[ad_1]

I love “live” albums. The scare quotes are part of it, because what is “live” when you are talking about a recording?

As sound studies scholar Jonathan Sterne writes in his 2003 book The Audible Past: The Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction, recording “does not preserve a preexisting sonic event as it happens so much as it creates and organizes sonic events for the possibility of preservation and repetition.” The person behind the mixing desk at the venue you’re playing might put it differently, but would no doubt agree. What an audience hears of an amplified live show depends as much or more on the way that show is mic’d and mixed as it does on the sound taking place on stage. Record that show for asynchronous listening via other media, and you increase that distance from the stage even further. Or as Sterne puts it, in his effortlessly academic manner, “Recording is, therefore, discontinuous with the ‘live’ events that it is sometimes said to represent (although there are links, of course).” It’s the stress on those links—and the way that stress flexes the chain between recording and performance—that draws me to live albums.

I didn’t always listen to recordings with Sterne’s abstract pronouncements ringing in my ears. I started collecting live albums—bootlegs in particular—because they helped me hear how musicians actually play their instruments. Growing up in the heyday of 1960s and ’70s studio wizardry—Revolver, Pet Sounds, Dark Side of the Moon—records seemed particularly far removed from performance. No one can play guitar backwards. And few live shows will ever feature the sheer number of instruments and voices routinely stacked together by multitrack recording.

But while my teenage bedroom stereo pinged back and forth with psychedelic studio effects, the living room turntable was playing a very different kind of recording. My mother is a jazz singer, and the records she played were far more anchored to live performance. It was easy to imagine that Billie Holiday was actually singing in the house, especially the way my mom listened so intently to her records. Moreover, my mother took me to see her friends perform—and when I heard their records on the stereo, I felt the chain between recording and stage tighten. (Her own performing career was on hiatus at the time, in no small part due to the wild commercial success of the records I was listening to in my room. “Beatles” was muttered like a curse among her jazz peers.)

No wonder I went hunting for live recordings of my rock heroes, especially once I started trying to play in a band myself. And they weren’t hard to find. In the 1980s, bootleg LPs were everywhere, followed in the ’90s by bootleg CDs. All used record stores seemed to have at least a few. And some stores—like Second Coming in Cambridge, Massachusetts—stocked hardly anything else. These stores or their suppliers would be busted by the major labels once in a while, or so rumor had it. But this wasn’t exactly a sub-rosa industry. In 1995, glossy Boston magazine awarded Second Coming “Best Music Store, CDs (Used Popular)” in its annual retail roundup, touting the store’s “tons of imports, CD bootlegs, and unreleased tracks you can’t find at regular record shops.” Residents of the entire region would know exactly where to go for soundboard recordings of Led Zep’s 1973 tour.

Starmavale/Swan Song/Kobal/Shutterstock

This brings up another revelation I gained from bootlegs. Not only could I better hear how rock musicians actually played live music, I could hear how different that music sounded from their commercially released “live” albums. On a soundboard bootleg, even a famously skilled band like Led Zeppelin doesn’t sound as they do in their hyped concert film and accompanying double LP, The Song Remains the Same. The reason should be obvious to anyone using Instagram: editing makes a difference. In Led Zeppelin’s case, the audio equivalent of an Instagram filter might be having legendary producer Eddie Kramer record your live show to multitrack in a truck fitted out by legendary engineer Wally Heider, then mixing it at legendary studios in New York (Electric Lady) and London (Trident). If you’re a powerfully loud but often extremely stoned quartet, the right combination of recording equipment and engineering expertise might even make the difference between sounding like rock gods, and a bar band.

I started to hear more than just editing on commercial live albums. Many—and I mean many—have been tampered with to the point that it’s more accurate to call them “fake live.” Some examples are notorious, like Kiss Alive! (produced by Eddie Kramer again) which reputedly started as an actual live recording, but slowly morphed into something else as track after track after track was replaced in the studio. “It has been generally known for many years that the first Kiss Alive! album was not entirely live,” wrote Kramer, rather tactfully, in response to a direct question from a fan in 1998. “We had to create that album from the live shows with overdubbed guitar because of the fact that Kiss puts on a great show with much leaping about. Obviously, guitars will not stay in tune and accuracy goes right out the window. So, you fix what’s not right.”

Leaping about isn’t the only thing that can send accuracy out the window on a live recording. Duke Ellington’s extremely popular live album from the 1950s, Ellington at Newport—an album that rejuvenated his career in the post–Big Band era—was recorded July 7, 1956 at the Newport Jazz Festival. Except it wasn’t. The ensemble’s performance of “Festival Suite,” an Ellington/Strayhorn composition written for debut that day, hadn’t been up to the maestro’s standards. As if that wasn’t bad enough, when tenor saxophonist Paul Gonsalves stepped up to the mic to take his career-defining, lightning-in-a-bottle, twenty-seven–chorus solo in the middle of “Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue,” he had stepped up to the wrong mic. Producer George Avakian immediately booked time at Columbia Records’ studio in New York, where the band re-recorded the entire set two days later complete with recreated Ellington stage banter and fake crowd sounds.

Sefton Samuels/Shutterstock

And that’s just the beginning of the complex story around this famous “live” album. As a rediscovered Voice of America radio recording of the actual live show later made clear, Gonsalves’s twenty-seven–chorus solo on the “fake live” Columbia record is, in fact, the real live solo everyone heard at Newport. It would seem that unlike the scored “Festival Suite,” this improvised performance proved impossible to recreate in the studio. So Avakian and Ellington doctored the live recording of this track by adding extra audience sounds to mask the mic trouble, burying the sax solo in a mass of ambient noise that arguably made it more exciting to hear on record. (In the late ’90s, radio DJ and producer Phil Schaap reconstructed Gonsalves’s performance without these audience sounds, using the Voice of America tape. That’s likely the version you’ll pull up first on a streaming service today, but it’s well worth digging for both to compare.)

