[ad_1]

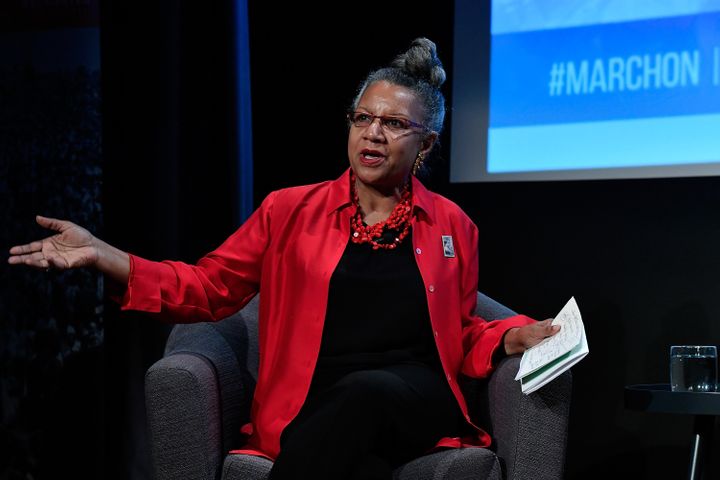

The new Netflix miniseries, “Self Made: Inspired by the Life of Madam C.J. Walker,” has sparked a renewed interest in the life of the famed entrepreneur, and A’Lelia Bundles is grateful for it.

“Millions of people now know who Madam Walker is,” Bundles, who wrote the biography that inspired the four-part miniseries about the cosmetics and hair care mogul, told HuffPost. “Now it gives me an opportunity to tell Madam Walker’s story and to tell the facts of the story.”

The facts of Walker’s life have been murky for some time, but Bundles dedicated 20 years of research to clear up some of the confusion that surrounds the millionaire’s life. That’s why, though she believed Octavia Spencer’s portrayal of Walker was amazing, there’s no substitute for the actual history.

“I really do hope people will read the book because there’s no way to put all of this life into four 45-minute episodes,” Bundles explained. “There’s a lot that I did to try to create context and historical context. And what happens in Hollywood is very different from what happens for me as a journalist. And for me, as a biographer, I’m really sticking to the facts. Everything that I put in my books can be documented.”

Netflix consulted Bundles for the miniseries, but ultimately the show was a dramatization based on Walker’s life, with fictional characters and scenes added. We talked with Bundles on Instagram Live about the miniseries and her book.

What are some of the other things people should know about Madam C.J. Walker and her daughter that were omitted from the miniseries?

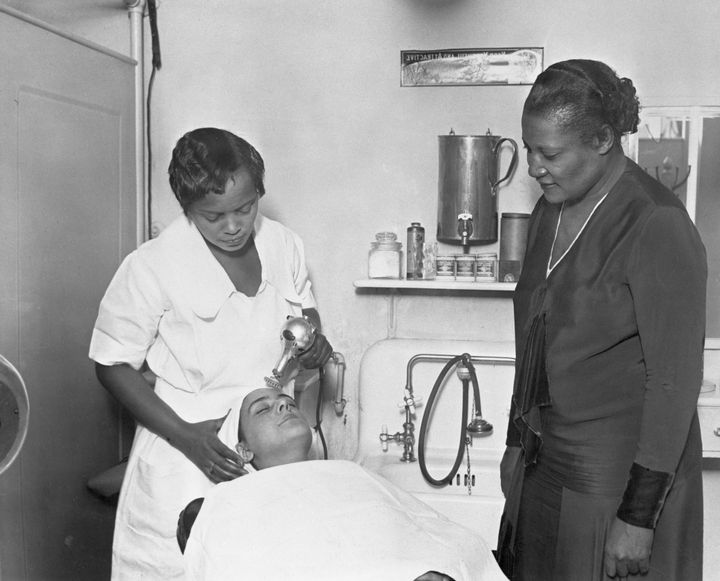

For me, what’s really important about her life was that she was nurtured, mentored, and empowered by other women. And part of that is how she got to the point of doing that for other women. When she was the poor Sarah Breedlove-McWilliams, widowed at 20, who moved from Louisiana to Mississippi, along the Mississippi River to St Louis. She had three older brothers who were barbers who were there. She began to learn the hair care business from her brothers. Their barbershop was very near Saint Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church, and it was the women of the church, like Jesse Batts Robinson, a schoolteacher, who really began to give [Walker] a vision of herself as something other than an illiterate washerwoman.

