[ad_1]

Self-taught photographer Robert Giard is best remembered today for his distinctive black-and-white series “Particular Voices: Portraits of Gay and Lesbian Writers.” He was inspired to begin this body of work in the summer of 1985, after seeing two plays that depicted the unfolding AIDS crisis in the United States—Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart and William Hoffman’s As Is. In the introduction to the 1997 Particular Voices book, which paired selected images from the series with short writings by their subjects, Giard wrote, “I had arrived at a decision about my work: that it should be of use to other gay people by recording something of note about our experience, our history, our culture.”

This commitment to producing a visual archive of queer life animated “Uncanny Effects: Robert Giard’s Currents of Connection,” an exhibition at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art in New York. Curators Ariel Goldberg and Noam Parness succeeded both in relaying the extraordinary breadth of the “Particular Voices” project—which continued after the book’s publication and corresponding exhibition at the New York Public Library, comprising photographs of over six hundred writers at the time of Giard’s death in 2002—and in contextualizing Giard’s series in relation to his other work: portraits of artists and activists, nudes, still-lifes, and landscapes.

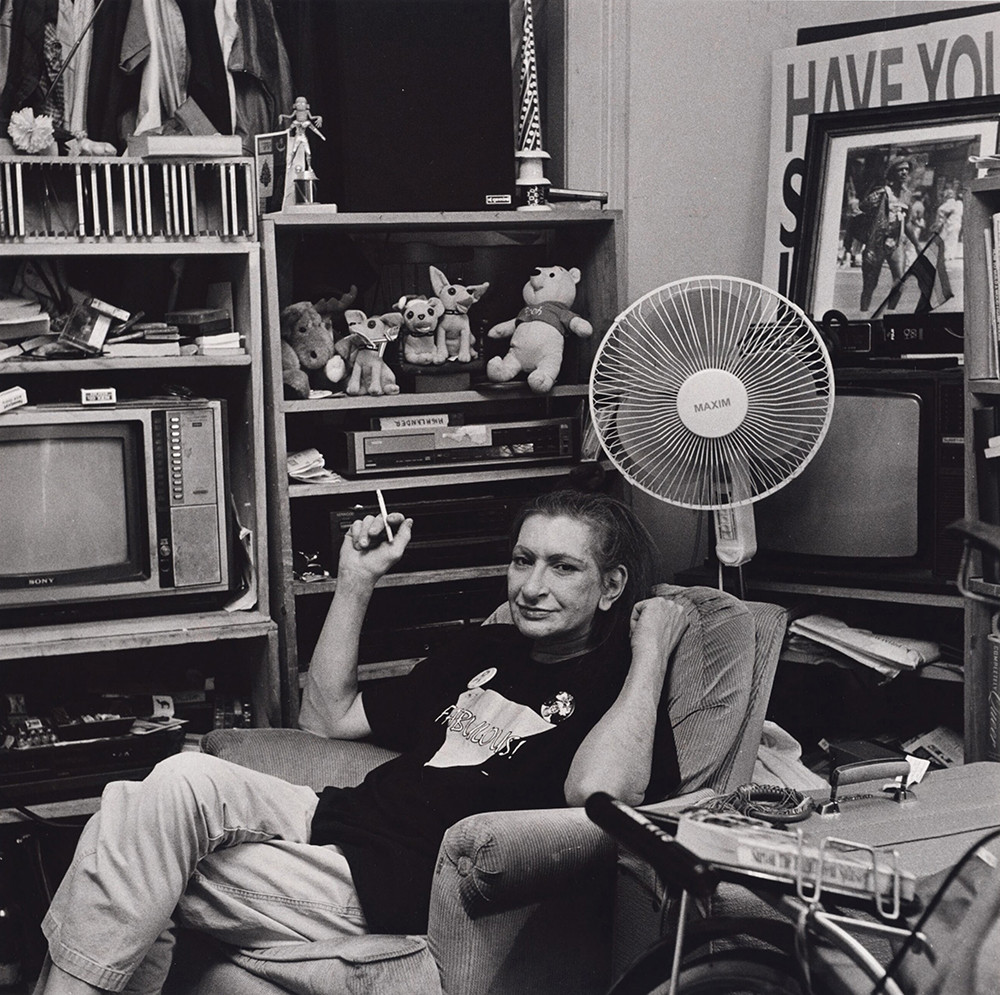

Giard’s portraits tend toward the straightforward: many wouldn’t be out of place illustrating a magazine profile; the most conventional among them could easily double as headshots, and they sometimes did. The most striking portraits assembled in “Uncanny Effects” were those that offer a glimpse of their subjects in their homes or work spaces and, in doing so, reveal something about their personalities or preoccupations: painter Jane Kogan poses nude with one foot planted on the crossbar of a single-mast easel, her bent knee echoing the angle of its base; writer and scholar Melvin Dixon wraps one hand around a column as though embracing a loved one; San Francisco literary icon Kevin Killian, who died last year, sits on a couch surrounded by autographed headshots of cast members from the soap opera “Santa Barbara”; famed gay liberation and trans rights activist Sylvia Rivera smokes a cigarette in an easy chair, a row of stuffed animals peeking out from the crowded shelves behind her.

Courtesy the Estate of Robert Giard.

But the impulse behind Giard’s portraits was never solely documentary, and to accept the photographs at face value is to miss his more ambitious aim: to insist that his subjects—and by extension, their experiences, histories, and cultures—were worthy of documentation. His gaze, at once dignifying and tender, is more romantic than anthropological. In a letter Killian sent Giard after receiving his copy of the Particular Voices book (quoted in the wall text accompanying his portrait), he writes admiringly