dropped poison on her and others at Standing Rock. See brings a unique perspective to entertainment justice by examining chronic illness. “Day 2 Day Struggle,” also from The Basics, is about See’s ongoing struggles with kidney failure and the process of healing from lymphoma, heart failure, and other ailments. It opens by sampling The Notorious B.I.G.— “I know how it feels to wake up fucked up”—but See flips the lyrics by applying them to puking into pink plastic cups while wearing a hospital gown. A newer song, “This Aching Muscle” (2019), speaks to intergenerational trauma by linking the impact of pesticides on his ancestors who picked cotton to contemporary environmental racism: “Generational / Poppa got sprayed by the pest-icides as he was lined / In the field, fam and the rest, of cotton pickers / As they say, in Mississip, Goddamn n*****s / Or as they say in Flint, make ‘em sicker.” Over 2020, See is releasing Mutant Mixtape in phases, with tracks addressing disability’s relation to police brutality, gentrification, and intergenerational trauma through imagery rooted in comics and science fiction, with mutant superheroes working to stop supervillains like billionaire developers and their police lackeys.

See, who led an environmental nonprofit for years, increasingly anchors his music in emotional support work, mentoring people on spirituality, fatherhood, grief, and illness. He recently began partnering with the nonprofit Detroit Disability Power and with Healing by Choice, a collective comprised of women and gender nonconforming people of color, to host biweekly circles for givers and receivers of care. Originally held at a senior apartment complex but online since lockdown, the meetings incorporate therapies provided by healing practitioners, such as acupuncture and breathwork, into an intergenerational and cross-disability support group. Since the 1960s, the frameworks for understanding disability and chronic illness in the United States have been shifting from the single-issue approach of disability rights (largely led by white men with physical disabilities) to the intersectional, multisystemic approach of disability justice, which addresses economic, cultural, and social exclusion based on physical or cognitive difference (largely led by queer and trans people of color), to the newer movement toward healing justice, which embraces non-Western traditional medicines in response to trauma produced by colonialism and ableism. See emphasizes the complexity of embracing a disabled identity for those in his community. While numerous rappers—including J Dilla, Phife Dawg, and Heavy D—have died from complications related to chronic illnesses, they never laid claim to disability, due in part to mainstream hip-hop’s prevailing “tough-guy” archetypes.

While See carves out space for disability within entertainment justice, the movement’s charismatic progenitor, Bryce Detroit, views healing explicitly as a decolonizing process. Bryce Detroit previously worked as a brand manager in corporate music, which feeds consumerism through limiting tropes of Black identity. Entertainment justice takes the behavioral science tools used in marketing and applies them to promoting a new “Detroit Afrikan” identity that transcends oppression on the American continents over the last five centuries and focuses instead on tapping into ancestral roots. While See delivers poetic political analysis tied to his lived experience, Bryce Detroit prophesizes, crafting visions of a more just future, grounded in his quest for self-love and spiritual renewal in the present. Taking his cue from the entertainment industry, he designs his imagery and sound to appeal to emotion rather than to intellect, as political art tends to do. A good love song doesn’t just make you think about love, it propels you to make love. Entertainment justice aspires to pop music’s capacity for widespread distribution and high production values. A mash-up of musical traditions, drawing from the African continent and Detroit’s rockabilly, blues, gospel, soul, R&B, techno, and funk histories, it is sonically diverse.

When listening to Bryce Detroit’s verses, you believe it is possible to overcome what W.E.B. Du Bois called double consciousness—the duality experienced by Black Americans (and other oppressed groups) as they are “always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others” in a white racist society.5 On a crisp Saturday afternoon in February, Bryce Detroit hosted a “sonic brunch” for his new album, titled Structured Water, at Submerge, a venue housing the museum, record store, and headquarters of the historic techno label Underground Resistance. The name of the album refers to creative “flow” in hip-hop and how water can be “improperly structured” when polluted.6 During the intimate celebration, a team of collaborators augmented the album’s aural vibrations with visual, olfactory, and taste sensations. Vegan chef Nik Reneé Cole prepared dishes corresponding to the sonic influences of each track, for example, pairing collard green sushi with a song about prosperity. The brunch culminated in the screening of a video for “Rocked a Room” (2019), directed by Levy, which conveys the abundance that can occur in a specifically black space.7

