[ad_1]

When we watch from our laptops and televisions at home, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo’s daily coronavirus briefings always float atop a background of cobalt blue. Two thick goldenrod lines cut horizontally across our screens, boxing in a diptych: a video feed of Cuomo to the left, his PowerPoint slides to the right. Sometimes, he appears in a navy suit and tie; other times, in a white polo shirt emblazoned with the New York State logo. When the camera cuts wide, we see his aides and other state officials sitting the requisite six feet apart at an exceptionally long table.

Mike Groll/Office of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo

These briefings take place in the Executive Chamber of the New York State Capitol Building in Albany. Behind the panel of speakers are the mahogany-paneled, gold leaf–ornamented walls of the so-called Red Room, designed by noted nineteenth-century architect Henry Hobson Richardson (namesake of the Richardson Romanesque style). Stained-glass arches crown Palladian windows, their heavy green and red curtains drawn tightly closed. Watching the briefings from our own modest couches and office chairs, we occasionally catch glimpses of the coffered oak ceiling and chandeliers that hang over the press corps’ heads. Cuomo centers himself between the state and national flags, just beneath a bronze relief of the New York State seal, in which two female figures, Liberty and Justice, flank a Hudson River scene. An eagle with spread wings is perched above them.

The room’s opulence is interrupted by two glaring blue screens displaying Cuomo’s slideshows. Yet this ungainly equipment also serves to connect our worlds to Albany, linking our own tiny blue screens to the two big ones in the Red Room. At the same time, Cuomo’s screens serve as portals to a different aesthetic universe, bridging Richardson’s stately grandeur and a new digital, managerial manifestation of institutional authority. At a time when national “leadership” is embodied by ill-fitting suits and garish Fox News graphics, Sharpie-edited maps and Mar-a-Lago chintz, Cuomo’s briefings and their centerpiece slides have captured national attention by cultivating an image of accountability, credibility, and empathy (even if, as the New York Times recently reported, New York’s leaders might have botched their response to the coronavirus crisis).

Cuomo has long been known for his “bulldozer personality” and his tendency toward micromanagement, as evidenced in the notoriously exhaustive PowerPoints that have accompanied nearly all of his major speeches as governor. His briefings, delivered from the current epicenter of the viral crisis, now offer at least a simulacrum of competent leadership. At the same time, his presentations “capture an everyman’s emotional unease,” according to the New York Times. In another article, the paper’s media columnist called him “the control freak we need right now”—one who knows his way around the government and can translate public health and public policy into intelligible terms, yet also, like us, fears for his family’s safety and laments the inefficiencies of political process. Marshaling PowerPoint, that ubiquitous platform for urgent didactic and persuasive communication, his performance-lectures—“part briefing, part sermon, part inspirational talk,” per the Washington Post—are our primer, pep talk, and placation.

