[ad_1]

This story about the ‘Katrina to COVID Class’ was produced as part of the series Critical Condition: The Students the Pandemic Hit Hardest, reported by HuffPost and The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.

Satoriya Lambert was still a toddler when Hurricane Katrina struck her hometown. After the levees burst open, her family carried Satoriya to a waiting car on higher ground and they fled the flooded city.

Satoriya is now 18. Last month, because of coronavirus restrictions, she was allowed to bring exactly three family members to her 15-minute, individualized graduation ceremony from Walter L. Cohen College Prep.

All across the nation, students with senior years truncated by the pandemic are feeling a sense of loss as they try to understand what exactly it means to be part of the Class of 2020. But in New Orleans, some have dubbed this year’s graduates the “Katrina to COVID Class,” because their academic careers are book-ended by Hurricane Katrina and the pandemic.

These students trace their earliest memories to 2005. Satoriya, who had just turned 3, remembers looking out the car window to see downed trees and “so much water everywhere.”

The family house that Satoriya lives in now had water to the ceiling. Memories of the disaster are particularly vivid in graduates, like Satoriya, from the city’s Black households, whose homes were far more likely to be in the low-lying, heavily flooded areas of New Orleans due to historic patterns of discrimination and segregation.

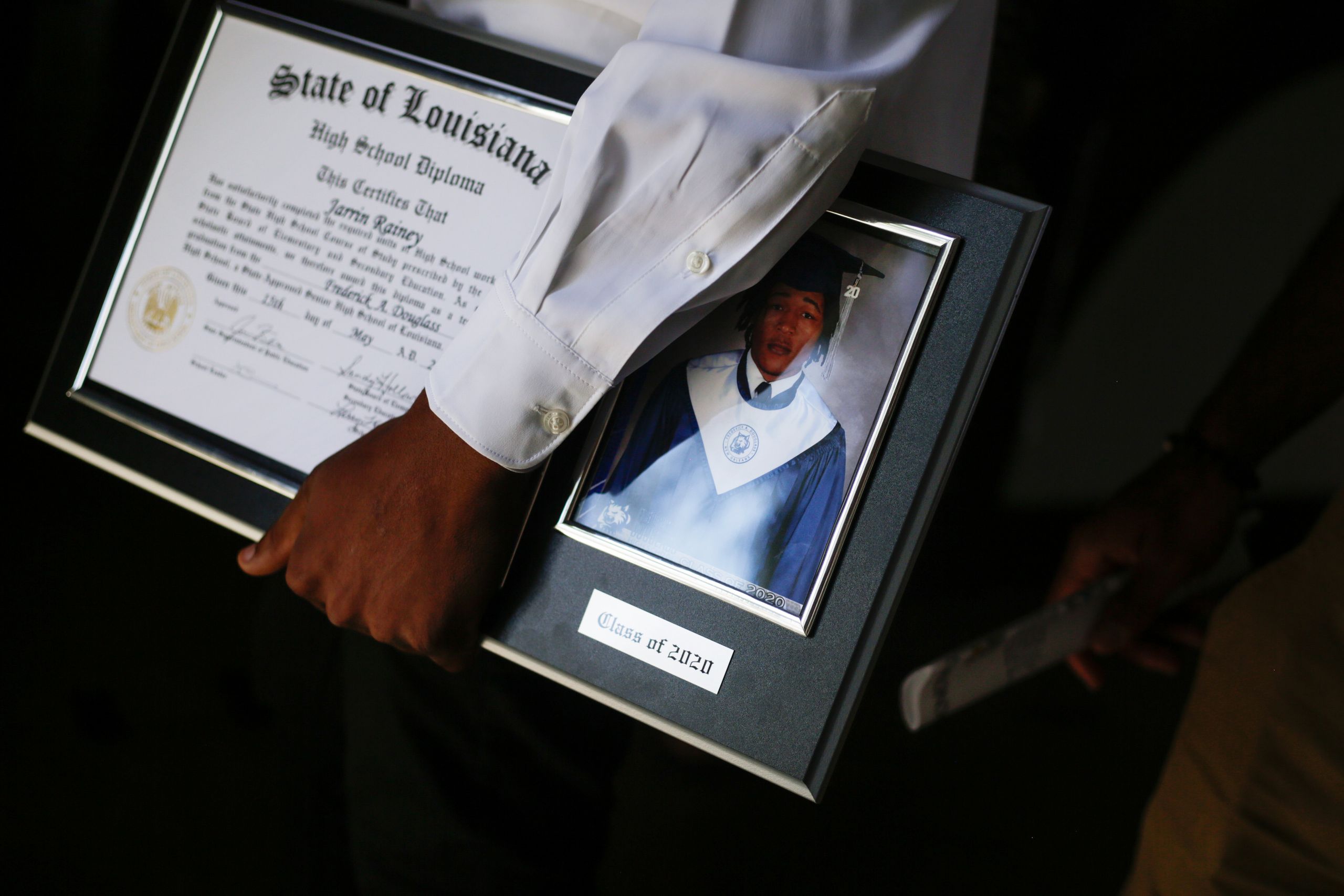

Jarrin Rainey, 20, a 2020 graduate of Frederick A. Douglass High School, remembers his uncles pushing the family to safety in a boat. All he could see for miles was “dirty, nasty water” and ruined, flooded houses, he said.

Mental-health experts say that because of Katrina, those in the Class of 2020 in New Orleans are likely to be more affected by coronavirus upheaval. “We know this is true, though they’re not going to be able to make that connection — ‘Oh, I’m feeling this way about COVID because, you know, early in my life these other things happened,’” said Denese Shervington, a clinical professor of psychiatry at the Tulane University School of Medicine who focuses on community wellness as CEO of the Institute for Women and Ethnic Studies, the nonprofit she founded 27 years ago.

