[ad_1]

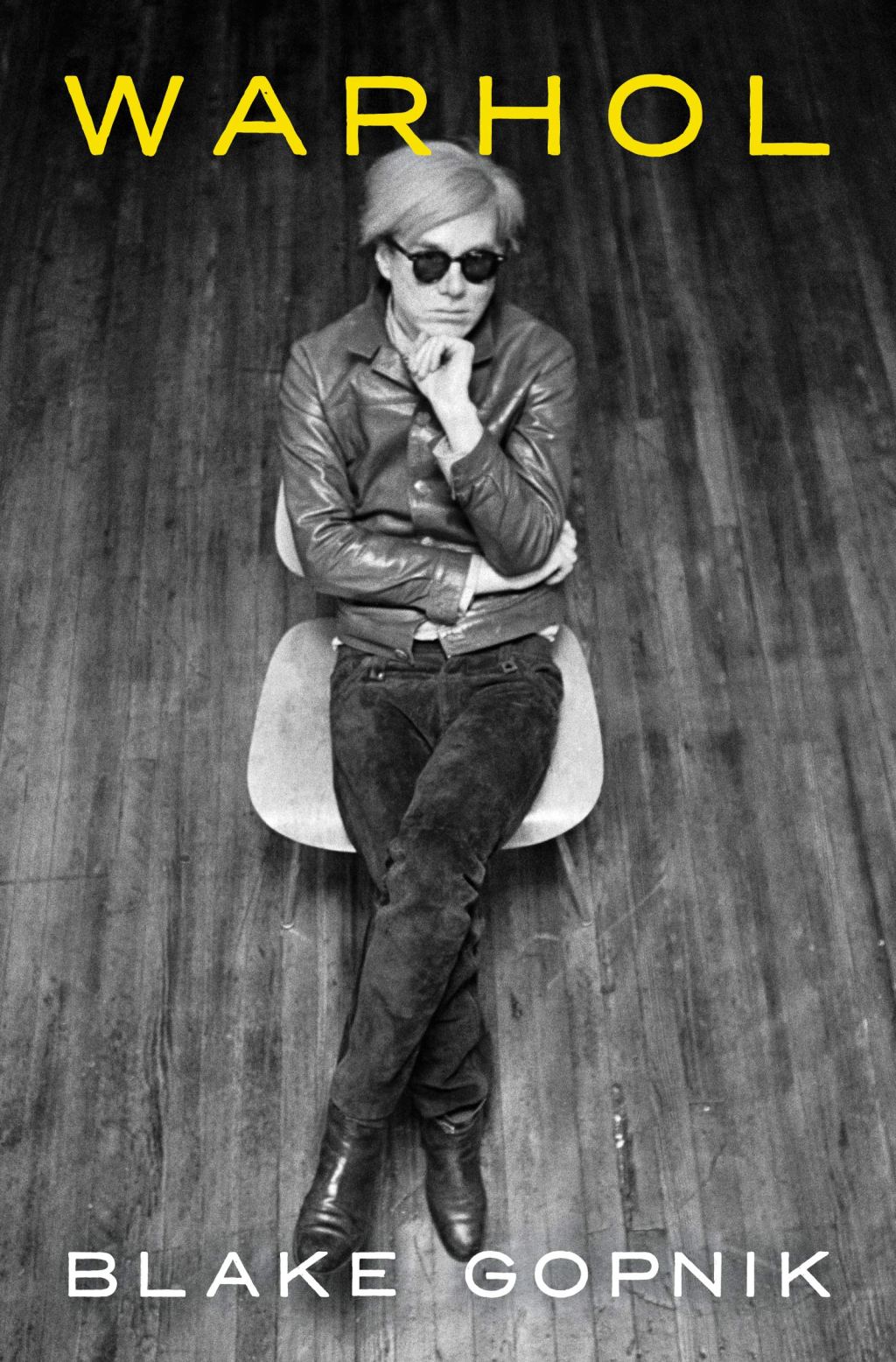

With every major retrospective and every important tome, we get both closer and farther away from knowing the full truth about Andy Warhol. The artist himself worked to obscure his own biography and adopted different personae that changed over the years—all of which Blake Gopnik surveys in Warhol, a new biography published Ecco. The 900-plus-page book covers the scope of Warhol’s life, offering incisive looks at the influence of his upbringing and the role that his queerness played in his art. Of the book’s many pages, only about 200 are given over to Warhol’s Pop years; far more are devoted to exploring lesser-known and understudied parts of his oeuvre.

To learn more about the book and the process of writing it, ARTnews spoke with Gopnik about Warhol’s greatest mysteries and what he learned about an artist who is both so familiar and so elusive at once.

ARTnews: Since Andy Warhol is one of the greatest myth-makers in art history, to what extent did you want to search for the truth behind his biographical details?