Once your ears are tuned to the inconsistencies found on “live” albums like Kiss Alive! or Ellington at Newport, you start to hear them everywhere. Dream Letter, the posthumously released double CD of Tim Buckley’s beautiful performance in London at Queen Elizabeth Hall on October 7, 1968, begins with the compère walking out on stage to introduce him. The first sounds you hear are footsteps approaching from the wings, starting quietly and then getting louder as they reach the vocal mic.

Richard Drew/AP/Shutterstock

Footsteps from the wings . . . What microphone picked those up? No live show aims mics at the floor—or toward the side of the stage. I must have played that Tim Buckley CD a hundred times before it struck me that it starts with Foley, like a radio play or a movie soundtrack. When I finally did realize, I was listening especially intently because I was busy mixing my own “fake live” album, and trying to match the reverb in the Queen Elizabeth Hall to my manufactured version. It wasn’t hard to do because reverb had also been added later to the Tim Buckley recording. How could it not have been? It sounds so “live”—not like a bootleg at all!

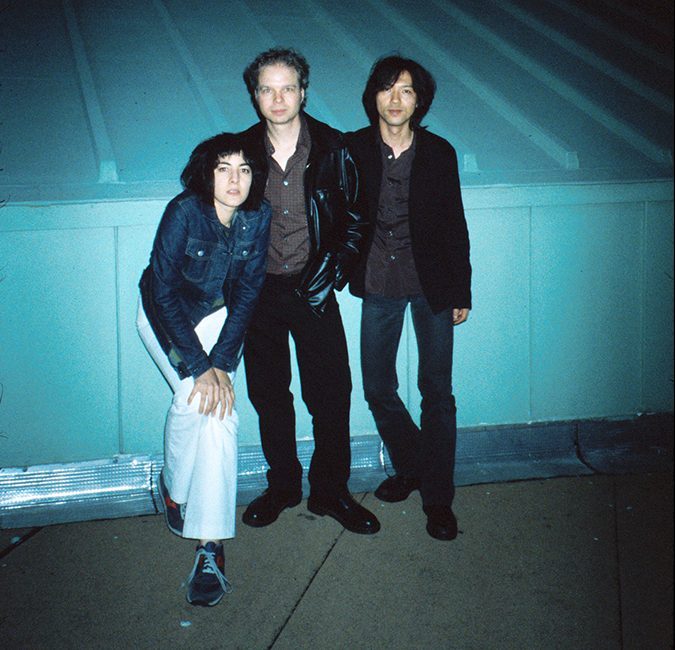

The story of my own “fake live” album is perhaps worth a digression here, if only to illustrate that the circle of this recording tradition remains unbroken. In 2001, my band Damon & Naomi went on a European tour as a trio with the electric guitarist Michio Kurihara. As happens on tour, there was a disaster along the way—in this case involving our promoter in Spain. We canceled a gig in San Sebastian in order to play a television show in Madrid that our record label had scheduled the same day. The promoter—who turned out to be from San Sebastian, and had invited all his hometown friends to the show—was so angered by that decision that he canceled all our subsequent dates in Spain, and decided he was fully justified in keeping the fees for ones we had already played. This wiped out our margin of profit for the entire tour. We flew home broke.

Kurihara had planned a few days’ rest at our place before returning to his home in Tokyo. We all felt frustrated by this absurd ending to what had been otherwise a very rewarding experience, so we decided to play the canceled show that had caused us so much trouble—in our living room. We set up just as we had every night, turned on the tape, and recorded Song to the Siren: Live in San Sebastian (Sub Pop, 2002).

Photo Naomi Yang.

What are “live” records, really? They are, as Jonathan Sterne argues is true of all recordings, “linked” to live events at best. Still, what is the link that makes them feel so “live”? Why does The Song Remains the Same sound more like a Led Zeppelin performance, in all its overheated glory, than an actual soundboard recording does? Why is a studio reconstruction of a flawed Newport Jazz Festival performance the best-selling Ellington record of his entire illustrious career? Why did a reputable indie label like Sub Pop encourage my band to add applause to a recording made in our living room?

The answer is our imagination, and participation. When we listen to a “live” recording, we project ourselves into an event that we couldn’t have experienced firsthand. Indeed, no one could experience Kiss sounding as they do on Alive!, not even the leaping band members themselves. But that active type of listening, linking recorded sound to an event taking place in your mind’s eye—an immersive, fully attentive listening—is an ideal way to hear music.

As a performer, it is also an entirely different way of inviting a listener into your personal space than streaming a show from your couch, or home studio, as so many musicians are now experimenting with under quarantine. Faking a live performance from your living room is not the same as giving one. Watching a stream on Instagram or YouTube, we might witness a true performance, but it is a pale simulacrum of being in a true audience. Alone, lit by the cold light of a screen, our faces set in that passive gaze we all know by watching people watch TV, we are anything but participatory. Closing my laptop after a recent live stream by a musician performing alone in front of their laptop, I only felt our current social isolation all the more.

By contrast, a live album—perhaps especially a “fake live” album—places us in a projected social space. The audience we hear on the recording invites us to join them. Sure, the focus of the recording is whatever once happened, or hypothetically could have happened, on a stage. But the atmosphere we absorb as we listen—the imaginative space we enter in the present—is among the crowd.

[ad_2]

Source link