In interviews for this story, some of this year’s graduates described feeling a constant sense of internal struggle. This, too, could be a legacy of Katrina, which affected the way their young brains formed and how their bodies react to stress, Shervington said. “They are going to have memories in their bodies reacting to things they felt or heard or maybe observed, if their parents were in a state of despair.”

Class of 2020 graduate Trevianne Turner, 18, feels a certain tug inside when she looks at the Katrina blight left near her school, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. High School in the city’s Lower 9th Ward. “Sometimes I walk or ride by rundown houses or empty lots filled with weeds and I think, ‘There’s a history back there. What would it have been like without Katrina?’”

That question is personal. Beyond the storm’s visible scars on New Orleans, Trevianne associates it with a series of losses that took a more invisible, internal toll on her life. “My Katrina is different,” she said.

Just hours before Hurricane Katrina began to push storm-surge water into the area, Trevianne Turner’s grandfather, Harry Turner, saw satellite images of the monstrous hurricane spinning over the Gulf of Mexico and decided to take his grandchildren out of harm’s way.

Trevianne and her four older siblings had planned to wait out the 2005 storm in their parents’ home in St. Bernard Parish, just past the southeast edge of New Orleans. Though she was only 3 years old, she remembers her grandfather arriving when it was still dark and hurrying the children into his pickup truck. They drove west to Houston.

Eighty percent of New Orleans flooded; all of St. Bernard Parish flooded. Nearly everyone that the Turner family knew was displaced to other cities.

Because of this widespread displacement, few members of the city’s Class of 2020 started kindergarten in New Orleans itself. Many Katrina-evacuee families stayed on the move for several years, seeking better work and housing. High numbers of evacuee children fell behind in school and suffered unaddressed mental-health concerns, according to a study from Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health.

That instability has likely had lasting consequences. “As much as it’s important for children to attach to a loving family, it’s also really important for them to attach to a loving school as early as possible,” said Shervington. “Because when kids feel safe and connected in school, that becomes a secondary line of defense for them if things should happen at home.”

