[ad_1]

Edward Hopper’s paintings—distinctly American, according to many; deeply intriguing, to many more—are full of mysteries. But the questions surrounding Hopper need not be limited to his art alone. How did he get to be famous? What spurred on his most iconic tableaux? A guide that answers these questions—and more—follows below.

He was interested in states of “moving on.”

Hopper’s paintings typically feature people who appear to be standing or sitting still, contemplatively staring outward, though it’s possible that more motion is taking place than initially meets the eye. He described his art as capturing states of “moving on”—going from one place to another. In his 1939 painting New York Movie (on view earlier this year at the Museum of Modern Art in New York), he captures a dramatically lit image of a woman standing in an aisle while a film is screened for a captive audience. She stands by idly, and it’s possible that, seconds after the instance depicted, she rejoins the screening.

He learned from the best.

Although Hopper often claimed greater inspiration from famous Frenchmen of his day—in particular Édouard Manet, whose stylish and occasionally controversial paintings focused on modernity’s impact on social mores—he studied at the New York School of Art with some of the best American artists working at the time. Among them was William Merritt Chase, whose educational center ultimately became the Parsons School of Design in New York. Chase told his students, “Do not try to paint the grandiose thing. Paint the commonplace so that it will be distinguished.” Although Hopper went on to do just that, he said he wasn’t influenced by Chase.

He self-consciously cultivated himself as an art star.

