[ad_1]

As the coronavirus pandemic shatters the economy and redraws society, policymakers are scrambling to find ways to soften the economic gut punch. This means policies once considered fringe are suddenly racing up the mainstream political agenda. Universal basic income ― the idea of giving people no-strings-attached cash handouts ― is one of those finding increasing traction.

The Trump administration has taken a very limited step in that direction by showing support for the $2 trillion emergency relief bill making its way through Congress. The bill includes direct payments to Americans to help them weather the economic storm.

Under the stimulus plan, individuals would receive one-off payments of $1,200 ($2,400 for couples) and an extra $500 for each child 16 or younger. The payments would be phased down for those earning between $75,000 and $99,000, and those making more would be ineligible for payments. It’s estimated about 90% of Americans would qualify for this relief.

What’s being offered is not a universal basic income. It’s means-tested, therefore not universal, and it’s just a one-time payment, not something that could help people meet their needs on an ongoing basis.

But it further opens up the long-running conversation about whether people should be entitled to some kind of guaranteed income to meet their needs. That’s something that Michael Tubbs, the 29-year-old mayor of Stockton, California, welcomes with open arms.

Tubbs has skin in the UBI game. He’s been conducting a trial of a guaranteed income in his city since February, giving 125 residents ― all of whom live at or below the city’s median income level of about $46,000 ― $500 a month in cash with no strings attached. Funded by a grant from the Economic Security Project, the project is set to last 18 months. Promising initial results show that people are using the money to help reduce income volatility.

Offering direct payments is “a great start,” said Tubbs. “I’m happy that our federal government has shown a willingness to understand… that during times of crisis, the best thing you can do is to give folks cash to navigate through.” He cautioned, though, that the amount proposed by the administration is too small to soften the enormous economic blow many people are facing, and it needs to be recurring. “It has to last at least as long as the crisis.”

This argument is echoed by two of the research leads on the Stockton guaranteed income project: Stacia Martin-West, assistant professor at the University of Tennessee College of Social Work, and Amy Castro Baker, assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania.

“While any stimulus that provides a direct cash benefit to Americans is promising, providing $1,200 per individual and more robust unemployment insurance benefits does not meet the scale of economic devastation caused by the pandemic,” wrote Martin-West and Castro Baker in an email to HuffPost.

As people scramble to cover their rent and mortgage payments due in April, they argued, offering direct payments that are likely complex to calculate, rather than a recurring and prompt cash benefit, “introduces additional bureaucratic hurdles that will delay payments and ultimately cause undue stress and financial hardship for families.”

Even before this catastrophic disruption … our economy was not working for the vast majority of people.

Stockton, California, Mayor Michael Tubbs

The concept of universal income has been around for a very long time but has been bubbling up more in political debate over the last few years thanks to the proliferation of pilot schemes around the world ― from Finland to Kenya to Alaska. The idea also gained national prominence last year thanks to former Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang, whose campaign hinged on the idea of giving every American adult $1,000 a month.

Despite this, plenty of vocal critics dismiss UBI as pie-in-the-sky thinking and, for many on the right, as a policy that would disincentivize people from working. But these concerns feel less pressing when confronted with a tanking economy.

Tubbs is grateful that a space has opened up to think more seriously about UBI. “I’m sad that it’s taken a once-in-a-century type of event, like the coronavirus, to get lawmakers to seriously consider the idea of a basic income,” Tubbs said. “But I’m thankful we’re having a conversation now because we live in a time with natural disasters, public health pandemics, etc., which seemed to be recurring, which means that folks need, during times of calm, to have the income floor to build a foundation, so when these inevitable disruptions happen, folks will have a stronger footing.”