Trevianne and her family returned to St. Bernard Parish in 2007 to live in a FEMA trailer park. Though she loved school — “It’s always been a major part of who I am,” she said — she didn’t stay in one place for long. When she was attending first grade at Willie Smith Elementary in Violet, her mom died. She was at another school by second grade, at a third school by third grade.

Then, in eighth grade, her grandpa died in his home in St. Bernard.

Broken-hearted, she moved in with her dad in New Orleans and filled out OneApp, the city’s universal application for its public high schools. Her heart fell when she saw her OneApp placement: King High School in the Lower 9th Ward.

She didn’t have a problem with the location; her family had roots in the Lower 9th Ward. But she knew nothing about King, so it had been her last-choice school: No. 8 on her list.

Related: The lost children of Katrina

In the fall of 2016, she started classes in King’s brand-new building, set amid blocks of thick, tall weeds, signs of the neighborhood’s badly stalled recovery from Katrina. She found that most other freshmen had gone through King’s nearby K-8 school. She worried that, socially, she would be an outsider.

But King’s “family dynamic” embraced her in a way she’d never felt before. “By the second week, I felt at home.”

For the first time in her life, she had Black teachers. Though she had excelled under white teachers in predominantly white St. Bernard, she felt that King’s faculty had a better understanding of her struggles. “I found the school more nurturing,” she said. “And it didn’t stop with the teachers. It was the faculty, the staff, everybody.”

She entered her senior year with grades so strong that she hoped to be the top scholar in her entire class. She landed a scholarship to Louisiana State University, where she’ll study pediatric nursing. During Carnival, in February, she paraded happily through the streets in her red-and-white cheerleading uniform.

But a few weeks later, the coronavirus hit the city with a vengeance and the governor closed schools. Friends’ parents got sick; one died. Her family circled around their grandmother, running her errands and isolating themselves from the rest of the world to keep her safe.

In mid-May, school officials hosted a Zoom version of a King tradition — the class roll call. Trevianne participated from her cell phone while standing in her sister’s front yard, with a few of her siblings.

Lindsey Moore, the school principal, broadcasting from the school office, read each name from the school’s official 2020 graduation list, then rolled right into the class’ Top 10 students, starting with 10 and counting down. When he got to two, he paused. Then, in a big, grand voice, he said: “Graduating second in the Class of 2020, Salutatorian Trevianne T. Turner!”

Standing in her sister’s yard, Trevianne looked shocked, then cried. At the very least, she thought she’d be co-valedictorian, she said, as her siblings comforted her. From the phone in her hand, a voice told the class about the upcoming car parade. “I’m not going,” Trevianne said, sniffling a little.

She was still feeling wounded the next morning, as she stood by her sister Taravia’s black Honda Civic. Her siblings were determined that Trevianne participate in King’s Class of 2020 car parade. Balloons waved out of the windows; Taravia used a chalk marker to write slogans on the glass. “Congrats,” she wrote on a side window before reaching across the car’s rear window and scrawling: “We want all da smoke! Salutatorian!”

Along the parade route, crowds were ready. Lower 9th Ward neighbors stood at the curb, waving and cheering. All the way down the street, King teachers, from pre-K to 12th grade, were spaced 6 feet apart, banging on noisemakers.

Taravia cranked the volume on her car radio. Trevianne felt a rush of triumph.

“I’m number two,” she yelled at the top of her lungs, raising her fist into the air. From the sidewalk, the crowd cheered. “I’m number two,” she yelled again. “Number two in the whole class!”

Like Trevianne Turner, Satoriya Lambert got her last choice on OneApp: Walter L. Cohen College Prep. She debated trying to transfer mid-year, but she was hungry for stability after attending three different schools in four years.

For four years, she had blended in. No more. “I left behind the ‘trying-to-fit-in’ in middle school,” she said. “I became my authentic self.”

Along with her determination to re-invent herself, she set lofty academic goals: She wanted to become president of Cohen’s student government and be named class valedictorian with a 4.0 GPA.