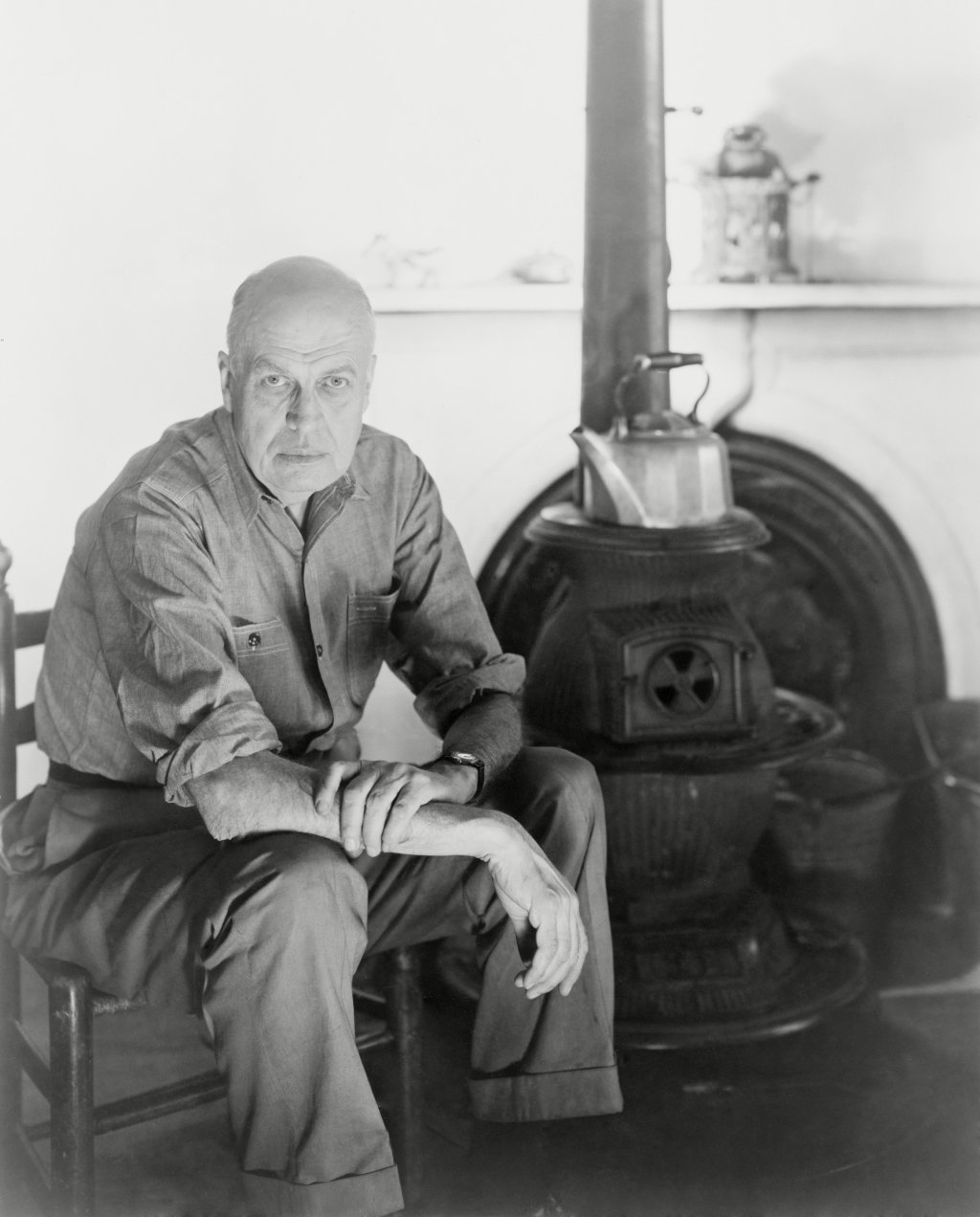

Long before there were art-world celebrities like Jeff Koons and Andy Warhol, there was Edward Hopper. At a time when artists were less focused on PR, Hopper was carefully working his personality. “The critics give you an identity,” he once said. “And sometimes, even, you give it a push.” His main focus became developing a sense of “Americanness” through his art and his strong moral code—aspects that the mid-20th century’s most important photographers, including Berenice Abbott and George Platt Lynes, tried to draw out in their portraits of him. These elements of his persona must have proven attractive, as he was labeled a “newspaper personality” by the press in the later part of his career.

James Gourley/Shutterstock

His market had virtually flatlined early in his career.

Today, Hopper may be considered a market superstar—his 1929 painting Chop Suey, long considered to be the most famous piece by him in private hands, fetched $91.9 million when it hit the auction block at Christie’s in 2018, placing it among the most expensive American artworks ever sold—but that wasn’t always the case. Hopper struggled at the start, and he didn’t sell a single work of art until 1913, when an oil painting of his sold for $250 at the Armory Show in New York. To make ends meet, he taught art classes in Nyack, New York, where you can visit his family home.

Pulp fiction and film noir may have influenced Hopper’s moodier works.

In 1927, after Scribner’s magazine published “The Killers,” a famous Ernest Hemingway crime short story, Hopper wrote in to the publication to commend the author. “It is refreshing to come upon such an honest piece of work,” he wrote, given that, in his view, fiction was a “vast sea of sugar-coated mush” at the time. That letter shows just how enthusiastic Hopper was about pulp fiction of his day—and it was an interest mirrored in his love of film. (And in fact, when he got tired of painting, he would go to the movies, to clear his head.) The moody style of the films and books that interested him may have made its way into his art, and now it’s all come full circle, with the director Wim Wenders having alluded to Hopper’s paintings in his movies.

ENNIO LEANZA/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

His most famous painting, Nighthawks, had humble beginnings.

Hopper’s iconic 1942 painting has become ubiquitous in pop culture—TV series like CSI: Crime Scene Investigation and The Simpsons have paid homage to it through restagings, and the musician Tom Waits once used it as inspiration for an album cover. But before it was an iconic artwork, it was just a painting hanging in Hopper’s gallery. Drawing on a real-life restaurant in New York’s West Village neighborhood, Hopper painted a scene featuring three people at a diner—two of them having coffee, one of them sitting alone—while a vacant city continues on undisturbed. At the behest of Museum of Modern Art director Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Daniel Catton Rich, the Art Institute of Chicago’s director, went to see it and purchased it for $3,000—the equivalent today of a little more than $49,000.

His subjects may have been stand-ins for himself.

Scholars disagree on just how antisocial Hopper really was, but there is consensus that the chilly demeanor he gave to the men and women in his paintings may have had something to do with his own mental state. Hopper’s colleague, the painter Guy Pène du Bois, was among the first to suggest this—he claimed that Hopper had no sympathy for people at all. Whether Hopper cared about the humans populating his paintings is still not entirely clear, but one thing is for sure—they cannot be described as affected.

[ad_2]

Source link