[ad_1]

The expression of “When white America gets a cold, Black America gets the flu” has always rung true, but for many people, rarely has it resounded as significantly as it has during the coronavirus pandemic.

This expression has shifted from words to reality, time and again, with stark disparities in education, housing, voting, employment, healthcare, and the criminal legal system.

The flu became even more pronounced when two Black men were kicked out of a Nashville Walmart for wearing protective masks — a recommendation by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (and mandated in some cities and states) to slow the spread of this public health crisis.

READ MORE: Black men told to leave Walmart for wearing masks

And with recent race-based data showing the percentages of infections and deaths in communities of color compared with those who test positive or die from COVID-19 in white communities, a troubling truth has emerged: structural racism has turned the flu into a death sentence for many Black Americans.

Recently, Senator Elizabeth Warren and Representative Ayanna Pressley urged the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to collect and publish racial demographics of the people who are being tested for, infected with, hospitalized with, or killed by COVID-19. Local leaders and editorial boards like the Baltimore Sun are pushing for the same.

The data we now have is clear: Black Americans are dying more from COVID-19 than any other population.

READ MORE: Coronavirus is hitting Black America at a staggering rate

In Chicago, even though the city’s population is just 30 percent Black, a recent report found that 70 percent of people who died from the virus are Black. Detroit, where Black people make up 80 percent of the city’s population, has significantly increased Michigan’s overall death rate by 40 percent. In Milwaukee County, which is just 27 percent Black, 81 percent of those who test positive are Black.

The picture in the South is no less grim. In Louisiana, Black people comprise more than 70 percent of COVID-19 deaths in a state that is approximately one-third Black. Roughly 33 percent of the state’s 512 deaths have occurred in Orleans Parish where Black people make up more than 60 percent of the population. Public health officials tracking the coronavirus have seen similarly disproportionate impacts on Black Americans in other cities and states.

That’s not because of race, but racism. The distinction matters.

READ MORE: Lousiana’s COVID-19 deaths were 70 percent Black residents

If we’d let social media tell it, young Black people are testing positive compared to other communities because we are socially distancing less in an effort to have fun with our friends and loved ones. While this may be true for a very small subset, this argument goes out the window when we understand the mental, physical, and emotional harm inflicted by structural racism — especially in healthcare.

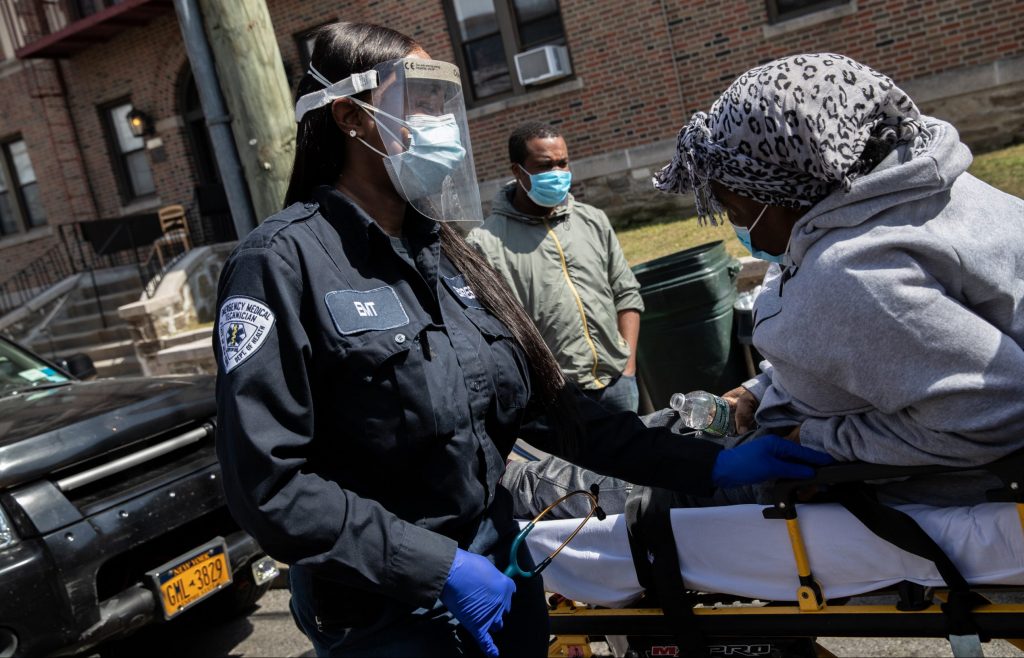

Black communities are not intentionally socially distancing less than other communities. Those who work essential jobs or are in the gig economy are disproportionately Black. For these communities, social distance is a privilege reserved only for those who can do so while still earning a living.