She forged strong relationships with her teachers and staff. But Satoriya never felt she got what she needed at the school. The work at Cohen wasn’t challenging enough; she had to settle for xeroxed work packets instead of textbooks. So she worked out the frustrations of the day on the school’s Green Hornets dance team, where she rose to captain.

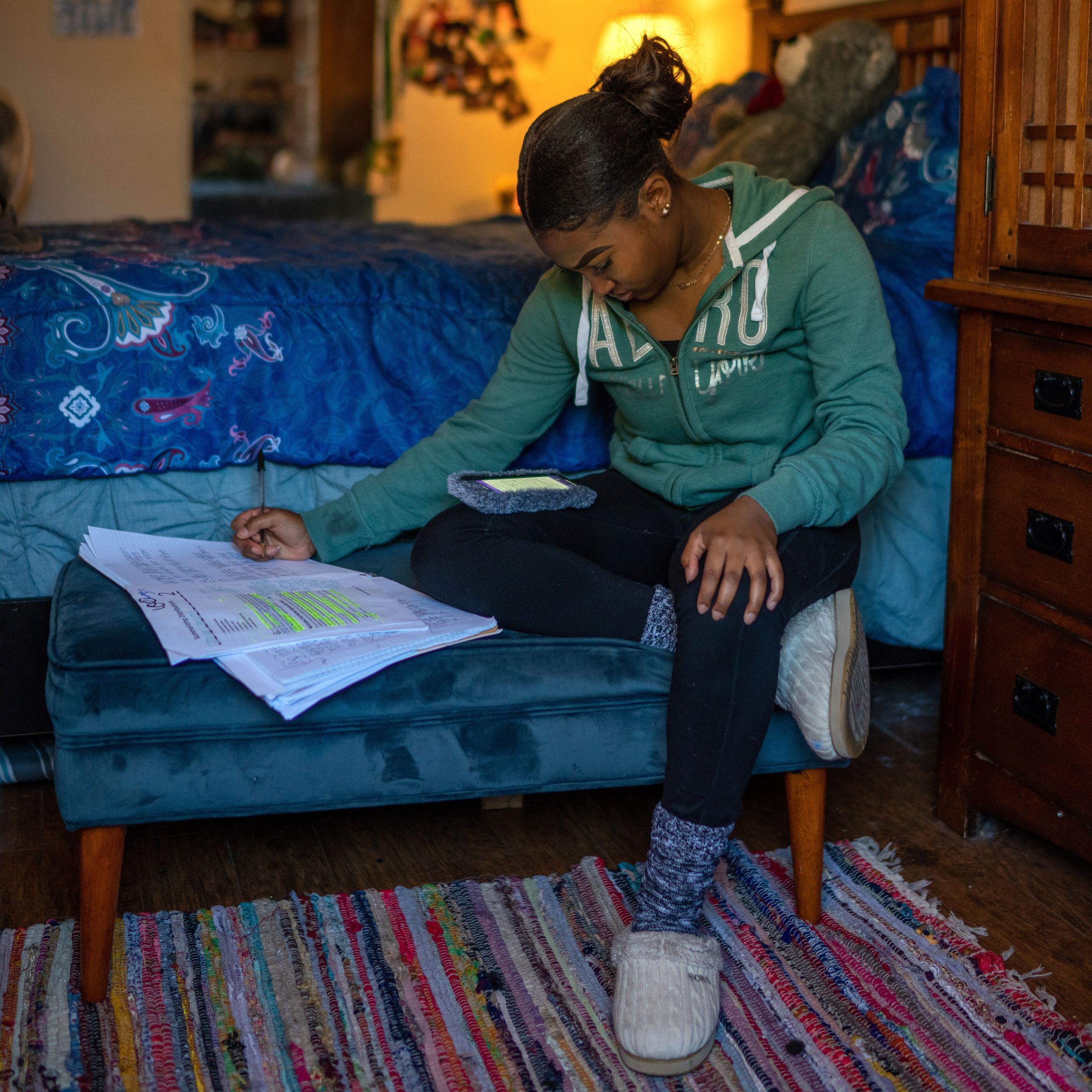

She became known throughout Cohen as a popular but soft-spoken young woman, a self-identified bookworm. Even before the coronavirus brought stay-at-home orders, she usually could be found inside her grandparents’ house in the 6th Ward, where she’s lived since she was 11.