These women were part of national organizations. So that’s where she really got this idea of organizing women. So through that and carrying through the story, she starts a company. Yes, she works for [businesswoman] Annie Malone for a while, but for a short while, and then she begins to develop her own business, establishes a company, and trains thousands of women. She becomes a patron of the arts, a political activist who supports the anti-lynching movement and involved in so many other things. So that part, the philanthropy and her political activism really gets telescoped in the series.

You published a new edition of your Madam Walker biography. It was originally titled “On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker,” but it’s been temporarily renamed “Self Made” for the miniseries tie-in. What should people expect to read in this new edition?

This book was first published in 2001. A lot of things have happened; I’ve been involved in a lot of Madam Walker initiatives since then. The Madam Walker legacy center in Indianapolis, a national historic landmark, has just undergone a $15 million renovation. We were able to donate thousands of papers of Madam Walker’s letters and photographs and business records to the Indiana Historical Society. Those have now been digitized and there’s a new exhibit, but I just try to bring people up to date on all of the things that have happened since the book. I’ve also made some corrections in the book.

Anybody who is a journalist or a writer who reports the facts, every now and then, you have something that you didn’t get quite right. So I’ve done things like change “slaves” to “enslaved” because that is used more now by scholars.

One other thing that I have updated: When I wrote the book originally, because we have, as we say, the receipts, we can really document everything financially about Madam Walker, I estimated her personal estate to be between $600,000 and $700,000 at the time of her death. Her cars, her jewelry, etc. But I was speaking at a business school and one of the professors said to me, you know, when you were doing this estimate, you left out the value of her company. And when you look at the sales for the last two years of her life and the year after, one of those years was almost $600,000, which would be double that. So that person said to me if she had sold her business on the day she died, it would have been worth between $1 and $2 million.

So I have updated that with those numbers. And there are lots of people who want to argue about who was the first [Black millionaire], who wasn’t the first. That’s not really that important to me. What’s important to me is the legacy that Madam Walker left, the generational wealth she created, the women she empowered and the causes she was involved in.

In the miniseries, we are introduced to Addie Munroe [Carmen Ejogo], Madam Walker’s primary antagonist. The character appears to have been inspired by Annie Malone, a rival and another self-made Black woman millionaire. She is a legendary figure in the Midwest, which is why a lot of people took how she was depicted in the miniseries personally. What exactly was her real-life relationship with Madam Walker?

I did a lot of original research about Annie Malone. I think the writers of this series, the head writer and the showrunners, will say when they are asked about this is that they don’t intend for Addie Monroe to be Annie Malone and that she is a composite character. I think that many people have drawn that conclusion because in real life, Madam Walker’s primary competitor was Annie Malone.

In my research, I documented that Madam Walker was a Malone agent. I always say whenever I talk about her and when I write in the book that she is an important historical figure, important entrepreneur, philanthropist and person who trained thousands of Black women. So I see them as equals and that’s the way I’ve always talked about them.

So what does A’Lelia Bundles say about Annie Malone? She and Madam Walker are equals and they are rivals. There is a Malone biographer who started calling her Madam Walker’s mentor. My research suggests that it was a much more transactional relationship and not a mentoring relationship. Madam Walker’s mentors were Jesse Batts Robinson, a schoolteacher who later ran her St. Louis beauty school. Another mentor was Alice Kelly, a former dean of girls at a Black boarding school in Kentucky, who became the manager of her factory. So those were her mentors.

Can we talk a little about how Madam Walker inspired other Black women around her? I do think the miniseries did a great job in showcasing how other Black women rallied around her, like in the market scene for example.

That was one of my favorite scenes. I love that because anytime you’re trying to sell something to somebody that they aren’t already familiar with, you know, people will be like, I’m not talking to you! But you could just see how she was drawing them in. And I think that was very much a part of who she was because she had been those women. She had been that woman who didn’t have enough money, who couldn’t get a job, who was put down by other people. So she knew that story and that was part of her strength. She and Charles Joseph Walker, they moved from St. Louis to Denver. She actually moved first and started selling Malone’s products. And then he joined her. He was very helpful to her initially, but she kind of outstripped him in ambition.

As they traveled around the United States, she would go to a town, do a lecture, then she would assemble a group of maybe 10 to 15 women downstairs in the basement at the church and recruit them as agents. She had such a good eye for picking leaders: She would see who asked the best questions, who other women gravitated towards, which women had charisma. She would make those women her lead agents.

