[ad_1]

Relevance is more easily claimed than earned. The concept of The Art We Need Now is built on a few rickety premises: “we” are all the same; we “need” art; art that can be enjoyed “now” is preferable to art that takes time to digest. I have no idea if anybody especially needs Kevin Jerome Everson’s films right now (I have to imagine most people in this pandemic would rather have an extra mask or two). But the recent showing of his work at Andrew Kreps coincided perfectly with the revival of a national conversation involving the clumsy euphemisms of labor—“essential” versus “nonessential,” “unskilled” versus “skilled”—that Everson has spent his career pulling apart.

The exhibition centered on a pair of wonderfully sharp short films shot on 16mm and transferred to video, Westinghouse 1 and Westinghouse 3 (both 2019). Taken together, the films brought to mind the great historian E.P. Thompson’s claim that he was trying to “rescue” the working class from “the enormous condescension of posterity.” The claim itself might sound condescending—who says that workers need someone to rescue them, or that an academic is the right person for the job? The nearly two hundred films that Everson (himself a professor at the University of Virginia) has completed since the late 1990s confront similar ethical/aesthetic challenges: how to film workers without fetishizing work; how to study their behavior without risking a chilly remove that smacks of Taylorism.

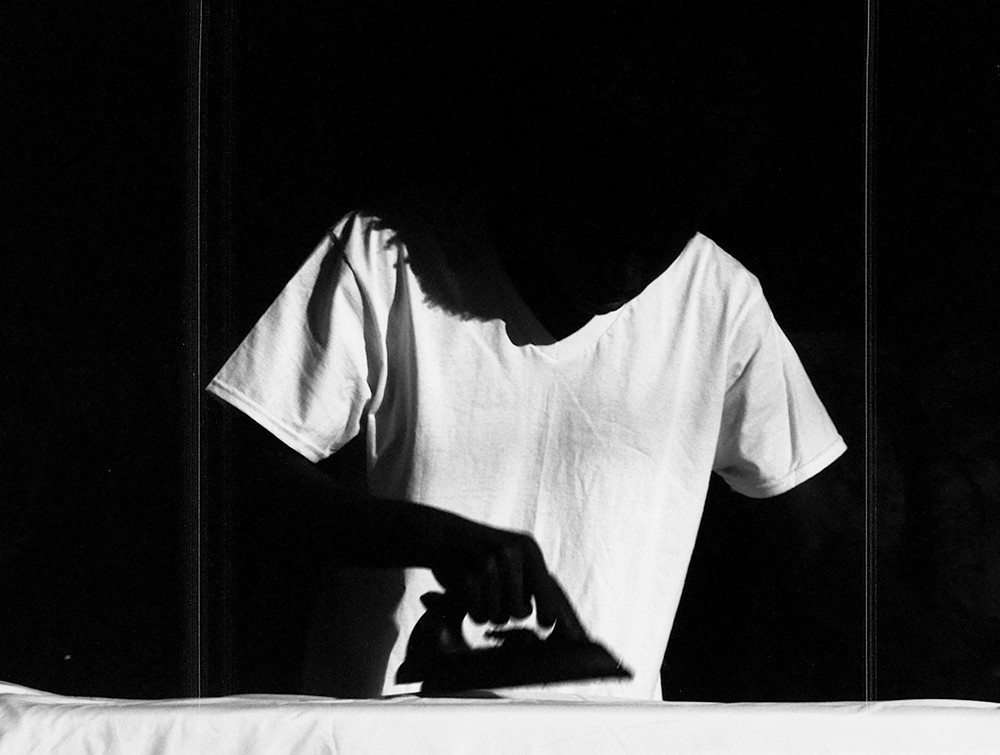

One strategy is to offer two nuances on the same subject. Both “Westinghouses,” which played simultaneously, on loop, on opposite walls, show a young black man, Everson’s cousin Derek Whitfield, ironing a white sheet, but 1 is black-and-white and three minutes long, while 3 is a slightly shorter color film. (Westinghouse 2, in which a young woman performs the same task, wasn’t included). The films’ differing lengths—as well as the six rubber “irons” displayed around the gallery space—prevented the exhibition from feeling like an exercise in symmetry for its own sake. The sense, instead, was of a vast, complex system of people and machines, of which Everson could show only a few fragments. A disturbing history lurks beneath the films’ boilerplate titles: Westinghouse Electric used to be the largest employer in Mansfield, Ohio, Everson’s birthplace, and its departure in 1990 did everything but rip the city apart. Yet the content of the films can be read as a cool rejoinder to this history and its smug assumptions about the workforce. Unskilled labor as performed by Whitfield is made up of a thousand tiny skills, so that, paradoxically, his ironing seems more unique with each repetition until it’s as singular, in its way, as an old master’s brushstroke.

Paintings old and new have left their mark on these works. The spot-the-difference-puzzle approach is borrowed from Rauschenberg’s 1957 Factum diptych (previously an inspiration for Everson’s film Emergency Needs, from 2007), and when asked about his use of high-contrast black-and-white 16mm, which makes Whitfield’s skin almost indistinguishable from the shadows around him, Everson has praised the sinister-yet-emancipatory images of Kerry James Marshall. The enveloping darkness of Everson’s works also evokes the racist history of film lighting and processing, which in some cases diminished black figures on-screen to not much more than eyes and teeth. Here, though, you don’t get the sense that Whitfield is being erased by the camera so much as eluding it, refusing to simplify himself or his actions for the sake of a stranger’s gaze.

All of which points to another ethical/aesthetic question, maybe the central one Everson’s films raise: who are they for? In the past, Everson has said he makes art for his subjects, not his audience, depicting them without giving into the pressure to explain or decode. The results have been challenging but, at their best, equal parts banal and magical—something like what the poet Les Murray meant when he wrote about “an absolutely ordinary rainbow”—though the more appropriate image, from Westinghouse 1, is of plain white cloth that seems almost to iron itself.

[ad_2]

Source link