[ad_1]

Years after Valerie Solanas had shot and almost killed him, Andy Warhol recalled his first return to the Union Square studio where the shooting had happened in 1968: “I was confused because I wasn’t painting there and I wasn’t filming there,” he later wrote. “I would just sit in my tiny office and peek out toward the front at Paul [Morrissey] and Fred [Hughes] taking care of business.” Before long, however, it dawned on him that in “taking care of business”—shooting movies under his name, selling his prints, and finding him portrait commissions—his peons were executing a new kind of art for him, the way his assistant Gerard Malanga had executed some of his silkscreens. “I knew that work was going on, even if I didn’t have any idea what the work would come to,” Warhol wrote. That corporate “work” turned out to be some of the most important art he ever made—“Business Art,” he came to call it, “the step that comes after art.” It established that everything this artist would do as head of Andy Warhol Enterprises, Inc.—as portraitist, publisher, publicist, celebrity, or salesman—counted as components in one boundless work, part performance art, part conceptual art, and part portrait of the market world he lived in.

“You’re a killer of art, you’re a killer of beauty, and you’re even a killer of laughter,” said a drunken Willem de Kooning to Warhol at a party at the end of the ’60s. The last of America’s Old Masters was right; he just didn’t realize that he’d zeroed in on the true, important achievement that would dominate Warhol’s later career.

“The new art is really a business,” Warhol told a reporter, late in 1969. “We want to sell shares of our company on the Wall Street stock market.” That never happened and was probably never supposed to. But, coming after his 1950s persona as a fay window dresser and his ’60s costume as a shade-wearing hipster, Warhol’s ’70s uniform as hard-headed capitalist, at the head of any number of corporate enterprises, must have seemed right for the times. “I’m a commercial person,” he said in a documentary shot in the early years of the Union Square studio. “I’ve got a lot of mouths to feed. I’ve gotta bring home the bacon.”

He almost always billed his society portraits as a purely financial venture, easier and more profitable than the other arms of his corporation (which they were) but also more annoying (which they also often were): “If we could just make a living out of movies or the newspaper business or something—it’s so boring, painting the same picture over and over,” he said, after doing just that for the better part of a decade.

He was equally forthright about how little creative investment he had in the later films. From Flesh onwards, he was happy to give his collaborator Paul Morrissey all the creative credit for the movies that came out under the Warhol name. (With the exception of the almost-pornographic Fuck, which Morrissey wouldn’t have wanted on his resume, anyway.) Warhol recognized that his own role was limited to funding and branding: “What’s funny,” he said, “is that people pay three dollars because it says Andy Warhol.” He knew that the late movies became true “Warhols”—that’s how they were almost always described in the press—only as instances of his new Business Art, which meant that his CEO persona gave him yet another chance to play with normal notions of authorship, and to undermine them. All this drove Morrissey just about mad, since he felt he was the only real “author” of the movies he directed and could never understand the more complex, avant-garde games Warhol was playing in accepting a role as a new kind of corporate creator.

“The new art is really a business. We want to sell shares of our company on the stock market.”

Warhol’s role in Interview magazine was also more supervisory and managerial than strictly creative. It, too, eventually bore his name—the publication became Andy Warhol’s Interview in 1972–even as he was surrendering almost all the work on each issue to a team of more or less talented underlings. The fact that it didn’t chalk up a profit didn’t make it a failed artwork, even in Business Art terms. If the magazine didn’t find a buying audience, that just made it like so many of the more adventurous art objects that Warhol had turned out over the years. Its losses could be likened to the costs of the art supplies that had gone into Warhol’s least understood Pop paintings. As a good avant-gardist, Warhol knew better than to judge a work by the reception it got from the public—a lack of public could even be proof of a work’s long-term importance. That applied to his creations as a Business Artist as much as to any objects he made. Unlike any real commercial enterprise—including the making and selling of paintings—Warhol’s Business Art counted as a success even when it didn’t bring in a penny.