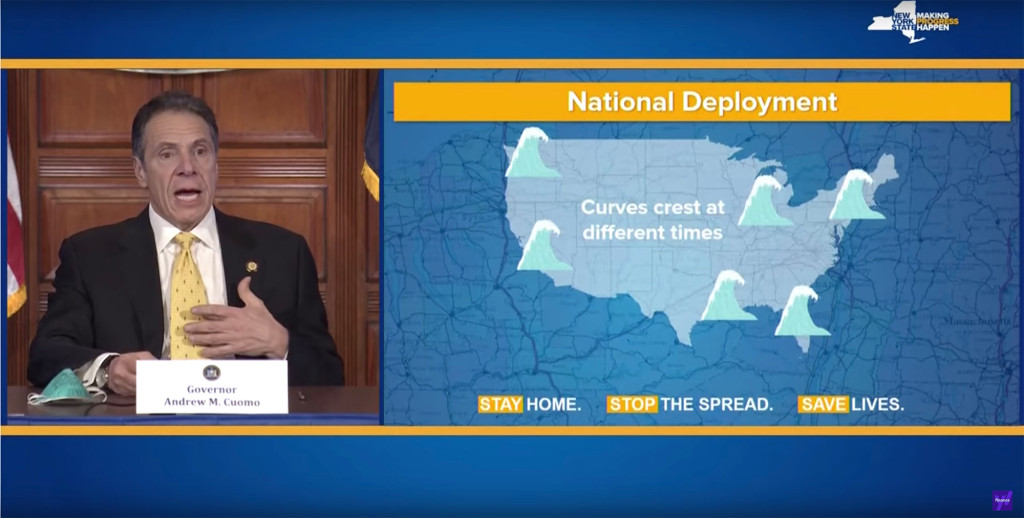

A blue-tinted stock or news photo—of gloved hands, hospital workers, or city scenes—typically serves as a muted substrate for the slides’ factual content. New York State branding guidelines stipulate that photography used in official communication be authentic, inspiring, dynamic, and compassionate. Cuomo’s photos deliver; they provide the underlying pathos, while the bullet-points and bar charts layered on top appeal to logic. Rudimentary tables and maps adhere conscientiously (if, at times, inelegantly) to best practices for information design, as well as the state’s official blue-and-gold color scheme. Yet the slideshows also occasionally incorporate whimsical clip art: cresting waves signal peak infection, for instance, while chunky arrows remind us that we want to “flatten the curve.”

The slides’ body text appears in a no-nonsense white sans serif typeface—typically Arial, in accordance with the state’s graphic standards. Arial also happens to be a standard font for Microsoft, maker of PowerPoint, which might partly explain its prevalence. But when the Governor’s message is meant to be inspirational or profound, the typesetting is more dramatic—centered with lots of leading, or space between lines—and words often manifest in a friendlier, crisper font: Proxima Nova. Workaday Arial comes in only two flavors: bold and regular. Its graphic limitations compel Cuomo’s slidemakers to play with other expressive variables—specifically color. Key terms and takeaways—often chosen according to elusive criteria—are set in gold. That same gold color is used to highlight the alliterative imperatives in a footer at the bottom of most slides: “STAY HOME. STOP THE SPREAD. SAVE LIVES.”

In spite of the purported bureaucratic blandness of PowerPoint’s bullet points, Cuomo manages to infuse his slide text with dad-like concern and (inadvertent) comedy. “Younger People Not Fully Complying” with social distancing guidelines, one slide declares: “YOU ARE WRONG.” He’s yelling at us. After noting flagrant violations by youngsters in New York City’s parks, the slide’s final bullet-point announces: “I am going there today.” Watch out, kids. Another slide displays a photo of vibrant socializing and commercial exchange at the Grand Army Plaza greenmarket—a scene that, in normal times, would emblematize the best of Brooklyn. Yet here the scene is superimposed with a big red, all-caps, officiously Arial “MISTAKE.”

His slides mix impersonal factual delivery with second-person exhortations, first-person declarations, and philosophical introspection. One slide reminds us: “Today is Saturday,” with “Saturday” emblazoned in gold. This statement of truth is accidentally hilarious in its self-evidence. Another delivers a message to Cuomo’s fellow Democrats, whom, he says, are reluctant to criticize one another: “Baloney”—a spare declaration warranting its own bullet point. Yet another minimalist slide informs us that, whether we like it or not, “This will be a transformative experience.” Another headlined “What Happens” prompts Cuomo to note, in Proxima Nova, that the “Bigger Question to Me” is “WHAT DO WE LEARN ABOUT OURSELVES?”

The lessons we might derive from such introspection are framed, in part, by the mix of civic symbols encountered in these briefings: Richardson’s excess and Microsoft’s functionalism, regal hues and high-contrast blue and gold, state flags and clip art, velvet curtains and polo shirts, chandeliers and LCD projectors. Cuomo deploys the aesthetics of authority old and new: he draws on the resonance of long-standing material symbols of civic strength and the tools of twenty-first century technocracy, as if to acknowledge the need for new emblems of trust and accountability in an age of digital transformation and political division. In contrast to the buffoonery masquerading as leadership in the White House at a moment that necessitates the full mobilization of the government, Cuomo’s slideshows project a reassuring image of managerial order—one that has arguably distracted from his missteps, such as the delay in implementing social distancing measures and closing non-essential businesses. Still, the motley aesthetic of Cuomo’s briefings mirrors our own confusion and disorientation—our uncertainty about how to spend our days trapped indoors, about which sources to trust, and about the proper role of the state and its institutions at a time when our immune systems, our public health infrastructures, our electoral politics, and capitalism itself reveal their terrifying precarity all at once. WHAT DO WE LEARN ABOUT OURSELVES, as individuals and as a nation, is still an open-ended question. But the bar charts and bullet points at least offer a provisional ground—stable, rational—from which we can continue our investigation.

[ad_2]

Source link