[ad_1]

By turns spectacular and taciturn, “The Allure of Matter: Material Art from China” presented viewers with an inordinate number of substances. Installations featuring familiar materials, such as pulped paper, concrete, and wood, shared the galleries with artworks employing silkworms, gunpowder, and resin from boiled Coca-Cola. The range of mediums produced jarring shifts in mood and tone: in Chen Zhen’s Crystal Landscape of Inner Body (2000), glass sculptures of human organs glisten on a table like the remnants of an autopsy, while in Zhang Huan’s drawing Seeds (2007), a pastoral farming scene rendered in incense ash projects quiet intensity. Despite their differences, the forty-eight works by twenty-six artists were connected, somewhat tenuously, by the curatorial premise that since the late 1980s, a dominant group of Chinese artists has allowed material choices to drive conceptual inquires.

After its initial run at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, “The Allure of Matter” arrived in Chicago, where, owing partly to the large scale of many works, it was split between two venues: Wrightwood 659, a Tadao Ando–designed gallery space in Lincoln Park, and, on the opposite side of the city, the Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago.

Wu Hung, an art history professor at the university who organized the exhibition with Smart curator Orianna Cacchione, coined the term caizhi yishu, or “Material art,” to identify an area of contemporary Chinese art that he argues is largely unexplored—a somewhat surprising claim, given that some of its practitioners, including gu wenda, Xu Bing, and Ai Weiwei, are counted among the most prominent artists working today. In his catalogue essay, Wu describes how Material art is the culmination of a rush of creative energy in the last decades of the twentieth century, as experimental artists sought to make up for time lost under the rigid constraints of the Cultural Revolution. After Mao’s death in 1976, Chinese artists had new opportunities to travel abroad, and there was an influx of previously unavailable translations of Western literature, philosophy, and art criticism. In contrast to the 1990s painting movements Political Pop and Cynical Realism—the first of which ironically recast icons from the Maoist era as commercial items, while the second applied canned antihero figural tropes to Chinese culture—Wu offers Material art as “a thoroughly cosmopolitan approach within contemporary Chinese art and a culturally informed regional approach within global contemporary art.” Rather than creating pictorial signifiers of Chinese identity, the resulting works “‘distill’ essential substances of traditional material culture . . . transform[ing] such shared cultural properties into a personalized visual language.”

To identify a collective tendency underlying highly individualized practices, the curators constructed a taxonomy rather than a chronological overview of an artistic school. Many Material artists, for example, maintain a critical relationship with painting and other traditional art forms. Cai Guo-Qiang’s large-scale work on paper Mountain Range (2006) appears as delicate as a watercolor or gouache painting, belying the violence required to make it. A video across from Mountain Range showed the artist’s method of distributing gunpowder over his designs, placing fuses, and then covering the work and detonating the explosives. Liu Jianhua creates installations out of fine porcelain, a material so embedded in the history of China that, at least in the West, it is synonymous with the country. At the Smart, three porcelain sheets as thin as loose-leaf pages hung on the wall (Blank Paper, 2009–12). Invoking the tradition of monochrome painting, the work seemed to invite viewers to project their own ideas about “china.” The subtle, powerful piece provided a dramatic contrast with the artist’s floor-based installation at Wrightwood: Black Flame (2017), comprising eight thousand porcelain objects that resemble flames. Visitors tiptoed around the exquisitely fragile work as if avoiding open fire.