In the mid-1970s, Warhol (or a ghostwriter) summed up his position with a famous proposition: “Being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art. Making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art.” But like most Warholian aphorisms, that one doesn’t shed much light on what he was really up to, since the “business” he took on was only rarely “good,” at least in standard Wall Street terms.

The real, very Warholian creativity came in making the statement at all rather than in trying to realize its claims. Coming up with the conceit of Business Art, that is, let Warhol produce objects and offer them for sale while insisting that the offering, more than the objects, counted as the art. It was the performance that mattered, not its cash results. In the early 1980s, when Warhol was often billed as a full-blown sell-out, he reacted with unusual venom when his print dealer said they were going to be having a chat about Warhol-brand bedlinens. “No. We’re not,” Warhol told him. “Sonny, I’ve turned down millions of dollars in deals for sheets and pillowcases and I’m not going to do it for you.”

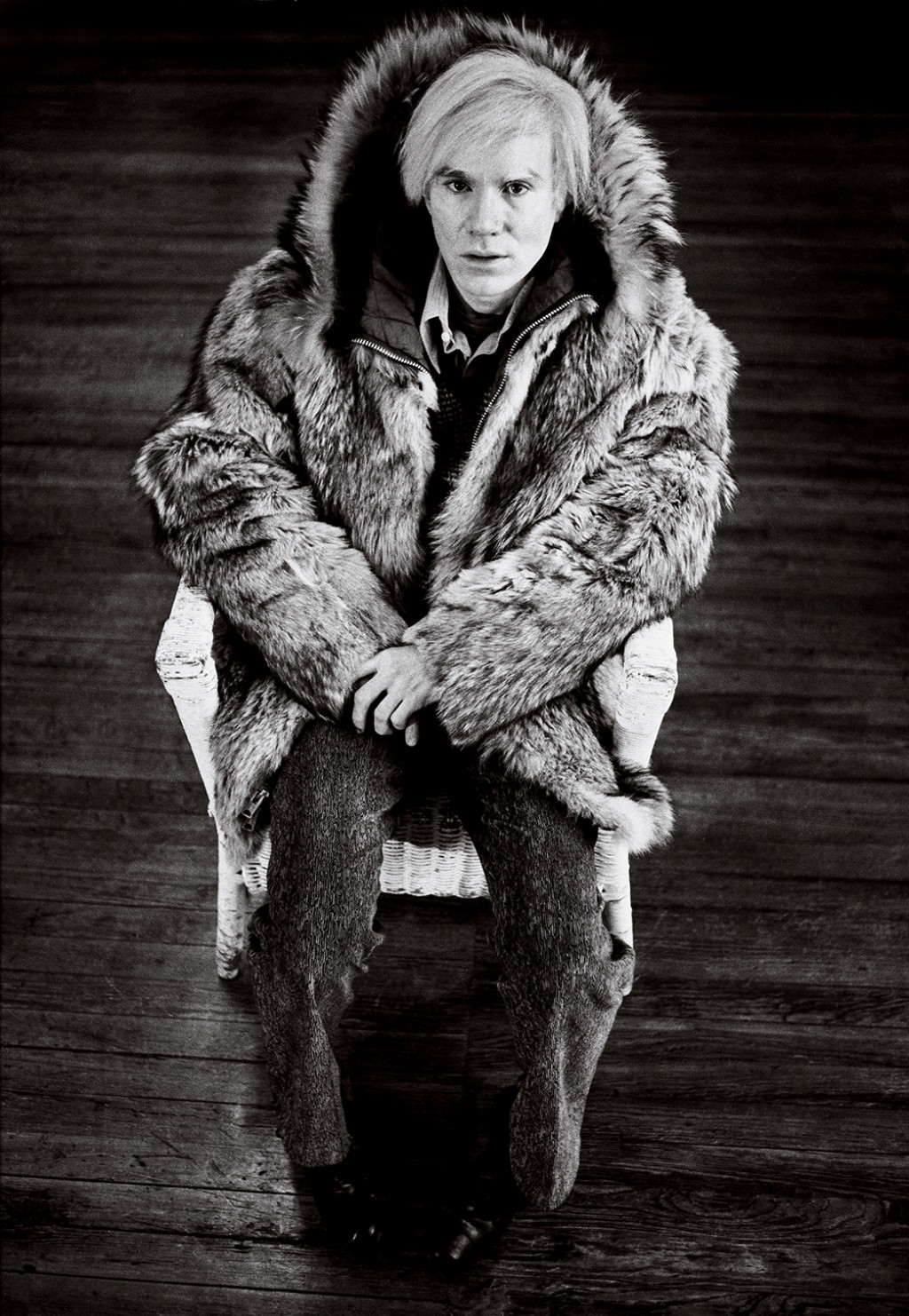

Erik Pendzich/Shutterstock

The aphorism that “Good business is the best art” tells us less about Warhol’s real desire for success in business than it tells us about his eagerness always to move forward into virgin territory in art—in this case, by dressing it up as business. Irving Blum, an art dealer and collector who was the first to show Warhol on the West Coast, remembered that, for a while after Warhol’s near-death experience, he’d been convinced that Warhol’s career had come to an end. “Many people thought that,” he said, “and we were wrong.” Very.

Although Warhol only really took on the full mantle of Business Art at the tail end of the 1960s, the groundwork had been laid from the earliest days of Pop. After all, the very first Pop work of his that got into a show was an image of 200 one-dollar bills that he priced at $200, thereby coming just about as close as you could to reducing art to its exchange value. That was certainly a subtext in almost all the paintings Warhol went on to make. Even—or especially—the jolly, apparently superficial Flowers of late ’64 could be described by one critic, already writing in almost Business Art terms, as “empty metaphysical vessels that are continually being filled with real money, which is an undeniable triumph, sociologically.”

