[ad_1]

The Mexican Revolution, a bitterly fought struggle that ended in 1920, left a multiethnic society fractured. As part of its ambitious agenda, the reformist government that consolidated power in the 1920s used public art to unify the country. President Álvaro Obregón’s administration commissioned murals depicting Indigenous Mexicans, farmers, and revolutionary Zapatistas for the sides of the most prominent civic buildings. Leading muralists Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros, known as “Los Tres Grandes,” combined Renaissance fresco techniques with modernist forms and leftist iconography. They formed a template for postrevolutionary art that included Rivera’s classical style of composition, which borrowed from both cinematic montage and pre-Columbian sculpture; Orozco’s expressionistic mythography; and the dynamic approach to representing three-dimensional space that Siqueiros called “polyangular perspective.”

This politically radical avant-garde inspired a generation of young painters based in the United States who made pilgrimages to Mexico, worked as assistants to Mexican artists, and created murals in both countries. The standard narrative of American painting has long focused on the notion of European-influenced modernism erupting into postwar Abstract Expressionism. But this potted history obscures the work of diverse artists who pursued figurative modes between the 1920s and ’40s and looked to Mexico City as much as to Paris for models to emulate. This Pan-American inheritance is restored in the Whitney Museum’s monumental exhibition “Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925–1945.” Featuring a formidable number of paintings, studies, and large-scale reproductions of key works by the Mexican muralists alongside contemporaneous pieces by US-based artists, from Jackson Pollock to Charles White, the show affirms the political potential of visual art. At a moment of tension between the US and Mexican governments, it details rich cross-border cultural exchanges, offering a timely reminder that “American art” encompasses the art of all the Americas.

“Vida Americana” conveys the global fascination with postrevolutionary Mexico. Leon Trotsky received temporary refuge in the country, and Sergei Eisenstein, whose unfinished film ¡Que viva México! (begun 1930) is on view at the Whitney, found inspiration there. Photographers from the US, like Edward Weston and Tina Modotti, documented Mexico’s geometric pre-Columbian monuments and newly empowered campesinos. The curatorial team, led by Barbara Haskell, rightfully frames the muralists’ appeal as an explicitly modernist one. As the painter Reuben Kadish is quoted in the catalogue as saying decades later, “Siqueiros coming to LA meant as much then as did the Surrealists coming to New York in the forties.” If the later influx of Europeans like André Breton and Salvador Dalí incited a dive into the subconscious, the Tres Grandes artists, each of whom traveled to the US to complete major projects between 1927 and 1940, prompted a fervent desire to create public-facing works.

Siqueiros established a “Bloc of Mural Painters” in LA, and two of its members, Kadish and a young Philip Guston, traveled to Mexico to paint The Struggle Against Terrorism (1934–35) at the University of Michoacán. This dynamic allegory of inquisitorial violence, represented in the exhibition as part of an architectural model, shows an onslaught from menacing, hooded figures—images that would reappear in Guston’s later work. Other US artists joined the Mexican Syndicate for Technical Workers, Painters, and Sculptors, like Pablo O’Higgins, who invited a group of volunteers to Mexico City in 1935 to complete a series of murals at the Abelardo L. Rodríguez Market, under Rivera’s supervision. Among them was Isamu Noguchi, who produced History as Seen from Mexico in 1936, one of the rare sculptural reliefs from the period.

In the US, Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros found common cause with regionalist artists who aimed to show the lives of working Americans throughout the country. On loan are five canvases from Thomas Hart Benton’s revisionist American Historical Epic (1924–27), depicting European settlement of the US as a story of violence and dispossession. In 1930–31, the New School in New York commissioned both Benton and Orozco to paint murals for its expansion. Benton’s America Today (1930–31), a panoramic sequence illustrating progress in industry and agriculture, complemented Orozco’s Call for Revolution and Universal Brotherhood (1930–31), a five-panel fresco incorporating likenesses of Gandhi and Lenin into a globe-spanning narrative of decolonization and working-class revolution. Galvanized by the muralists’ emphasis on racial solidarity during the Jim Crow era, African American artists including White and Jacob Lawrence adopted their Mexican counterparts’ narrative techniques, bold colors, and gestural clarity to foreground the experiences of black people in the US.

Progressive American artists found support in the New Deal–era Federal Art Project, which commissioned hundreds of artists to adorn public buildings throughout the US during the Depression. The Whitney exhibition features several fascinating studies from this period. Ben Shahn, an immigrant from Lithuania who had worked as Rivera’s assistant, produced a three-panel mural for the Jersey Homesteads housing project depicting the immigrant experience through representations of his mother alongside Sacco and Vanzetti, Einstein, and garment workers on New York’s Lower East Side.

The picket lines, protests, and scenes of racial injustice prominent in FAP works formed a repertory that would be evoked in postwar folk and protest songs. The muralists’ most lasting influence, however, might have been in the development of Abstract Expressionism. Jackson Pollock is the key figure here, and the Whitney includes several telling examples of his evolution. A student of both Benton and Siqueiros, Pollock was likely encouraged to develop his signature drip technique by observing Siqueiros’s wide-ranging experiments with blowtorches, airbrushes, and other industrial tools. Pollock’s Untitled (Naked Man with Knife), 1938–40, one of a dozen works by the artist on view, strains toward abstraction, its swirling mass of color foreshadowing his later breakthroughs.

