[ad_1]

As the coronavirus outbreak spread, mosques, like many houses of worship, were forced to shutter their doors even during the holy month of Ramadan in compliance with statewide shutdowns. American Muslims across the country celebrated at home.

With the entire country homebound, many turned to online religious programming, and a silver lining appeared in the quarantine. It opened a space for Muslim women leaders and scholars to hold virtual programming in what is a traditionally male-dominated space. Mosques across the country were suddenly in need of more speakers to fill the void of online discussions, and Muslim women, who were often overlooked despite their qualifications, were now being tapped to host virtual meetups and programs.

The success of these virtual programs ― hosted and led by women for women ― has renewed calls for more inclusive programs to translate over into the physical spaces. With Ramadan over and mosques beginning to reopen with the loosening of lockdown measures, Muslim Americans are using the opportunity to rethink how their houses of worship operate and can survive as the COVID-19 crisis eases.

“It was very sad and a bit lonely praying often by myself or with my mom at home. But at the same time, what I noticed, not just for me but also for women across the country, was that there was a plethora of religious programming that was online and that was particularly alluring to women,” said Hind Makki, a Chicago resident who would regularly go to the mosque during Ramadan to worship and gather with other Muslims.

Outside of Ramadan, Makki considers herself “unmosqued,” not regularly attending a specific mosque because the ones near her lack proper accommodations for women, she said. The inadequate physical spaces, including putting the women’s section in the basement and having few programs that cater to women, turned her away. But after participating in several female-focused online programs, she said, she may not miss the physical institutions after all.

Demanding Inclusive Spaces For Women ― Online And Offline

In 2012, Makki started Side Entrance, a visual storytelling platform where she collected and posted photos of the women’s section of a mosque. Since the majority of mosques are gender-segregated, oftentimes the women’s section was neglected. In her photos, viewers contrasted the women’s spaces with the men’s prayer hall, which often served as the main hall and was better lighted and decorated, and was stocked with more resources.

Women’s spaces were much smaller, despite the fact women frequently attended with their families and children. Sometimes the imam in the main hall could be seen only on a TV, which often broke down. The inadequacies contributed to a sense of it being a spiritually draining space.

“My intention was to start a conversation and provide visual evidence of what women’s experiences are like. The reason to do that was to provide a space for catharsis for women and then to show men who typically don’t ever go into the women’s spaces, or even think about the women’s spaces, what women’s experiences are like,” said Makki.

Makki’s findings have been published in the Reimagining Muslim Spaces study presented by the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU), which is aimed at supporting mosques and community centers to meet the needs of their congregants, especially women, youth and converts.

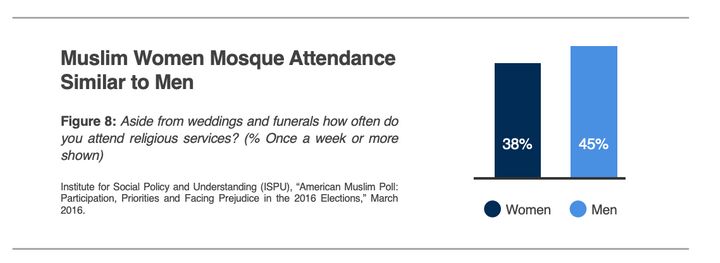

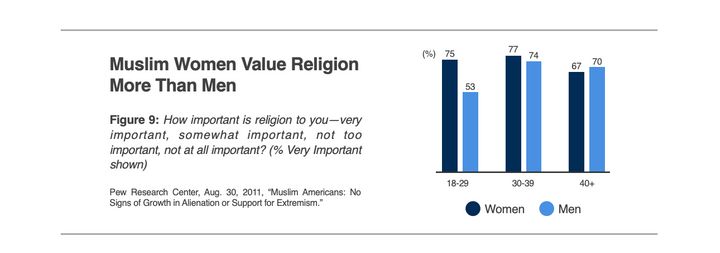

Data from the ISPU study showed that women and men attended American mosques in nearly equal rates and helped form a toolkit for mosques to improve their inclusivity. Specific recommendations included ensuring women were on leadership boards, building attractive and comfortable women’s spaces, and matching resources.

