[ad_1]

Floris Neusüss, a photographer whose cameraless pictures feature ghostly silhouettes and mysterious presences, died on April 1 in Kassel, Germany, at the age of 83. His death was confirmed on social media by the Los Angeles-based Von Lintel Gallery, which has represented Neusüss since 2013 alongside London’s Atlas Gallery.

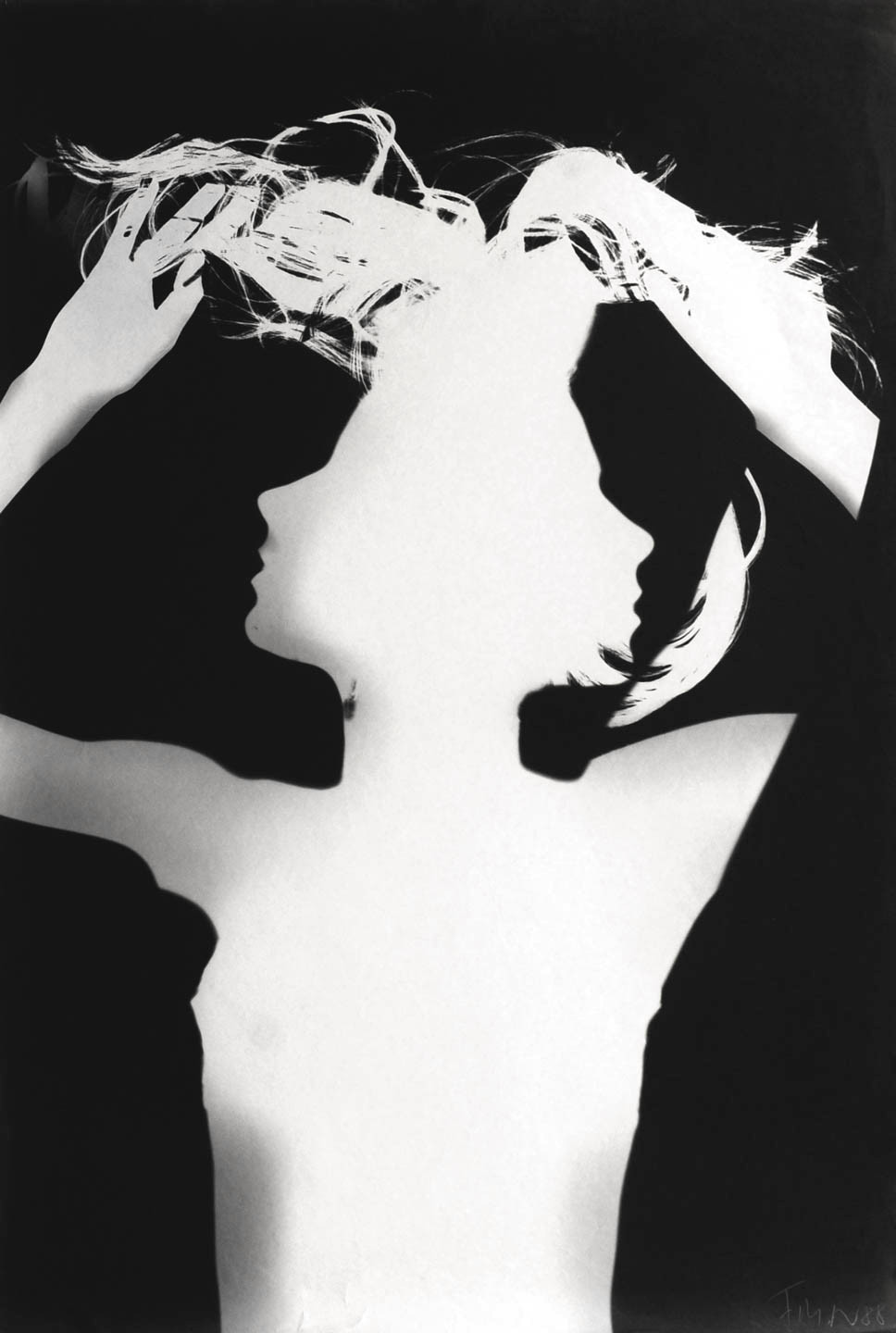

Born in 1937 in Lennep, Germany, Neusüss has been considered a pioneer of cameraless photography, most notably for his photograms, which involve placing objects and people directly onto photo-sensitive paper and exposing the surface to light. Utilized memorably in the first half of the 20th century by artists such as Christian Schad, Man Ray, and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, the photogram process allowed Neusüss to go beyond the visible world as it appears to the naked eye.

“A photogram produces a feeling of mental unease by subverting familiar visual patterns like perspective and turning the visual space on its head,” he told the Telegraph in 2010. “Photography works as a comfort, as Man Ray said, because it reproduces what is known. The photogram denies the observer this immediate familiarity and perhaps for that reason, it’s difficult for it to find popular success.”

Neusüss’s most famous series, the “Nudogramms,” produced in the 1960s, feature nude women’s forms that are rendered in semi-translucent states, causing them to look like specters. Over the course of his career, his subjects ranged widely—he made photograms from the body of artist Robert Heinecken (who himself produced photograms), a window in the home of photographer William Fox Talbot, and a sculpture by Antonio Canova, to name just a few.

His photograms are currently held in the collections of the Art Institute of Chicago, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, among others, and were shown prominently at London’s V&A museum in 2010.

While photograms differ from the way we typically see the world, Neusüss insisted that they got at something more accurate to life than regular photography ever could. “Certainly the image a camera produces is much closer to how the human eye sees, perhaps too close even,” he told the Telegraph. “That’s why photographs are often taken for true, when they are authentic at best.”

[ad_2]

Source link