Blake Gopnik: Andy is one of the stranger of the figures to have as the subject of a biography because, normally, the subject of your biography is the most reliable source. That forms the backbone of your biography, and then you flesh it out from there. But of course, Andy’s exactly the opposite. He reveled in indeterminacy. In fact, I would argue that is maybe his most important art supply: indeterminacy itself. You are stuck in this crazy situation where you are trying to undo the indeterminacy that he himself was creating in his life and in his art. Having said this, yes, it’s a biographer’s job to get the truth, even when the subject is doing their very best to prevent you from doing that.

How did you conduct your research?

One of the strange things about Andy Warhol is that, though he was keen on myth-making, he also left behind of this absurd amount of information. Not just the famous time capsules—boxes of ephemera—but also vast amounts of financial papers and medical papers, every kind of document you can imagine. In a sense, he made it easier for biographers because there’s so much material to fact-check the myth. I was able to do that, to a large extent.

Many have claimed that Warhol wasn’t exactly an intellectual, but others disagree.

The myth of Andy as illiterate falls apart completely when you realize that he actually read a great deal. His books survive. His correspondence with people who talk about his writings survive. There’s lots and lots of evidence. And his marks sheets from college, his grade-school grades. All that shows us that he was a pretty smart character, despite his intents to portray himself as kind of naïve.

With such a wealth of information available, where did you start with it?

It was hard! There was simply too much information. Not only were there thousands of documents that Andy himself saved—then there are unbelievable amounts of articles about him. Once he became famous, he was written up in ever goddamn newspaper across the country. Every magazine wrote features about him.

I mostly proceeded chronologically. I did my best to look at all the documents in the archive from a given year. They’re not all inventoried, so there is a hit-or-miss quality to it all. I can’t say that I looked at every single document in the Andy Warhol archives because the book was going to take me 100 years to write.

Were there any finds in particular that surprised you?

I didn’t only do research in his own archives. I worked in archives all across the country, and one of the most rewarding was the most rewarding things was going through the archives at Carnegie Mellon University [in Pittsburgh, where Warhol went to school from 1945 to 1949] and finding the lecture notes of his teachers. It was incredibly interesting because it turns out that the art department was best in the country at that particular moment. He had a really fantastic avant-garde education. It was a little golden age for when he was there, and he really profited from it. The students were doing experimental cinema in the ’40s! They knew about Dada, they knew about Duchamp. They knew John Cage—he appeared several times in Pittsburgh. So they really were on the cutting edge of culture at that moment.

You take a great deal of interest in works Warhol experienced early on and draw parallels with his later life and work. How did you about making those connections?

It’s always risky—it’s always possible to see connections where there aren’t any. But there is evidence from Andy’s friends that he had a particularly powerful memory—he was great at retaining things—so it doesn’t seem far-fetched. I was particularly struck, in his early life up to his college education, with the issues around gender and homosexuality. I dwell in the book a lot on what it was like to be gay and to come out as gay in Pittsburgh in the 1940s. Andy’s sexuality is essential to everything he did, and it formed in Pittsburgh. I have no doubt in my mind at all that understanding that formation as a gay man is essential to understanding almost everything he did. And it so happens that Pittsburgh was just about the worst possible place to be gay in North America and, at the particular moment that Andy was coming out, his sexuality was absolutely salient.

You repeatedly stake a claim for how queer culture and matters related to gender and sexuality impacted his work, whereas these have been downplayed in the past.

One of the most important things was to emphasize the fact that he was sexual. There’s a myth of his being asexual, which he propagated himself. He wasn’t voracious, sexually. But he clearly had a sexual life, certainly up to when he was shot in 1968. After that, his body was so damaged that it wouldn’t be surprising if sex became a little less interesting to him. He didn’t live with a man for 12 years after being shot.

I do wonder if one reason we accept the notion that he was asexual is that, though in 2020 we accept homosexuality in theory, I think the straight world has a real problem with the notion of two men in bed having sex. We prefer a generic notion of gay culture than a stronger notion of two men having sex, so we paper over Warhol’s real sexuality or his overall sexual identity. It was important for me to establish that he was a normal sexual human being.

One of the things I wanted to establish in the book is that, for a freak, he was more normal than we imagine. He was a normal freak, the way we are all normal freaks in one way or another. He loved and he was romantic. He did his best to have boyfriends. He wanted a lot of the things the rest of us want and fail to get. He didn’t have an easy life. Growing up gay in the 1940s in Pittsburgh isn’t going to make anyone have a stable psyche.