Essential workers put their lives on the line and are often unpaid. They are not just nurses, doctors, and firefighters — they are also janitors, home health aides and social workers, Uber and Lyft drivers, grocery store employees, fast food workers, and package handlers. These jobs require more in-person contact. In most cities, low-wage and essential workers are people of color and are particularly susceptible to the devastating health impacts of COVID-19.

Black communities (and Black queer families, especially) live in the south where states have not expanded Medicaid access. This dramatically impacts our access to health care. According to Kaiser Family Foundation, “the South has relatively higher numbers of poor, uninsured adults than in other regions, has higher uninsured rates, and more limited Medicaid eligibility than other regions, and accounts for the majority (9 out of 14) of states that opted not to expand Medicaid.”

READ MORE: LGBTQ community uniquely impacted by COVID-19, research shows

As a result, more than 9 in 10 people that fall within the coverage gap reside in the south.

Experts also underscore initial research showing a high prevalence of COVID-19 among those experiencing pre-existing conditions. Studies have shown this is largely due to the fact that people of color often live in food deserts and receive lower quality life-saving and preventive medical care.

This is to say nothing of the rampant environmental racism; unemployment and underemployment; housing instability, and criminalization that Black communities have experienced for generations. A global health pandemic coupled with a haphazard healthcare system creates a perfect storm for structural racism to exact its deadly toll.