Warhol’s own people could buy into this image of Warhol’s art as essentially mercenary. “Painting was for Andy not art at all but a way of gaining as much capital as possible,” Malanga once recalled, admittedly in a moment of post-Warhol dudgeon. “The least thing ever on Andy’s mind was art, or a very twisted or distorted sense of it. What was merely passed off as art only took a few minutes to execute—for me to silkscreen—while he reaped the financial take.” Malanga wasn’t entirely wrong. With his rejection of the handmade and of conventional, personalized authorship, Warhol had been functioning as the CEO of an artmaking “factory” for several years, very much in the tradition of past art-world CEOs such as Vasari or Rubens. “Was Michelangelo a businessman?” asked a reporter. “Yes, he made a lot of money while he was working,” replied Warhol. What’s most interesting about Warhol’s version of that venerable role is how eagerly he promoted it to his audience.

“The least thing ever on Andy’s mind was art, or a very twisted or distorted sense of it.”

An ad he placed in the Village Voice in 1966 read as follows: “I’ll endorse with my name any of the following; clothing AC-DC, cigarettes small, tapes, sound equipment, ROCK N’ ROLL RECORDS, anything, film, and film equipment, Food, Helium, Whips, MONEY!! love and kisses ANDY WARHOL, EL 5-9941.” Such a public announcement—it used the real Factory phone number—can’t only, or mostly, have been a way to truly bring in cash or goods; it proclaimed that, henceforward, selling-out and branded sponsorship would count as signature Warhol moves. Or maybe as his latest art supplies.

He talked in similarly open terms about aiming to make profits off the most esoteric of his movies—even the utterly unsellable Four Stars, with its 25-hour running time and incomprehensible action. In fact it was in discussing the surprise profits from the equally challenging Chelsea Girls, just as he was moving into his businesslike new studio, that he came out for the very first time with the claim that “the new Art is Business.”