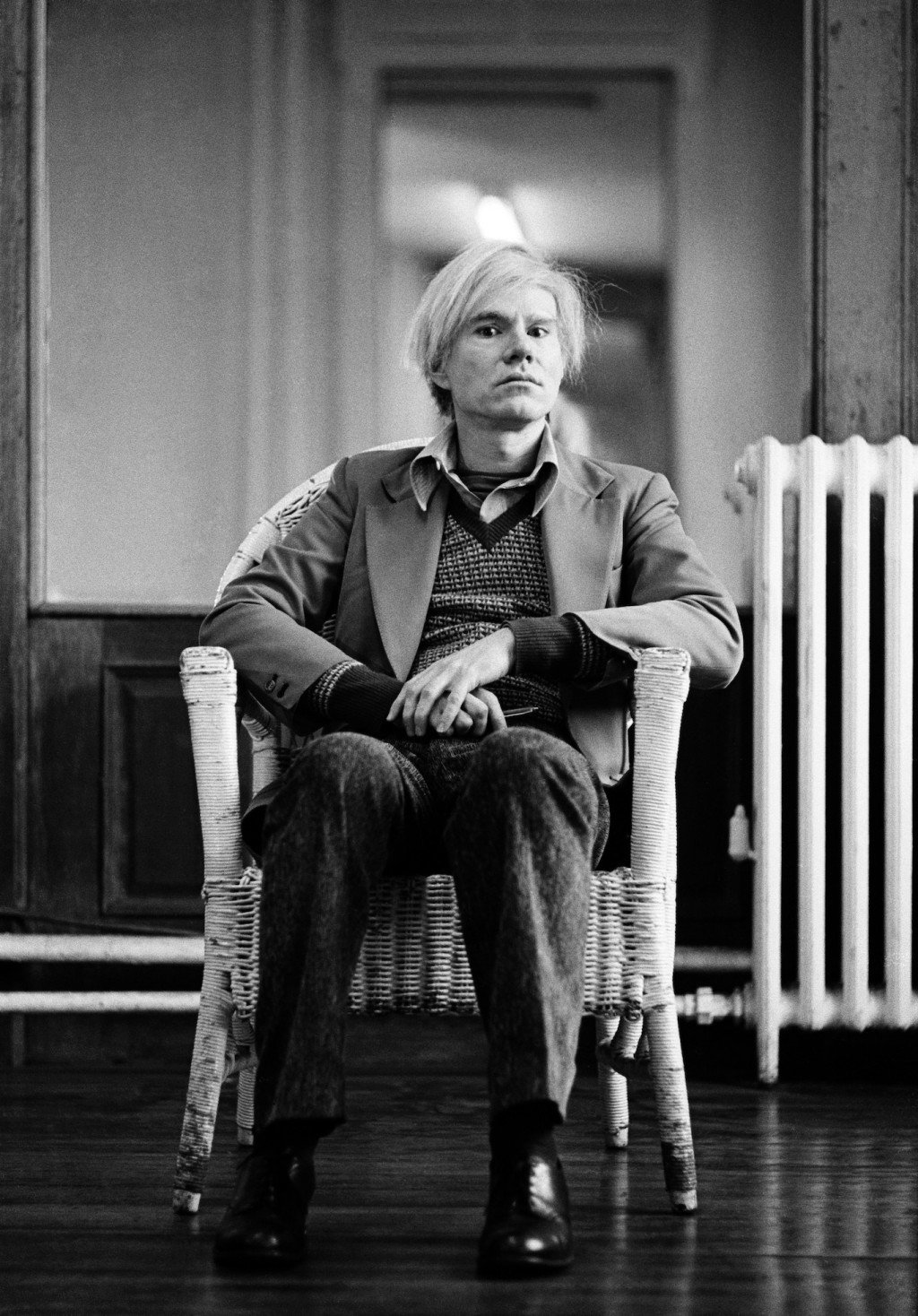

Globe Photos/mediapunch/Shutterstock

Warhol’s impact as a filmmaker has been understated by some. How do you regard it?

His films are probably now among the least understood of his works, even though it’s important to say that for a good chunk of his career, he was understood as an underground filmmaker more than anything else. When he was shot, some of the newspaper headlines say “Underground Filmmaker Shot.” They don’t say “Pop Artist Shot.” His identity was completely wrapped up in filmmaking for maybe four or five years, and then that was lost track of, and he became, once again, Andy Warhol, Pop artist. The films are just stunning, especially the earlier films from ’64, ’65, ’66.

You claim throughout the book that he was a more political artist than many have seen him to be. Why do you think there is so much misperception of that?

All his work, and this is really important, is indeterminate. He doesn’t lay all his cards on the table. He doesn’t say, “Look at this, folks. This is political.” He doesn’t fling messages. It’s much, much more subtle than that, so it’s easy not to notice the politics in. But it is important to notice that, from the beginning, when he first was doing the Pop art—the Campbell’s Soup Cans, etc.—they were seen as an attack on American consumerism, not a celebration of it. His very first written statement about Pop art bills his own work as an attack, more or less a critique of American consumer culture, so that was there at the beginning and then gets lost as Pop art becomes part of popular culture. As it becomes popular in the mainstream, he backs off from his reading of it as critique, but all the good critics read it that way, and he knew some of the smartest critics of his era.

