[ad_1]

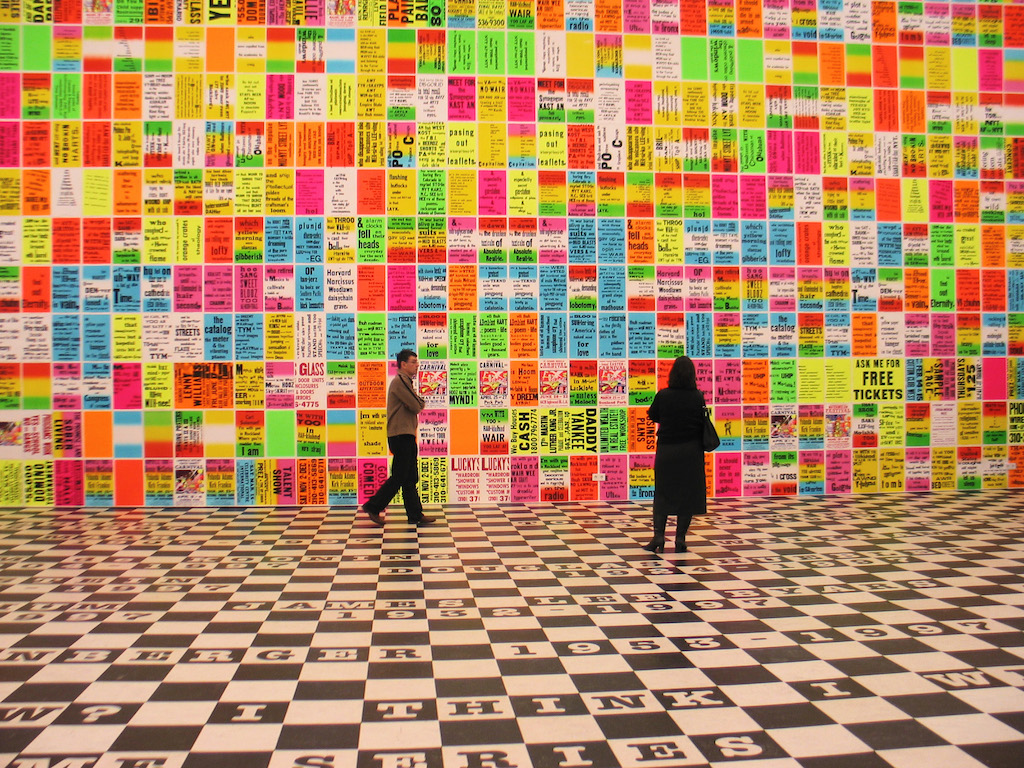

Allen Ruppersberg, The Singing Posters: Allen Ginsburg’s Howl by Allen Ruppersberg (Parts I–III), 2003/05, installation view at Skirball Cultural Center, Los Angeles, 2015.

ROBERT WEDEMEYER

Over the course of his career, Allen Ruppersberg has created a Dadaesque cafe, appropriated versions of famous writers’ letters, and crafted massive installations made from various posters. All of this—and much more—is currently on view in the Ruppersberg retrospective at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, which will travel to the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles next year. To look back on Ruppersberg’s diverse output, we’ve put together excerpts from the archives about the Los Angeles–based artist’s work. Included are musings on his clever pieces about authorship and distinctly American myths—and his work’s weirdness. —Alex Greenberger

“Los Angeles: Abstract and so forth”