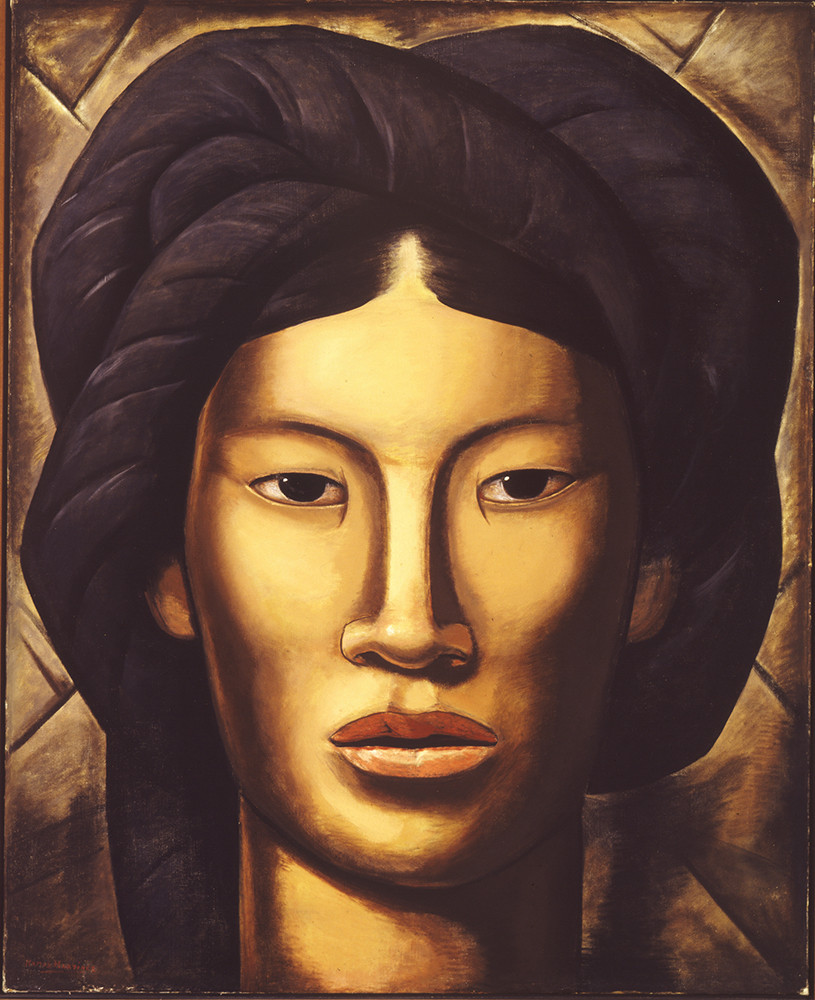

Museum of Modern Art, New York/© 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SOMAAP, Mexico City.

Despite the exhibition’s strengths, “Vida Americana” never quite explains why so many of the artists from this period would later turn inward, transmuting political passion into private expression. Leftist disillusionment with the USSR peaked during the Moscow show trials, and, for many, the previously popular art of social realism took on a propagandistic pall by the 1940s. The nature of arts patronage in the United States also played a role. Rivera, who in Mexico relished in portraying grotesque oligarchs, became dependent on the very patrons he had caricatured, his work shading into a sort of techno-utopianism in murals for the auto industry–backed Detroit Institute of Arts and the Rockefeller Center. Bothered by allegations that he had grown too cozy with industrialists, Rivera included a figure of Lenin in the latter mural, a dazzling allegory of social and scientific progress. Man at the Crossroads (1933) was promptly painted over, and Rivera returned to Mexico to re-create a smaller-scale (but still massive) version at the Palacio de Bellas Artes, a reproduction of which is on view in the last gallery of the show.

The curators have approached the unique challenge of muralism’s site-specificity in a variety of ways, including by exhibiting several such reproductions. Replicating the original position of Orozco’s Prometheus (1930) in the dining hall of Pomona College in Claremont, California, the titular figure appears to strain against an arched niche approximated in the Whitney gallery at smaller scale. Still, “Vida Americana” might ultimately leave viewers with a sense of how uneasily these works sit in a museum. Some look as stunned by their descent as the first religious frescoes transported from the church to the gallery did. Their presence as aesthetic objects to be admired in a museum acknowledges a desacralization—or at least a kind of depoliticization.

“Vida Americana” is a laudable effort to preserve a history of public art that has sadly proved less than permanent, but one hopes that it will inspire pilgrimages to the sources: the Abelardo L. Rodríguez Market, for example, whose extant murals can be contemplated amid the sounds of vendors hawking produce. That would be the greatest testament to the fact that a popular art that doesn’t condescend to its viewers, and an experimental art that doesn’t abandon them, can still be worthy of devotion.

This article appears under the title “’Vida Americana’” in the April 2020 issue, pp. 75–77.

[ad_2]

Source link