[ad_1]

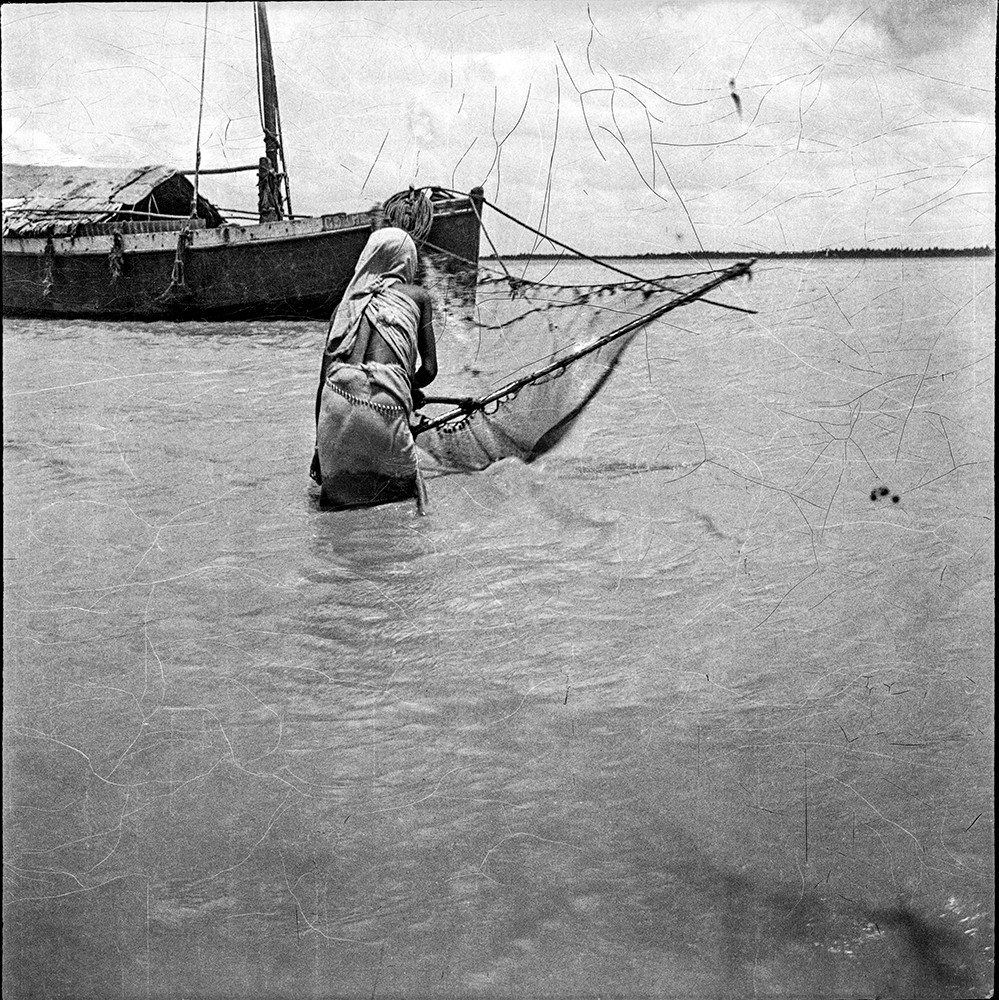

One of the most arresting images in Drik’s exhibition of works from the archive of legendary Bangladeshi photographer Golam Kasem, known as Daddy, was a black-and-white shot from 1922 in which a woman is seen from behind, thigh-deep in water and wrangling a fishing net as a boat bobs in the background. Printed from a fractured glass negative and spiderwebbed with cracks, the image suggests desiccated earth or dehydrated winter skin, an effect at odds with the subject matter.

Kasem, who died in 1998 at age 104, is considered the father of Bangladeshi photography. Born in 1894, in what was then the British Raj, he took up photography as a teenager, buying his first box camera in 1912. Though Kasem was a lifelong amateur—the exhibition text notes that he was in his nineties when he sold his first photograph—he was instrumental in the formation of Bangladesh’s photography scene. In a typewritten statement from 1990, placed in a vitrine of archival ephemera at the center of the exhibition, Kasem recounts being rebuffed repeatedly by the professional photographers from whom he sought advice early in his career. Determined to share his hard-won skills, Kasem devoted his life, as he wrote, to “imparting knowledge of photography to others.” He set up the country’s first photography organization, the Camera Recreation Club, in 1962. His scholarly achievements (such as publishing the first anthology of Bangladeshi photography in 1964), decades of mentorship, and collective approach to photography that emphasized both education and access earned him the nickname “Daddy,” which is now treated as a de facto surname.

The show focused on Kasem’s work of the early and mid-twentieth century, with many photographs dating from the 1920s. A number of them were softly lit formal portraits, the subjects posed barefoot outside against a plaid or slightly sheer black cloth. The results couldn’t be further from the Western anthropological-colonial portraits of the era. Those images show subjects with stiff carriages and guarded eyes, while in Kasem’s portraits, the postures are looser, even slouchy, in a way that suggests he had an easy rapport with the people he photographed. My Colleague (1935), a portrait of a man on the verge of a smile, is a study in jovial bonhomie, while A Close-Up Portrait (1922) beautifully portrays a man whose irises are clouded over by cataracts, seemingly captured mid-reverie.

Most magical, however, were the snapshots, particularly those of children, whom he photographed with a remarkable emotional depth. In Her First Dance (1926), for instance, a little girl wobbles into the limelight with all the awkward grace of a newborn foal, as her admiring family looks on. Friends (1948), in which a toddler bellies up to a small dog standing on its hind legs, was delightfully paired with Woman with Her Dog (1928), an image of a grinning sari-clad woman play-fighting with a large dog, similarly balanced on its hind legs, on a lawn lined with banana trees.

There is no overt political commentary in Kasem’s photographs, but given the recent violently repressive climate in Bangladesh—the gallery’s founder, Shahidul Alam, was jailed for several months in August 2018 for expressing support for protesters online—it’s hard not to read it here anyway. Three photographs of religious buildings—a temple (1929), a mosque (1959), and a church (1924), respectively, each doubled by its reflection in a body of water—were hung side by side on one wall. Clustered together, they seem to mourn the pluralism, dealt a blow by Partition, that is under attack again today, as the current regime slides toward dictatorship.

[ad_2]

Source link