The parable of two art worlds opens with Bryce Detroit playing a painter, making a self-portrait in his studio, before transitioning to his bleak white-cube gallery opening. The artworks on display, actually made by photographer Ricky Weaver, recall the strategy of empowerment in Kehinde Wiley‘s paintings of notable Black men in poses and settings reminiscent of the academic European portraiture that excluded them. Drab footage shows Bryce Detroit trapped at a seated gallery dinner with an all-white audience greedily chewing on animal carcasses. Bryce Detroit, taking from a platter of artichokes, rhymes: “Artichoke hearts / Art it chokes hearts / till content is D.O.A.” Then the action shifts to a separatist vision of a rich, colorful banquet with Black attendees dressed in white, wearing resplendent jewels and headdresses. They’re seated in front of a colorful mosaic by Olayami Dabls, founder of the Mbad African Bead Museum, known for creating cosmologies with cross-cultural significance in iron, rock, wood, and mirrors. After the screening, the brunch attendees spoke about their own contributions to the local creative economy. Bryce Detroit is currently working with Piper Carter, a supporter of women in hip-hop through her We Found Hip Hop organization, to renovate the historic Apex Bar, which featured performances by Al Green, Tina Turner, and George Clinton before the demise of Detroit’s auto industry.8 Controlling the means of production and distribution is essential to their vision of a new cultural infrastructure. It’s how they aim to revive the North End as a historical premiere music district, and make Apex a center for education, production, rehearsal, performance, and sales.9

© Pope.L/courtesy Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York. Photos Ron Amstutz.

JUST BEFORE NEW YORK issued its shelter-in-place order in March, I attended the closing of Pope.L’s exhibition “Choir” at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Entertainment justice adopts a rhetoric of Black empowerment similar to that of the Black Arts Movement in the ’70s. But, as critic Aria Dean writes, Pope.L has reacted to that position over the course of his life as an artist, developing a “hole theory” that posits Blackness’s relationship to trauma as a powerful creative force.10 The influential artist is perhaps best known for his crawl performances across the urban landscape, in which he turns his Black male body into an abject lightning rod. His 2002 traveling survey was titled “Friendliest Black Artist in America©”—a moniker he adopted with the understanding that Black masculinity is often synonymous with violence or threat. Pope.L catalyzes these forces of objectification to visualize and potentially reorder them. While entertainment justice takes an Afrofuturist approach uniquely rooted in a majority-Black city, Pope.L’s recent exhibition could be understood as an Afropessimist memorial in a museum.

Photo Ron Amstutz

“Choir” had three diffuse parts: Flint Water Meets the Mighty Hudson (2019), a video on the museum’s website; Well (Whitney version), 2019, consisting of ten glasses of water on small, unreachable shelves in the lobby, galleries, and staff kitchen; and, Choir (2019), a sound and sculptural installation in the lobby and ground-floor gallery. Occluded by darkness with a handwritten sign on its door exclaiming: “DO NOT CLEAN SWEEP MOP THIS GALLERY,” the tucked-away gallery looked like a no-go zone. Upon entry, light seeping in from the lobby slowly faded while faint rumbles of gurgling, sloshing, and dripping grew increasingly louder. The soundtrack’s origin soon became apparent: at the center of what resembled at once a dusty basement, utility room, and echo-free chamber was a sound-generating system topped with an inverted drinking fountain—the quintessential symbol of Jim Crow segregation—suspended over an industrial plastic tank amid a network of cooper pipes and contact microphones. Over forty-minute increments, water furiously poured down from the fountain into a hole atop the dented white thousand-gallon tank. As the vessel filled, a theatrical spotlight illuminated the churning waves inside, evoking the tumultuous waves of the Middle Passage. Fleeting fantasies of an ungovernable deluge surfaced as the water neared the top of the tank, but containment reigned. The flow stopped abruptly before water slowly drained out, presumably through the pipes, into the black walls before returning to the fountain to start anew.