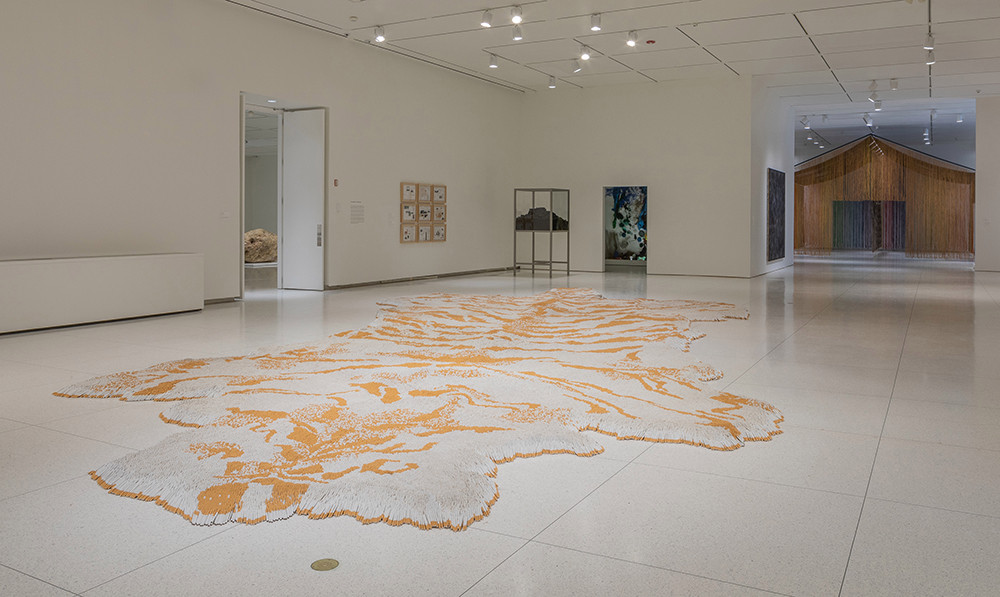

While Wu and Cacchione acknowledged 1960s precedents like Arte Povera in Italy, process art in the United States, and Mono-ha in Japan, they avoided an overarching East-West dichotomy, preferring instead to examine global dialogues through specific works, an approach exemplified by the presentation of Xu Bing’s work at the Smart. Tobacco became an important medium for the artist after he received, in 2000, a commission from Duke University, where he researched the school’s historical ties to the tobacco industry, which generates massive revenue selling cigarettes in China. Xu’s 1st Class (2011), an installation resembling a tiger-skin rug but constructed out of some half-million cigarettes, emitted tobacco aromas that wafted through the space. A glass case nearby contained a related work: Traveling Down the River (2011), a facsimile of a Song dynasty hand scroll marked by a long trail of cigarette ash. Displayed in another case was Tobacco Book (2011), for which Xu printed English text describing the expansion of the American Tobacco Company in China on cured tobacco leaves that had been ravaged by beetles.

If Xu’s work was a subtle investigation of material culture, other pieces in the show were geared toward sensational material effects. Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s 2001/19 sculptural column rendered using human fat extracted via liposuction relies on its title, Civilization Pillar, to convey a critical perspective. In a similar vein, gu wenda’s united nations: american code (1995–2019)—a tent constructed entirely of ropes of human hair dyed in rainbow colors—uses bodily remains to give an aura of authenticity to a vision of transnational togetherness.

The uneven applicability of the Material art premise to the works on view spoke to the curators’ refusal to choose between the prescriptive (“This is what Material art is”) and the descriptive (“This is what Material artists make”). Wu and Cacchione wanted to stress the individuality of each artist’s practice while simultaneously advancing a new historical category that’s at once in dialogue with global trends and distinct from Western contemporary art. The resultant confusion in the exhibition clouded an otherwise laudatory effort. Liang Shaoji’s Chains: The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Nature Series, No. 79 (2002–07) is a group of hanging chains that look ghostlike, having been coated with fibroin produced by live silkworms. Wang Jin uses plastic sheets to construct reproductions of Qing dynasty imperial robes and traditional opera costumes. To characterize the two projects as part of the same phenomenon serves to obscure their core differences. Liang is essentially a steward; having removed himself from the equation, his material constructs the work as his proxy. Wang actively imposed a position and deployed his material to support his case. They both “use” materials, but only the former appears to be driven primarily by its allure.

One gets the sense that the phrases “Material Art” and “from China” in the show’s subtitle are almost at odds with each other. An emphasis on materiality might have been better elucidated by comparisons with Western and Japanese counterparts. Or a pivotal era in Chinese art could have been defined more sharply with historical context. Regardless, “The Allure of Matter” challenged visitors to see the diversity and range in the works on view. Further, hardly content with merely documenting Chinese practices for a Western audience, the curators offered an aesthetic argument that, however muddled in places, appeared to transcend national identity as well as issues of representation.

This article appears under the title “’The Allure of Matter’” in the April 2020 issue, pp. 73–74.

[ad_2]

Source link