[ad_1]

When Mazbou Q. saw the video of George Floyd being killed by an American police officer in broad daylight, he didn’t just see the death of one Black man. He saw his own face, and the faces of members of his community, reflected in the footage. It was this realization that led the 31-year-old hip-hop artist and producer to organize a Black Lives Matter demonstration thousands of miles away, in Auckland, New Zealand.

For Mazbou Q., protesting is an expression of solidarity and empathy: “We were reminded of our own mistreatment. We wished to show solidarity with our diaspora cousins in the U.S.”

Beyond New Zealand, protests in solidarity with Black Lives Matter have taken place around the world ― in Berlin, Paris, London, Toronto, São Paulo and each of the 50 U.S. states. I spoke to protesters about why they felt moved by what happened in Minneapolis to take to the streets, even in the midst of a global pandemic.

Laurence Meyer, a 32-year-old jurist who protested in Paris, feels much like Mazbou Q., describing her attendance as an act of mourning. “I can’t stand it anymore. … [Watching the video] of how George Floyd died has reopened a lot of wounds and trauma surrounding our precarious lives as Black people. I am still on the verge of crying when I think about it ― how fragile our existence is in this world and how hated our bodies are worldwide.”

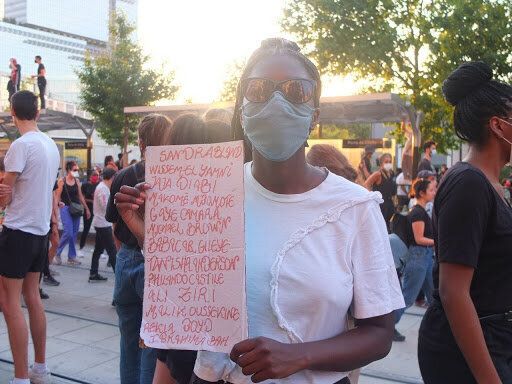

But of course, as anti-Blackness is a global phenomenon, protests go beyond solidarity and also serve as calls for change in governments and police forces around the world.

The statistics on police violence are grim. In Rio de Janeiro state in Brazil, police were responsible for 35% of all killings in April, and Black children are frequently victims of police brutality. In France, the police kill between 25 and 35 people per year, the majority of whom are from ethnic minority and working-class backgrounds. Demonstrations in Paris last week were organized by Assa Traoré, sibling of Adama Traoré, who an independent medical report found was asphyxiated by the police in 2016.

In London, Chanté Joseph, a 23-year-old social media content producer, said she went out to protest because of institutional racism within the British police. “Staying at home wasn’t enough anymore ― I wanted to be involved. In Britain, we have the exact same issues ― just no guns. Black people are eight times more likely to be stopped and searched than their white counterparts.”

Phyllis Quartey, a 32-year-old social worker who supports refugees, said that police brutality was one reason she was motivated to protest in Berlin. “More people need to be aware of what’s really going on in this world we are living in. Germany also has hidden cases in which police officers kill or mistreat Black people.”

She pointed to Oury Jalloh, an asylum-seeker who burned to death in 2005 under suspicious circumstances while in police custody. “His case is still not solved.”

A host of anecdotal evidence shows that policing differs along racial lines in Germany. But police there are not required to keep records of street encounters, where racial profiling often occurs.

Quartey has experienced profiling first hand, including being stopped and questioned by police when walking home at night. “They asked me questions like ‘Where are you going? Where did you now come from?’ using a torchlight directly in my eyes. This situation is frightening, especially when you are alone.”

She also said that institutional racism threads through Germany’s schools. She once filed a police complaint against a teacher who called her son the “n-word” after he was harassed, beaten and verbally abused by his classmates.

In New Zealand, Mazbou Q. said many anti-racist organizers are concerned about the rights of Indigenous people. The Māori population alone makes up over 50% of the nation’s prisoners. “In New Zealand, we are seeing the proposed (and trialed) militarization of the local police force,” he said. “Māori and Pasifika communities here are already victims of disproportionate police violence, which would worsen if the arming of police was normalized.”

Psychoanalyst Victoria Kniest, 27, took to the streets of São Paulo in protest of far-right President Jair Bolsonaro. Brazil has seen a particular assault on Indigenous people, which has only worsened during the coronavirus pandemic. Police brutality surged in that country just as isolation measures came into place.

Kniest said there is widespread police violence in the low-income urban neighborhoods known as favelas. “There are children who die after being hit by stray bullets from operations in the favelas. … When they shoot, the police are not concerned if you are a criminal or not.”

And this too has only worsened during the pandemic. In one case, police opened fire on volunteers handing out food packages to those hit the hardest by the coronavirus.

Kniest said that in recent months in Brazil, similarly to the U.K. and the U.S., Black working-class people have been disproportionately affected by COVID-19. “The majority of those who have to expose themselves to the virus are the low-income population who, in addition to facing precarious work, also face crowded public transport. I went out to protest because I do not believe that we should continue to be hypocritical and blind to who this pandemic will kill: the Black population of this country.”

Globally, it is no coincidence that this movement ― which famed political activist Angela Davis has described as the greatest global challenge to racism we have seen in our lifetimes ― came during a pandemic. For many young people in particular, staying at home means being online, where much consciousness-raising around race has taken place.

“Social media has played a huge role in globalizing us,” said Mazbou Q., “such that we are regularly confronted with the many ways in which our people are oppressed every time we unlock our phones.”

“The interconnectedness of the Black struggle around the world is thus becoming increasingly clear,” he said. “The brazen and audacious manner in which George Floyd was executed in broad daylight in front of bystanders captured clearly that after all this time, our lives still do not matter. And we have had enough.”

We need to radically change the world. There is no other option if we, as Black people, want to live.

Laurence Meyer, a jurist and protester in France

It is not hyperbolic to call this moment historic. Masses of people are supporting the cause of racial justice, both on the streets and online. A petition calling for justice for Floyd garnered over 17 million supporters by June 10, and Black Lives Matter and bailout funds have raised millions of dollars in a fortnight.

Chanté Joseph told me that she believes this time may be different. “This feels like a whole new movement. … Change is definitely coming.”

But as Black lesbian feminist Audre Lorde once wrote, “the revolution is not a one-time event.” For real change to come, pressure needs to continue long after the corporate statements dissipate and the current street protests end.

The disparate dots must be connected across space and time to foster an awareness that Black death is never just an isolated incident, but is a side effect of the structures and ideologies we live with every day. As Davis said, it also means a commitment to rethinking how our society looks and whom we lend power to: “We are asked now to consider how we might imagine justice in the future.”

To keep pushing forward, Laurence Meyer agrees that protesting must be about the system that fails Black people and people must remember all of the lives that have been lost to white supremacy, historically and globally. “We died during COVID-19 to save white lives, we’re dying in the Mediterranean Sea, we’re dying because of the police.”

“We need to radically change the world,” she said. “There is no other option if we, as Black people, want to live.”

CORRECTION: This article previously stated, erroneously, that a Black person is killed by police in Rio de Janeiro every 23 minutes. That statistic includes all killings, not just those by police.

For more content and to be part of the “This New World” community, follow our Facebook page.

HuffPost’s “This New World” series is funded by Partners for a New Economy and the Kendeda Fund. All content is editorially independent, with no influence or input from the foundations. If you have an idea or tip for the editorial series, send an email to thisnewworld@huffpost.com.

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link