It was difficult to tease apart the dissonant composition produced by these operations. Noise was generated in random patterns by water hitting the vessels containing it. Sloshes mixed with recorded echoey snippets of shouting, laughing, and singing. The artist sourced the clips from blues field recordings and gospel music from African-themed 1930s Hollywood films, then altered the tracks until the lyrics became unrecognizable as language. Haunting, barely legible messages appeared in vinyl letters on the dark walls: first, “NGGR WATER,” then “HL OW WTRR,” then, “NDVSBL WTR.” The last one, a truncated stand-in for “indivisible water,” read as a tongue-in-cheek reference to American singularity amid racist slurs and the symbols of segregation, like the water fountain, ironically underscoring the insistent collectivity of the sound. Conjuring the transformational ecstasy that can result from a choir’s call-and-response with a church congregation, the slow, deep, discomfiting tones reverberated spectral pain. Afropessimist thinkers Fred Moten and Stefano Harney propose that Black social life is fugitive. It persists in spite of deadly racist oppression through shared sensory experiences: “a feel for feeling others feeling you.”11 Their theory of haptics as fugitivity offered one way to understand the experience of Choir. As a non-Black person of Middle Eastern heritage, I thought of Taarab music and its tradition of interactive, ecstatic performance as a parallel reference point. But I remained aware that my experience was not analogous. Violent regimes apply their effects unevenly.

Photo Sai Mokhtari

At the Whitney, a panel discussion addressed how “environmental justice communities”— often comprised of low-income people of color—experience “toxic stress” when they cannot access essentials like clean air and water. The panelists, focused on water crises in two majority Black cities: Newark, New Jersey (Pope.L’s birthplace), and Flint, Michigan (where the artist has worked to provide aid). In 2014, Flint’s emergency management made the cost-saving move to draw water from the Flint River without treating the corrosive water first.12 This was the most immediate cause for the high amount of lead, coliform bacteria, and other pathogens in Flint’s water. Newark similarly had elevated lead levels and recently discovered that one quarter of the filters intended to remove it were improperly installed by residents who had not been trained in how to do so. Lead—used in US service pipelines until 1986 and in private fixtures as recently 2014—is deeply interwoven into our infrastructure, but, as is often the case with things we can’t see, its risk is hard to comprehend. Enter art.

In 2017, in Flint Water Project, Pope.L purchased 150 gallons of tap water from Flint resident Tiantha Williams. Through a bottling factory/shop at What Pipeline gallery in Detroit, he sold the repurposed water as limited edition readymades with proceeds going to nonprofits combatting water shutoffs in Detroit and supporting relief efforts in Flint. His act foreshadowed the controversial permit Nestlé purchased the following year for just two hundred dollars to bottle water from Detroit’s source, for a yearly corporate profit of approximately two million dollars. Pope.L portrayed his intervention as aid from Detroit to Flint, one distressed city to another. It was achievable only because he is a renowned artist, a status he leveraged through the economic tools of philanthropy and art marketing. A Kickstarter campaign, for example, promised “dinner on Pope.L’s lap” to donors of $9,999 or more. Flint Water Meets the Mighty Hudson (2019), a video on the Whitney’s website, shows Pope.L pouring a stream of Flint water—made through editing to seem absurdly long—from a single editioned bottle into the Hudson River. This act combines “Choir” and Flint Water Project, connecting New York to Michigan through an ambiguous web of elements belonging to the infrastructures of water and culture: rivers, pipes, drinking glasses, tanks, vapor in the air, fundraising swag, editioned artworks, mutual aid, donations, fundraising dinners, art sales, etc. Pope.L’s project pursues an Afropessimist strategy of fugitivity. Neither radically alternative nor simply mimetic, the rejiggered system demonstrates how infrastructures that enforce scarcity can be evaded, in this case through mutual aid and creative philanthropy.