At the start of her junior year, the stability she’d built began to evaporate. Cohen lagged on state performance ratings and attracted about 40 fewer students than it had expected. To balance its budget, the board opted to make emergency staff layoffs, which prompted more staff to leave. Satoriya started her senior year without most of the people she trusted. Darren Lewis, the principal who was hired in 2018 to turn around the failing school, saw how the high turnover affected students like Satoriya. “The people she grew to love chose to leave,” he said.

Satoriya tried to do her part. She had a 4.0 GPA and was ranked first in her class at the end of her junior year. She was elected president of the student council, was voted Miss Senior and became captain of the dance team. She was accepted to Southeastern Louisiana University, where she plans to study business administration.

But she “felt unappreciated,” she said. She wanted more from Cohen than Cohen wanted for her.

During the coronavirus stay-at-home order, Satoriya’s household stayed well. Even their routines changed very little. Her grandma, Ether Bullock, 70, a retired teacher, donned gloves to hand over the trademark fruit-cocktail huckabucks — frozen cups — that she sells to neighbor kids. Satoriya and her grandpa were in charge of the household’s grocery shopping, outfitted in masks and gloves.

As initial fear of the virus receded, she started working at a fast-food restaurant, to make money for college. She also used the quiet time to grow closer to her dad, who was sent to prison on a drug charge a few years ago. They began speaking by phone at least every other day. “I want you to go to school and do better than I’ve done,” he told her. In turn, she told her dad about her frustrations with her school.

A few weeks before graduation, Lewis and an assistant principal made a surprise stop at Satoriya’s job to ceremonially hand her a gold-satin salutatorian sash. Behind them, a car full of customers waiting for chicken honked and yelled, “Congratulations.”

Another student had been named valedictorian, having squeaked past Satoriya with a margin of a few hundredths of a point, said Lewis. But she could still deliver a speech during the school’s rolling graduations, where a single student graduated, followed by another, in filmed, socially distanced ceremonies that will be edited together to create a comprehensive graduation video.

On the last Wednesday in May, Satoriya walked across the stage in front of the three-person audience she was allowed: her grandma, mom, and sister. Then she took the microphone. “Being as I am your student-council president, as a leader, I believe you should always go above and beyond what’s expected of you,” she said. “With that being said, my fellow classmates and I haven’t received a lot of support, but have gotten a lot of hostility, backlash and unprofessionalism from the majority of Cohen’s staff.”

Though staff was present, scattered around the room, and heard her controversial speech, no one said anything to her, Satoriya said. “Nobody even acknowledged it,” she said.

“It was disheartening,” Lewis said later, wondering if Satoriya would have felt the same way if her senior year hadn’t been cut short by the coronavirus. “I’m hoping we will get a chance to discuss it at some point,” he said.

After their separate mini-ceremonies, Satoriya and her friend Jade posed for photos in front of a Cohen Green Hornet photo backdrop. They started to sing, then broke down sobbing.

“I felt her emotion, mine bounced off of hers; hers bounced off of mine,” said Satoriya. “Everything had piled up. We had ruckus and chaos at school, America had COVID and police brutality. We’ve dealt with so much. We needed that moment to release everything that’s going on.”

The front room of Sheila Rainey’s house in the Lower 9th Ward is bathed with a golden glint, from sunlight bouncing off the baseball trophies that crowd the front windowsill, all engraved with the name of her tall, soft-spoken grandson, Jarrin Rainey. He’s a star player at Frederick A. Douglass High School who hopes to keep playing ball next year while taking up welding at a local community college.