of Giard’s “loving lens, which has made us all beautiful in some fine-tooth way.” Sarah Schulman’s own handwritten response to the book, pinned to a wall of correspondence and press clippings, wryly notes, “Even Andrea Dworkin has a hopeful quality.” Indeed, though there is a diversity of expressions, poses, and settings among them, what unifies Giard’s portraits—single, double, and group alike—is his almost beatific vision: the silver way light graces skin.

The range of Giard’s subjects is also notable. “Particular Voices” highlights writers of various genres and aesthetic affiliations, from the mainstream to the margins, and while white writers constitute the majority of the subjects, Giard, who was himself white, photographed many writers of color for the series as well. (Despite naming only gays and lesbians in its subtitle, “Particular Voices” also includes some portraits of bisexual and trans writers. Giard’s provisional description of “Queer Views”—his final, unfinished effort to photograph early queer activists, for which he made the portrait of Rivera—explicitly names trans activists as a part of its scope.) Giard was dedicated to looking beyond his immediate social sphere for subjects and traveled extensively to shoot (though he lived at the far end of Long Island and did not drive), using his art practice as a way to build relationships and continually expand his network. In the Particular Voices book, he recounts how degrees of separation turned into new connections—for instance, a close friend introduced him to Assotto Saint, who, in turn, led him to Samuel R. Delany, Sapphire, and the Other Countries collective of black male writers. “This pattern would repeat itself,” he continues, “as one writer would lead me to others and I accumulated numerous scraps of paper bearing names, addresses, phone numbers, and book titles. Thus began the process of haunting the bookstores, reading the work of an author, communicating first by letter, eventually following this up with a phone call, setting a date, and finally traveling to the writer to make a portrait.”

It’s an involved, antiquated method, the memory (or notion) of which the excellent ephemera in this exhibition made easier to conjure. While it’s impossible, in this moment of social distancing, not to be grateful for the wonders of digital technology, “Uncanny Effects” produced in me a nostalgia for a kind of queer sociality that I’ve never really known as an adult, for a time when to reach out to an author—or to read their work, or even to know what they looked like—required more than a quick click. Still, it seems right that so many of Giard’s portraits can be found online, where they remain accessible to the greatest number of viewers. His landscapes—austere images of the Hamptons in the off-season—might be more the mood now, but, ironically, you’d have to see them in person to truly appreciate the story they tell about isolation, absence, and presence.

[ad_2]

Source link