The National Association of Colored Women, the way those women are portrayed in the film is a bit different from reality. That group was founded in 1896, before the NAACP. These were women who had traveled internationally. They weren’t women who were happy to be in the kitchen. They would have said no to the kitchen. But [Walker] observed those women when she was still a poor washerwoman. They had their 1904 convention in her church in St. Louis. And she knew the power they had. So when she had her first convention of her sales agents in 1917, she was modeling it on the National Association of Colored Women. She gave prizes, not just to the women who sold the most products, but to the women who had contributed the most to charity. They sent a telegram to the president urging to support legislation to make lynching a federal crime. So this was about power. This is somewhat about hair products, but ultimately about political power.

One thing the miniseries didn’t touch on, was her political activism and philanthropy back then. Can we just talk a little about some of the things she did?

Initially, the miniseries was supposed to be ten episodes. I think that, with ten episodes, they probably could have done more with that. So I think they wanted to do more. But Madam Walker’s involvement with lynching really goes back to her childhood, when she was growing up in Delta, Louisiana. Her family minister was elected to the state Senate in Louisiana. And then he and her brothers were chased out of Louisiana by the Ku Klux Klan around the time of the 1876 election. So she had seen that there was some seeds planted, but you couldn’t get that sense of it into the film.

And the Sweetness [Bill Bellamy] character is an invented character. But that was, I think, the way that the writers were trying to make sure they introduced Madam Walker’s interest in lynching. But in fact, she was very much involved speaking out and as people who’ve read my book know, this is not in the film, that she and Ida B. Wells were spied upon by a Black spy from the war department during World War I and called “Negro Subversives,” mainly because they were speaking out. They were speaking out for Black people.

Let’s talk about A’Lelia Walker, Madam Walker’s daughter. You’re writing a book about her, right?

Yes. So I’m almost finished with the first major biography of A’Lelia Walker called “The Joy Goddess of Harlem: A’Lelia Walker and The Harlem Renaissance.” I’ve done additional decades’ worth of research. In the biography of Madam Walker, I develop the relationship between the two women. And what I found when I was writing that book is that most of the things that people knew about Madam Walker were incorrect. And I’m finding as I’m writing, most of the things people know about A’Lelia Walker are incorrect. She’s portrayed as a party girl. She’s very different from the character who appears in the series. If people go to my website, I have an article on the blog titled “The Real A’Lelia Walker Is Much More Interesting Than the Myth.”

And I have just discovered she knew everybody, all the artists and musicians and writers. She hosted the first art show for Augusta Savage, who was a very famous Black woman sculptor. She helped to underwrite some things; she hired a lot of black musicians. She also was really kind of an impresario and she knew how to have big events that would get attention. She traveled internationally to London, Paris, Rome for the coronation of the Pope, Addis Ababa, where she met the Empress of Ethiopia. So she’s a much more substantial character. So it’s really kind of painful to me to see people sort of over and over again, basically say, Madam Walker made the money, and A’Lelia spent the money. So I’m hoping that this new book will her due, which she deserves. The book will be out next year.

A’Lelia Walker was depicted as a free-spirited queer woman in the miniseries. Though there’s no concrete evidence she was, according to Tiffany Haddish, who played her in “Self Made,” the show’s writers wanted to lean into the “rumor” that Lelia was bisexual. Can you tell us a little about that?

Right. And that’s because that’s the story that I tell. So, you know, Esther [A’Lelia Walker’s love interest] is not a real character. I do not think that she would have been as out, certainly at that time before 1920 in the early ’80s when I was interviewing a lot of A’Lelia Walker’s friends who were still alive and many of whom were queer. They talked about the difference between the way people operated then and now. So people were very much more circumspect. So it would not have been out and there was nothing that I have ever found in 50, literally 50 years, of research that suggested to me that she had a relationship with a woman during her mother’s lifetime. So there would have been no conflict between her and her mother in real life. And so, I don’t know, the writers really are the ones who would have to talk about what their motivation and objective was with that character.

The real conflict between mother and daughter during her lifetime was between two boyfriends. Both doctors, both handsome. Madam Walker preferred one over the other. I write a great deal. I developed those relationships. Now a lot of A’Lelia Walker’s friends were queer. A lot of people who were at her parties, people who were queer and who weren’t queer and were very much a part of her circle of friends. She had a wide circle of friends. What I have discovered, and this is truly circumstantial and I have no letters, but my sense is that there is a relationship with a person who was a longtime friend, but I have no concrete evidence. But I, as you do when you are writing nonfiction, I will try to artfully discuss this relationship. So enjoy “Goddess.” I will be talking about it for people who are curious and for whom that matters.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link