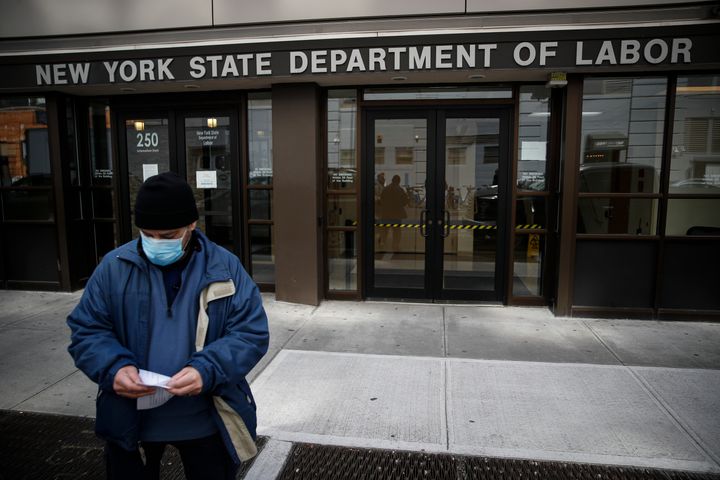

Though the scale of economic devastation wrought by the coronavirus is enormous ― nearly 3.3 million Americans filed for unemployment this week ― the American economy was in trouble long before the pandemic.

As the cost of living has risen, so too has the number of people working in precarious jobs that lack union protections and benefits such as health care, leaving people increasingly vulnerable to even small economic shocks. Research suggests that nearly half of Americans would struggle to cover a one-off emergency expense of $400.

“Even before this catastrophic disruption, a lot of folks were living in economic crisis,” said Tubbs, “and our economy was not working for the vast majority of people. It behooves all of us to ensure that everyone at least has an income floor.”

Initial data from Stockton has shown the power of providing that income floor ― even if the $500 a month is not enough to cover all of people’s basics. Results released last October found that the money was being used for essentials. The payments were loaded onto debit cards, allowing researchers to track most of them, and they found 40% was being spent on food and 12% on utility bills, with other money going to insurance payments and medical bills.

For Tubbs and the researchers, the results help bust the pervasive myth that poverty is some kind of moral failing.

“There’s a broader idea that people are financially struggling because they make bad financial choices,” Martin-West told HuffPost in October. “But I think if we look at these data… we see a sample of folks that are financially struggling but are prioritizing and making really rational decisions about how to put this money to work.”

Tubbs referred to the huge tax cuts President Donald Trump pushed for corporations in 2017. “There has been no accountability and no scrutiny about how that money was used,” he said. Instead, it was assumed businesses would put the money to good use and any failure to do so was attributed to market fluctuations.

“I think we should extend the same grace and trust to the everyday people who make our economy and who are the consumers who power these industries,” Tubbs added, “and understand that folks aren’t poor because they lack character or lack competence, they’re poor because they lack cash.”

A guaranteed income would not just have economic benefits but also health benefits, said Martin-West and Castro Baker. Not only does having a secure income enable people to buy fresher, more healthful food but research also shows that unpredictable income can cause chronic stress linked to health issues such as a higher risk of diabetes and heart disease. “How we approach the economic collapse of the pandemic has public health implications now and a decade from now,” they told HuffPost.

They called for a guaranteed income to be implemented alongside ― not as a replacement to ― existing benefits like food stamps, Medicaid and housing vouchers.

The pandemic has revealed the fragility of the typical American household’s finances, said Martin-West and Castro Baker, and laid bare the instability of our economy. “When the failures of the market mean families cannot survive a single month without a paycheck, despite having previously worked full time before the pandemic, that is evidence of a broken economic system. This requires us to reconstruct the social contract, and a guaranteed income will be part of that.”

In Stockton, Tubbs has advice for the Trump administration. “We are in an unprecedented New Deal type of situation. Go big, trust people, and the best way to bet on industry is to bet on the people who make them.”

For more content and to be part of the “This New World” community, follow our Facebook page.

HuffPost’s “This New World” series is funded by Partners for a New Economy and the Kendeda Fund. All content is editorially independent, with no influence or input from the foundations. If you have an idea or tip for the editorial series, send an email to [email protected].

A HuffPost Guide To Coronavirus

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link