Kirsty Wigglesworth/AP/Shutterst

This had become so obvious, even in the mainstream, that already in February of ’68, Monocle magazine was inviting Warhol to contribute to a goofy survey it was doing that asked the question “Why I sold out.” As the editors wrote to him, “we feel our coverage of artists would be woefully inadequate if you were not represented.” Although to our ears this may sound like an insult, they could hardly have meant it as that; at the time, Warhol’s self-portrayal as a Business Artist was clearly beginning to gel in the public imagination as yet another of Warhol’s zany conceits. Out on art’s cutting edge, it might even have been seen as a necessary and brilliant esthetic move, given the widespread sense that object-making had become a dead end and that some kind of conceptual art or real-world performance would have to be the way forward. Money and business were frequent subjects of this new “social sculpture,” as it was called by the German art star Joseph Beuys. (In one 1983 tally of artists’ press coverage, Warhol came second only to him.) When another artist attacked Warhol as “without talent, a publicist and not an artist,” Beuys leaped to his defense: “Andy Warhol has—and that’s where I relate to him—been able to draw society, work, business into his art.”

Business-as-art was already in play as early as 1965, when the poet John Giorno, Warhol’s ex-boyfriend, had founded his company called Giorno Poetry Systems as a way of “playing with corporate models,” as he put it. Within a few years, the art press was giving front-cover exposure to Iain and Ingrid Baxter, of Vancouver, when they became the N.E. Thing Co., offering (pseudo-) corporate services of all kinds—and calling it art. (Warhol kept announcements of their shows.) In New York, Les Levine, a friend and rival of Warhol’s, had opened and run a restaurant—as art. He also bought 500 shares in a volatile stock and declared that the profits or losses from the investment would count as a work of art.

By 1969, Life magazine, no less, could feel comfortable running an entire story on these money-games that artists were playing. It was almost certainly written by David Bourdon, the Life staffer who was Warhol’s close friend, and featured Levine’s stock-market work and another piece that asked the Whitney Museum to take out a $100,000 loan against its collection and to invest the amount instead—as art. That piece was by Robert Morris, whose sculpture Slab (one a critic had dismissed as a “model stand”) had sat in front of Warhol’s dollar painting in the same group show that had revealed his Pop Art for the first time, back in 1962.

Kobal/Shutterstock

This was the art-world context that Warhol’s notion of Business Art was born into, and reveals it as the latest example of his desperate desire to keep up with his artist peers, and to leave them in his dust. Whereas Life’s roster of Business artists mostly did their corporate work in museums and galleries, with a wink and a nod to their audience of insiders, Warhol dove deep into the real business world, deliberately confusing the categories of “business” and “art” as no one had before.

That made it possible for the critic John Perreault, writing already in the early ’70s, to talk about how “the business of art, as Warhol has hinted at through his works, can be the subject of art” and how “the art system itself can be an art medium. In a business culture, art business can become an efficient comment, not only upon art, but upon business and upon the business culture.” Or as another critic put it, after contemplating Warhol’s new status as corporate commodity: “Merging life and art more closely than any Dadaist or Surrealist could imagine, Andy is the Zeitgeist incarnate.”

And yet Business Art wasn’t a pure abstraction for Warhol, or some kind of facile conceit, as it was for his peers in conceptualism. He was at least as eager a craftsman when working on his new, corporate production as when he was making paintings or films. He realized that, once he decided to take on a Business Art project—and there were plenty he left by the wayside—it ought to be well realized. According to one staffer who first arrived in ’69, “business advisers were always amazed at how good Andy was at really understanding the basic concepts of a deal and getting it across—and Andy was very good.”