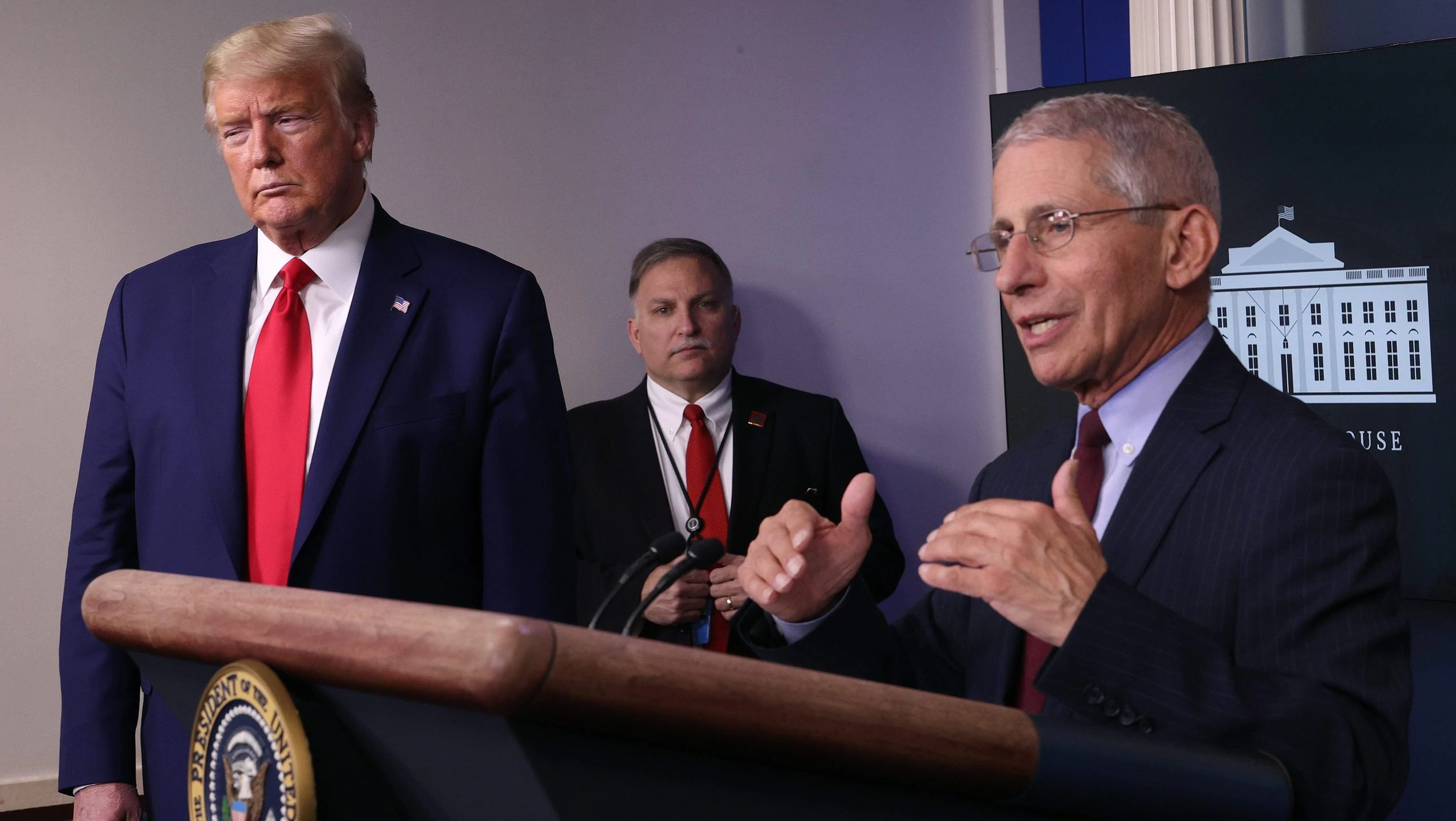

As Dr. Anthony Fauci, the global health expert who sits on Trump’s coronavirus task force, made it clear at the White House press conference on Tuesday: “It’s not that (Black Americans) are getting infected more often, it’s that, when they do get infected, their underlying medical conditions…wind them up in the ICU.

He added, “Public health officials have known that conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and asthma disproportionately affect African Americans. Unfortunately, when you look at the predisposing conditions that lead to a bad outcome with coronavirus, the things that get people into ICUs that require incubation that often lead to death, they are just those very comorbidities.”

These problems are particularly pronounced at the intersection of race, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, and poverty as we know LGBTQ+ people of color are more likely to lack health insurance coverage, have asthma, smoke cigarettes, live in poverty, and be criminalized. Each factor has an impact on contracting COVID-19.

As such, local and state governments must consider proactive policy solutions, not carceral practices that instill fear and panic. As mayors and governors issue stay-at-home orders, many have attached criminal penalties on those who do not comply and the severity of enforcing these is quite alarming.

From Kansas City, Missouri’s stay-at-home order to Mecklenburg County, North Carolina’s joint proclamation to the order in my current home in Maryland, lawmakers in each have proposed or warned of a fine, misdemeanor charge, or other criminal penalties for those who violate stay-at-home orders.

Concerns around enforcement are particularly salient for Black Americans, other people of color, and other system-impacted communities (e.g. incarcerated folks, LGBTQ+ people, and sex workers) that have experienced overcriminalization and arrests as the primary response to substance use and mental health emergencies, among other health issues.

Criminalization itself is a public health crisis and is deeply rooted in the fabric of the United States. Calling law enforcement on people who violate stay-at-home orders — intentionally or not — is not a solution. Arresting and jailing people from marginalized communities will not flatten COVID-19’s curve. Instead, it will put people who are at high risk together and will only serve to spread the virus further.

COVID-19 has displayed a very bright light on the structural racism Black Americans have experienced for centuries. We desperately need to get to the root of the public health disparities we see every day in communities of color — especially in Black communities.

Because once the COVID-19 curve is flattened, young folks from Black communities will still face the same unnecessary barriers to quality health care that sickened and — in many cases — killed their parents and grandparents.

Without reforming these structures, the burden will continue to fall to individuals who must work with incredibly limited resources and little support to find a cure for a deadly flu caused by their own country’s institutions.

Preston Mitchum is the Director of Policy with URGE: Unite for Reproductive & Gender Equity. URGE is a multistate reproductive justice organization powered by young people in the South and Midwest.

[ad_2]

Source link