By Elizabeth Perlmutter

March 1976

In Allen Ruppersberg’s new work, recently at the Claire Copley Gallery, literary allusion is turned into visual illusion. His visual puns and jests disguise a rage to get and get back at the status and content of literary masterpieces. He seems literally to want to make the stuff of books tangibly real. In The Footnote, three panels of 25 photographs each show shelves from the fiction and poetry section of the Los Angeles Public Library, in full color closeups. A text is handwritten at the bottom of each panel, running continuously from left to right, but discontinuously within each panel. It says: “I believe suicide is the only answer, he said calmly as we finished our usual Friday night dinner together. It was late and immediately after coffee he left for the library, saying that if he didn’t hurry it would be closed for two days. On Monday he was found in the corner by the last row. A few people are now aware of what happened but only closest friends knew his real passion. — Allen Ruppersberg, Black on White (Los Angeles 1974-75).” This text “footnotes” the photographs, which are themselves a cryptogram. The same relation to visual image is borne by the words “View this work with vanity and disgust,” which appear on the left side of a column of five drawings of books called Reading and Drawing, pp. 1-250. In back of each framed drawing are 50 blank pieces of paper; the drawn books themselves range from Wells to Wakowski. Whether the penciled mandate is addressed to the artist or the viewer, or both, is not clear. But this does not reduce the strange coherence of Ruppersberg’s absurdities which, with their urgent words and large handwriting, seems pointing beyond both words and images toward a peculiar hunger to use art to take literature out of books.

“Houston: Surrealism and Voyeurism”

By Charlotte Moser

December 1976

Drawings by Los Angeles artist Al Ruppersberg, showing at Texas Gallery, are flavored with a sense of voyeurism. Ruppersberg enlarged copies of famous authors’ personal letters from the University of California archives, keeps more on a conceptual than a visual level to produce a kind of encroaching intimacy. Keeping his work ultra-personal, Ruppersberg has painstakingly copied the old-fashioned scrawls and paper letterheads, revealing not only the personality but the locale of the writer.

Along with letters, Ruppersberg has also included handwritten film scripts. The scratched-out sections in these documents present the strongest graphic contrasts in all his drawings. Otherwise, the work is characterized by delicate paper outlines and fragile handwriting.