You go through his papers, and there are tons of thank-you notes from leftist causes. There are no thank-you notes from right-wing causes! That’s a simple statistical measure of where his politics lay. Now, he was not a deeply political person. He was signing petitions from a young age, but he wouldn’t go much further than that. He wouldn’t organize demonstrations or anything like that. He was an artist consumed with making art, but he definitely was on the left edge of American politics, there’s no doubt about that. You couldn’t be an out gay and be conservative. In the 1960s, it just wasn’t possible—you wouldn’t be accepted.

What were some of the leftist causes that had thanked him?

There were feminist causes that supported him. He supports McGovern [George McGovern, a Democratic U.S. senator who ran against Richard Nixon for President in 1972]—you can’t get much more straightforwardly left-wing than that! He makes a poster for McGovern. He supported Bobby Kennedy. He was much more involved than people realized in AIDS fundraising than people realize.

Some suggest that everything Warhol produced after the 1960s wasn’t as good as everything he produced before. Do you think that’s starting to change?

Oh, definitely. It’s been changing for a good 20 years now in academia, but it’s taken that a while for that to sink in with the public. Weirdly, he’s still Andy Warhol, Pop artist. He really was a Pop artist for about three years. By 1965, he said, “I’m abandoning Pop painting for filmmaking.” And you can’t really call his films Pop films—they’re experimental and extreme, but they’re not Pop by any means. He was a Pop artist for three years, and he was a practicing artist from 1960 to 1987, so 27 years of being a practicing artist, of which only a little bit is Pop.

He made a lot of bad work at the end—some terrible paintings, a lot of “Society” portraits that are mixed at best—but he also made some really fascinating work. The “Camouflages,” the “Piss paintings,” the “Rorschachs”—there’s a lot of really good late work. There’s a lot of works—people don’t realize this—that are performances, truly conceptual works, and we completely lost track of Warhol, the dedicated conceptualist. When his Pop work first came out, it was seen as being totally conceptual, as having no formal values whatsoever. Conceptualism mattered to him. He collected this stuff—he collected Joseph Kosuth, he collected Les Levine. He was deeply interested in conceptualism, and he made purely conceptualist work himself. He planned even more than the ones he made.

Stephen Chung/LNP/Shutterstock

When you were doing research, was it difficult to get people to talk?

Very rarely. There were people who were too old to speak. One problem was that there were people who’d been interviewed a million times, and they just rehashed the same stories. It’s almost impossible to get them to access their memories, rather than the stories they’ve already told. I much preferred interviewing the people who’d never been interviewed before—the minor figures in his life. I got much more out of them, mostly, although Gerard Malanga [a Warhol collaborator and romantic partner] was hugely helpful—I spoke to him for hours and hours.

One person slammed the door in my face: Warhol’s collaborator in film, Paul Morrissey, screamed at me so loudly on the telephone that I actually had to end up putting down the receiver. But other than that I had very few problems.

What do you hope people will learn from the book?

I want them more than anything else to realize that he’s a true, normal artistic genius—or as normal as artistic geniuses get. That means he’s on the order of Picasso or Pollock or van Gogh, all of whom were first foremost artistic geniuses. Their idiosyncrasies—their lunacy, even—are absolutely secondary to their art. The art itself is deeply intelligent at every moment, and it comes from a deeply fascinating and complex and intelligent mind.

Do you have favorite work by Warhol?

There’s no getting around the Campbell’s Soup Cans. It’s a cliché, but it’s amazing how early in his career he comes up with these amazing objects. I spent hours and hours looking at those 32 Campbell’s Soup Cans that he first showed in 1962 in Los Angeles [at Ferus Gallery], and I never come to the end of them. They’re incredibly fertile. Having said this, I do think the films are absolutely stupendous works of art. I have sat with Empire [1964] for all eight hours, watching the Empire State Building, and I didn’t grow tired of it for one minute. It was hugely generative as a work of art. How about if I also tell you about my favorite moment in the book?

Please do.

In Chapter 13, there’s an incredible moment where Andy puts his Pop paintings into a window at Gunther Jaeckel’s department store [Bonwit Teller]. My argument is that they’re not Pop art paintings yet. They’re simply window props. And what happens is, he has a eureka moment shortly after having received them back from the window and realizes, “Wait a minute, those things I made as commercial props to sell young women’s clothing could double as art.” He turns them into a readymade. He holds them up on the pedestal as art—it’s that Duchampian moment that changes everything.

[ad_2]

Source link