Warhol had started out in Business Art with projects that only played at commerce—those endorsement ads in the Voice; his You’re In perfume—and some later ones were hardly more credible. No one was really going to rent his Superstars for $5,000 apiece; would paying customers really flock to a restaurant for people who preferred to eat alone—in front of a TV? But it wasn’t long before the new, Union Square version of Warhol really did reach out in all directions for commercial opportunities. He tried to get German TV to pay him $600 per minute of on-camera time. (The producers declined.) He agreed to sponsor editioned multiples of all kinds, from Warhol-branded bricks to a Marilyn-shaped soap to Warholian Jell-O molds. (He had a lifelong love of aspics and jellies.) In 1976, the catalogue for a high-end department store was selling his services as a private filmmaker for $150,000; a decade later, a different catalogue was offering his custom-made portraits, at $35,000 a pop, in a project promoted by Aramis cologne. (Buyers would also get their portraits reproduced, “for free,” on 900 custom Christmas cards.) Ideas that never quite matured included a chain of shops that sold goods of one color, a Warhol makeup line, and also ties made from his paintings’ cut-offs. It was never easy to tell which of these counted as simple business propositions and which were Business Art conceits. But the whole point was that, with Warhol, the two were exquisitely, agonizingly blended.

Erik Pendzich/Shutterstock

Anyone with more traditional notions of art could dismiss his new corporate persona and practice as purely venal. When a: a novel was released in the winter of ’68, the critic at Newsweek complained that it wasn’t really by Warhol at all: “He has neither edited it nor written it; he has merely marketed it.” But of course that was what made it so distinctly one of Warhol’s new works.

Even Warhol’s dear friend Brigid Berlin had a hard time wrapping her mind around this new model. She may have cultivated an extravagant weirdness in her person, but her lack of art training left her stranded when it came to the far reaches of “social sculpture” where Warhol was setting up shop. “I think Andy is a business genius. I don’t think he’s an artist. He’s in another field all of its own. He should be in some town like Chicago, in a big tall building, with his office and his secretaries,” Berlin said in a video shot in 1971, before Warhol had even gone far yet with his Business Art. “He gets me really upset when the only thing he can talk about is money. . . . If I try to talk about art with Andy, he steers me off. He completely steers me off.” He realized, as Berlin couldn’t, that the most interesting way to talk about art, at that moment, was to talk about money. The truth is, most of the art world couldn’t follow him when he went there.

Only Warhol’s most cutting-edge fans could see that his new practice from inside the world of commerce might also hint at a critique of it. Warhol’s earlier Pop objects had already “exposed the shoddy mechanics of both contemporary art and society,” wrote his lefty friend Gregory Battcock. The artist’s final rejection of art of all kinds—of the “form of art itself”—was the most appropriate next response, said Battcock, to “an art and culture market that has debased every shred of meaning that picture making may have had.” By declaring Business Art to be the “step that comes after art,” Warhol was setting it up as a repudiation of what had come before. That idea of John Perreault’s that “art business can become an efficient comment, not only upon art, but upon business and upon the business culture” implied a “comment” that was also a diss.

The critique implied in Business Art also functioned as a dose of self-protection: Warhol could never be accused of selling out once he’d declared his sell-out to be a work of art with a critique built in. Just when Warhol’s final illness was laying him low, one young critic was grappling with the fact that even work by Warhol that was evidently “bad” and clearly made for purely commercial reasons (there was plenty of it, in his last decades) might actually be functioning as a superlative work of Business Art. What was a fan to do, wondered the critic, with the fact that Warhol’s latest self-portrait—his final one, in fact—“has been rendered on canvas in small, medium, and large, on T-shirts (extra extra large only), and used in an advertisement for retail-brokerage services for individual investors”?

In 1917, Marcel Duchamp had taken a humble urinal and, simply by declaring it art, turned it into the most influential work of the 20th century. Five decades later, Warhol proposed treating the product launch, press release, and spreadsheet as art. That had an equally profound effect on the 50 years of art that have followed.

Adapted from the biography Warhol by Blake Gopnik, published by Ecco on April 21. ©2020 Blake Gopnik. Reprinted with permission from The Wylie Agency, LLC. All rights reserved.

A version of this article appears in the Spring 2020 issue of ARTnews, under the title “‘He gets me really upset when the only thing he can talk about is money.’”

[ad_2]

Source link