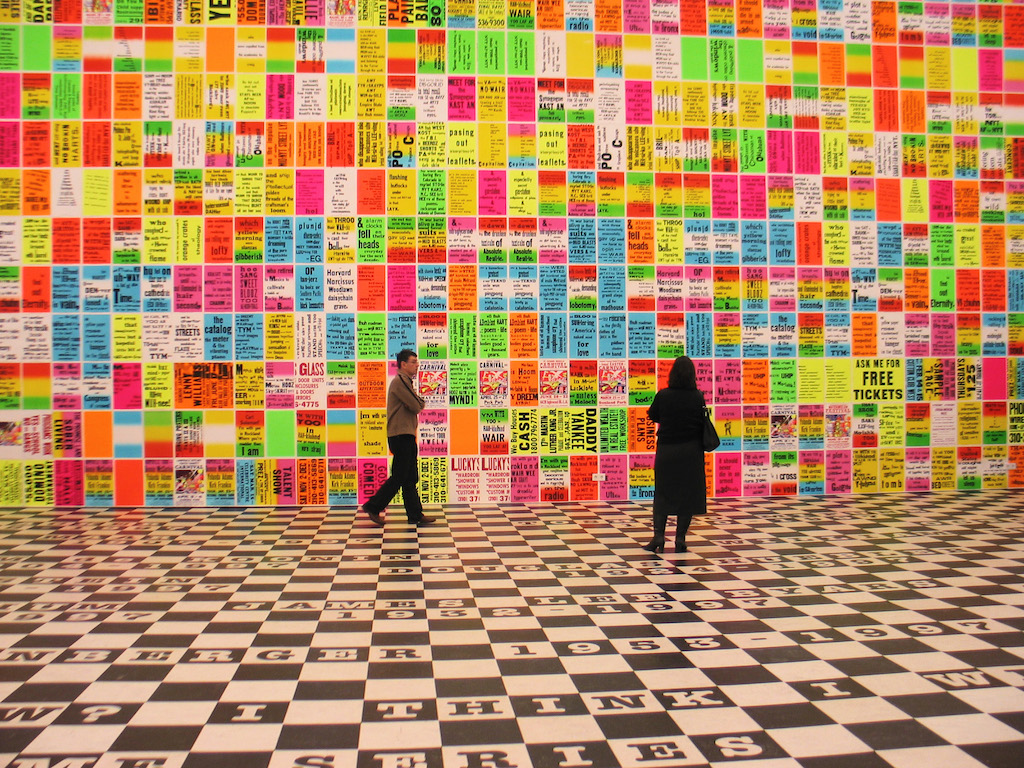

Allen Ruppersberg, Good Dreams, Bad Dreams, What Was Sub-Literature?, 1996, installation view at Aïshti Foundation, Beirut.

GUILLAUME ZICCARELLI/COLLECTION AÏSHTI FOUNDATION, BEIRUT

“Allen Ruppersberg at Christine Burgin”

By Ruth Bass

April 1992

Allen Ruppersberg’s conceptual works are simultaneously concerned with presence and absence—his own, the artworks’, and even the viewer’s. In this show, which concentrated on works from the ’70s, the result was disquieting and memorable.

Great Acts of the Imagination: Volume I World War II (1978) consists of nine hand-drawn reproductions of news photographs from World War II punctuated by actual photographs of a manuscript in a typewriter. By transforming the news photographs into rather bland illustrations, Ruppersberg undercuts their reality and immediacy, while he uses photography to give a sense of importance to typed sentences in a made-up narrative. Thus he presents himself as “author,” while the banal draftsmanship suggests that he is absenting himself as artist. As one focuses on the 14 panels, attention moves away from the physical artifacts and toward the many ambiguous associations they elicit.

“Allen Ruppersberg at Linda Cathcart”

By Suzanne Muchnic

April 1994

You don’t have to be over 40 to appreciate fully Allen Ruppersberg’s installation How to Remember a Better Tomorrow, but it helps. The images, homilies, and sales pitches are straight from an era when schoolchildren were marched off to see films on the ideal way of American life, and when sexist calendars promoted a storybook view of home and health.

Walking through a simulated warehouse of printed material from the 1940s and ’50s, the viewer encountered posters from educational films, sweet pictures of blond kids at play, and cardboard boxes of calendars on themes such as “Going Home,” “True Devotion,” and “Fresh from the Oven.” Ruppersberg, a pioneering conceptual artist who has long dealt with notions of time and cultural myth, even provided an exquisitely detailed model of his idyllic childhood home in Ohio, to personalize the installation and make it excruciatingly real.

Allen Ruppersberg, Remainders: Novel, Sculpture, Film, 1991.

WALKER ART CENTER, T. B. WALKER ACQUISITION FUND, PARTIAL GIFT OF EILEEN AND MICHAEL COHEN, 2014

“Screen Memory: Three London Exhibitions Bring the Past into the Present”

By Jennifer Thatcher

Summer 2017

Freud used the term “Screen memory” to describe a false or exaggerated recollection masking another, more potent one. In choosing the title “Screen Memory” for his group exhibition at Simon Lee gallery, artist-curator Eoin Donnelly acknowledged the term’s original meaning but also used Freud’s theory as an analogy for the ways in which collective memories may occlude or “screen” individual experience. In keeping with an alternative reading of the term—which now also conjures the screens, both large and small, that dominate our lives—most of the works on display belonged to our digital era; however, a selection of earlier collages and appropriation works by Wallace Berman, Sherrie Levine, and Sturtevant offered a sense of lineage.

Allen Ruppersberg was represented by a work that looks older than it is. Poems & Placemats (2008) features color copies of sensationalist newspaper articles, typed texts, and retro-looking found images, laminated and hung on two pegboards as well as stacked inside cardboard boxes—the apparent randomness of their selection at odds with the value and interest implied by their careful preservation. The title encourages viewers to mentally align the laminated elements with the two categories prescribed by the artist, even when a pair of typed poems illogically appear in the Placemats section.

[ad_2]

Source link