Jarrin started school in 2005 as a Katrina evacuee at Bush Elementary in southwest Houston. He recalls missing a lot of school, acting up in class, and running from the school nurse when she tried to give him his prescribed medicine for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Rainey, his maternal grandma, returned to New Orleans before her family, in late 2006, replacing her destroyed family home with a modular structure set on cinderblock pilings. “It’s a trailer, but it’s home,” she said. The rest of the family returned in 2007, a time when the school system was in tumult. Jarrin and his little sister Jamia changed schools so often over the next few years that keeping up with classwork was difficult. Some days, Jarrin, who earned extra money tap-dancing in the French Quarter, arrived at his middle school dead tired. He mostly danced on the weekends, unless supplies in his grandma’s refrigerator got too low. “If it was one of those hungry days, I’d go down there on Monday or Tuesday, just to help us live,” he said.

Then Jarrin met a mentor, Jonny Bartlett, the principal of KIPP Leadership Academy middle school and the varsity baseball coach at the nearby KIPP high school, now Frederick Douglass. Baseball talent had run in the Rainey family for four generations, starting in the 1940s. His grandmother takes pride in Jarrin being a fourth-generation baseball player, part of a family tradition that began with her father and continued with her brothers, her sons, and Jarrin’s dad. Jarrin played tee ball almost as soon as he could walk; he practiced batting by swinging at soda-bottle tops with a broomstick. When he began playing high school baseball for Douglass in eighth grade, he was immediately one of the best players on the team.

But school didn’t capture his enthusiasm. When Jarrin started missing too many schooldays, Bartlett began going to his house every morning, to wake him up and bring him to school. Still, he was held back twice, in fifth grade and again in junior high. “It just made me want to drop out, I ain’t lying,” he said.

Related: Held back, but not helped

He was already 19 when he began his senior year — one of the city’s many “overage” students. A 2018 analysis found that roughly half of New Orleans public-school students were retained at least one year. For Jarrin, turning 19 made him ineligible to play his senior season in baseball. Although the season was scuttled after four games because of coronavirus, Jarrin felt a little lost without baseball to anchor his schooldays.

But his mom and grandma — and Bartlett — urged him to stick it out, and he did.

Before graduation, Bartlett pulled up to Sheila Rainey’s house with clothes for Jarrin to wear: a necktie and the pair of leather shoes that Bartlett had worn at his own wedding. As Bartlett knotted the tie around Jarrin’s neck in the family’s driveway, he got sentimental: “I’m so proud of you, man,” he said. “I love you to death, like a son.”

Typical, Jarrin said. “That’s something he been doing always, for the whole 10 years I’ve known him, making sure I’m straight.”

Bartlett recalled that seven years ago his star player was known for sliding down school bannisters and acting out. Looking back, Jarrin believes he was acting that way because of lagging academics. “I felt like I wasn’t sharp enough in the classroom,” he said.

Because a separate ceremony was held for each student, Frederick Douglass Principal Towana Pierre-Floyd wrote 120 graduation speeches, one for each of graduate. For Jarrin’s, she recalled his freshman year, when he was paired with reading interventionist Ellie Kramer. “You came in like a quiet storm,” she said from the podium, as his grandma, mom, sister, and cousin cheered loudly, along with the teachers and coaches positioned at socially distanced intervals across the school’s auditorium.

“Anything Ms. Kramer put in front of him, he would get it done without fail, without argument — just cleanly, crisply, always got it done,” Pierre-Floyd said. “And when we looked back in May, Jarrin had jumped 300 Lexile points in one year.” She said that was about four times the typical annual growth in reading for his age group.

No one before or since has topped his freshman-year growth, said Pierre-Floyd, as she turned to speak directly to the 6-foot-3 student who’d first shook her hand as a polite eighth grader playing on her high school team. “The thing that’s even cooler is that Jarrin has continued to outpace himself,” Pierre-Floyd said. “Year after year, he’s at these crazy numbers of growth. And he doesn’t show off his skill, doesn’t show off the fact that he’s the greatest grower of all time in the history of Douglass. Instead, he just operates with quiet leadership.”

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link