During the coronavirus lockdown, many women like Makki didn’t yearn for the mosque as much as the men did, mostly because they had already chosen to turn away. Many Muslim women had solicited online programs to feel uplifted and connected, even before the pandemic hit.

Rabata is one of those organizations. Tamara Gray was on a speaking tour across the U.S. after being out of the country for 20 years when she noticed that professional Muslim women in America were stifled when it came to Islamic programming and scholarship. Her organization launched in 2012, and soon Rabata became the leading digital educational organization dedicated to women who wanted to learn about Islam and find community among other women.

“We were already building an online community believing and knowing that these communities were saving some women from desperate loneliness,” said Gray, who holds a doctorate in leadership and spent 20 years studying classical Islamic sciences, the Quran and Arabic in Syria. Gray said her goal is to cultivate “a rising tide of Muslim women scholars and leaders and community care activists who are ready and waiting” for when the American mosques are ready to include them in their leadership positions.

During Ramadan, the organization saw an uptick of Muslim women attending programs, sometimes a few hundred a night. Gray knows firsthand that Muslim women are hungry for these spaces, an issue that dates back years since her organization’s founding but was brought into sharper relief as COVID-19 prompted lockdowns. If American mosques want to survive and to ensure that Muslim women come back, the leadership needs to address those gaping holes, Gray said.

“When we sideline women, one of the things we’re doing is sidelining our faith. It is absolutely connected,” Gray said.

Rethinking The Mosque’s Business Model

When mosques closed their doors during their busiest month of the year, their source of stability suddenly was on shaky ground. Mosques often relied on large congregations during Ramadan to raise money for that year’s expenses and to pay their imams, some of whom had been laid off from the mosques. Soon other expenses needed to be cut.

Faisal Khwaja, the co-founder of DeenTek, an organization founded in 2012 to help mosques manage administrative tasks, started to get panicked phone calls from his clients. For years, his organization had helped more than 500 mosques across the country handle their administrative and financial tasks through its most recent cloud management software, MOHID.

But with the lockdown in full effect and their halls empty, mosques could no longer afford to pay for the software, despite their need for it. In normal conditions, about 80% of the donations came from in-person gatherings, according to Khawja compared with the mere 20% that was processed online, posing a challenge for mosques to meet those same numbers solely online. Through the MOHID app and in-house kiosks, mosques were able to raise millions of dollars. During Ramadan last year, American mosques raised nearly $13 million through MOHID.

So Khwaja’s team decided to give away their services and assisted struggling mosques to get up to speed on the technology. The company also launched a free virtual fundraising feature to help clients raise money for annual expenses. He said mosques were at risk of shutting down over their inability to pay the mortgage or keep up with bills because they were unable to engage with the community for donations.

The sacrifices paid off, and the company reported that it was able to help raise over $17 million this past Ramadan for mosques across the U.S. through its virtual platform.

But the problem is beyond Ramadan, Khawja said. Mosques need to develop permanent plans and rethink their business models if they want to survive through this pandemic and possible future ones.

“People are realizing now there are so many other ways to engage the community in ways they never utilized before, although we’ve been trying to tell them for a while,” Khawja said.

“If they are not going to accustom themselves with the technology, if they’re not going to adopt this new norm, they’re going to keep suffering, and we really don’t want that. We are here to help.”

Yearning For Tangible Change

As mosques begin to reopen, some have opened their doors just to men, reasoning that Friday prayers are an obligation for men but not women, until they are able to open fully for everyone. The move has been criticized by Muslim women who see it as unfair and as a sign that Muslim women’s attachment to the mosque is overlooked.

“How are we serving the entire community if we’re reopening only for men, the same people who had always had access to the mosque. We’re not serving the spiritual needs of the rest of the community,” Makki said.

Makki’s suggestion is for the mosques to reopen as first-come, first-served, regardless of gender. Afterall, mosques in America aren’t only for prayers, she pointed out. Many individuals, particularly those who are marginalized or are new to the faith, seek out Islamic centers for myriad reasons, including religious programming, social services and a sense of community.

“The sheer number and enthusiastic response to the women-led religious programming over Ramadan, and even before Ramadan during COVID, should show you that women, like men, also are missing the community and the religious-spiritual support during this time that a mosque should be giving,” Makki said.

A HuffPost Guide To Coronavirus

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link