COVID-19 has led to temporary suspension of certain practices that negatively impact overall human and environmental wellbeing, primarily for the benefit of the few. There have been eviction moratoriums, deferment of debt payments, the thinning of jail populations, diminished pollution, and the flourishing of mutual aid—glimpses of what could be possible if society drastically changed. But just when many states began to reopen, the possibility of a “new normal” faltered, as police murders of Black people continued. Amid the ensuing uprisings, conversations on police abolition have circulated at unprecedented levels, given the failure of systemic reform. White-led arts spaces broadcast allegiance to racial equity, many without concrete plans for transformation. The question remains whether these institutions can be transformed when they are inextricably linked to colonial and carceral infrastructures. While Pope.L’s ways of coping with infrastructural failings via fugitivity offer one model for life under existing systems, artists in Detroit help us dream what is possible if (and when) such systems are dismantled.

1 For more nuanced grassroots analysis on the history of water shutoffs in Detroit and how they continued despite the Governor’s moratorium, see the Winter 2020 issue of Riverwise.

2 There are long-standing tensions between the region’s Black and Arab American communities, which have been amplified due to Project Green Light, a pay-for-play policing project that began in 2016. Participating local business owners, in exchange for paying a fee and mounting green lights and cameras that feed recordings into a police database on their buildings, get preferential treatment when calling in. The cameras are being integrated with facial recognition software. Arab Americans often own the late-night businesses, such as party stores or gas stations, that use this technology in predominantly Black neighborhoods. For more information on Project Green Light see the August 2019 special issue of Riverwise.

4 For more on Levy and her process, see Sarah Rose Sharp, “An Activist Documentarian Charts Detroit’s Water Affordability Crisis,” Hyperallergic, Dec. 5, 2019.

5 W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk, Chicago, A.C. McClurg & Co., 1903, p. 2.

6 “Structured water” (aka coherent water, aka hexagonal water) is also a term used by a burgeoning industry to market water with a specific molecular structure believed to be more nurturing to life due to its similarities with water unpolluted by human processes. Proponents of its health benefits have been accused of pseudoscience. The connection of Bryce Detroit’s title to alternative health industries alludes to how Black communities often seek out non-institutionalized care, in part due to the pervasive anti-Black bias of the biomedical field. See an analysis of fifteen studies on implicit racial bias’s production of health disparities in William J. Hall, et al., “Implicit Racial/Ethnic Bias Among Health Care Professionals and Its Influence on Health Care Outcomes: A Systematic Review,” Am J Public Health, Dec 2015, 105 (12): e60–e76.

7 While “Rocked a Room” centers a separatist vision, Bryce Detroit and See are part of an ecosystem of aligned diasporic and Indigenous musicians and artists in Detroit. For example, Aadizookaan, meaning “the sacred spirit of the story” in the language of the Anishinaabe, is a collective of musicians, filmmakers, and designers who draw upon ancestral Indigenous-based knowledge systems for multi-media storytelling experiences. Poetic Societies is a Detroit-based quasi-institution that supports residents as they develop creative work through events including poetry workshops, sonic and somatic meditations, healing ceremonies, DJ sets, multilingual R&B albums, and more. These are often transnational exchanges, occurring between diverse communities in cities around the world using the internet. They aim to help participants regain ancestral knowledge lost due to migration, forced displacement, or colonization by connecting through story, food, music, dance, language, and ritual.

9 See Dorothy Hernandez, “Bryce Detroit’s ‘Structured Water’ symbolizes the renaissance of Black music culture in North End,” Model D, Oct. 22, 2019.

10 For more on why narratives of empowerment popularized in the Black Pride Movement were insufficient for Pope.L, see Aria Dean, “The Trickster Art of Pope.L Draws Power from Negation,” Art in America, Nov. 20, 2019.

12 “The Fight for Clean Water” panel took place on March 8, 2020, in partnership with the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). The panelists were Mona Hanna-Attisha, a Flint pediatrician and health advocate; Dimple Chaudhary, lead counsel in a lawsuit to remove Flint’s lead pipes; Kristi Pullen Fedinick, a NRDC scientist; and Yvette Jordan, a Newark public school teacher.

[ad_2]

Source link