[ad_1]

In front of a crowd of 20,000 people mourning Kobe Bryant, WNBA player Diana Taurasi recalled watching the NBA legend play at The Forum and how he “made this little girl believe she could be a Laker one day.” Beyoncé gave a soul-stirring performance of “XO” and “Halo;” Michael Jordan, through tears, remembered the “little brother” who texted him at 2 a.m. to ask for coaching advice. Vanessa Bryant, Kobe’s wife and mother of their four children, eulogized her husband and daughter, Gianna, in a heartwarming 20-minute speech.

These moments will forever be etched in our minds after the celebration of life for Bryant and Gianna at Los Angeles’ Staples Center on Monday. Public memorials like these — often called homegoings in the Black community — are traditionally marked by emotional remarks and heartrending songs. To honor a celebrity’s life, homegoing services are comforting to those of us who struggle to express why the death of a luminary, who is so often a virtual stranger, affects our lives so deeply.

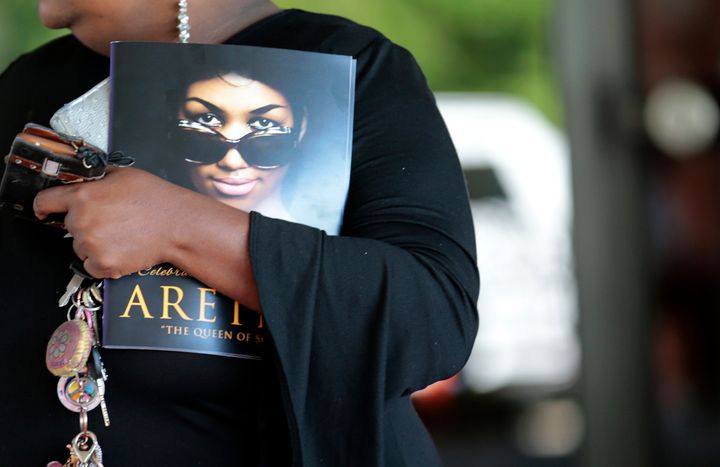

We have felt this connection time and again recently with the deaths of legendary singer Aretha Franklin, Grammy-nominated rapper Nipsey Hussle and literary giant Toni Morrison.

Bryant encouraged us to reach for our dreams. Franklin gave us poignant music that continues to touch our souls. Nipsey Hussle reminded us to keep fighting for our neighborhoods. Morrison instilled in us a reason to live. Of course, their homegoing celebrations were filled with memorable moments, too. Stevie Wonder (with Angie Stone, Jenifer Lewis, Shirley Murdock and Dottie Peoples) left the congregation breathless during a staggering rendition of Aretha Franklin’s “Until You Come Back to Me.” Kameron Carter, the 9-year-old son of Lauren London, encouraged the congregation to yell out “Respect!” for Hussle. Jesmyn Ward beautifully encapsulated what Morrison meant to so many: “She found us in the deserts of ourselves … and she saved us.”

These homegoings are among the most recent public memorials that reinforce a long legacy in the African American community. Going as far back as slavery, they were the only way for Black people to bury their loved ones. Slaves viewed death as the only true way to be free as they could not return to their native Africa; death meant their souls could go home to the Lord. Karen West Butler, who owns West Funeral Home, one of the oldest Black-owned funeral homes in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, explains that homegoings have historically allowed Black people control over their destiny in an ethereal sense.

“As the old-time ministers used to say, we’re really pilgrims just passing through,” Butler told HuffPost. “You’re going back to the one who gave you life. So, homegoing services help give them more comfort.”

That’s why homegoings, amid immeasurable despair, have always provoked a sense of hope and power. Back in the day, the services consisted of gospel hymns, like “Sweet Sweet Spirit” and “When We All Get to Heaven,” and prayers among an intimate group of loved ones. But in today’s celebrity-driven social media era, homegoings have often become live-streamed ceremonies watched and commentated on by fans across the globe in collective mourning over a beloved star.

In 2009, just three years after the launch of Twitter, viewers everywhere could barely keep their own tears back as they watched an emotional 11-year-old Paris Jackson step up to the microphone and say a few words about her father, Michael, at his homegoing at Staples Center. At Whitney Houston’s broadcasted memorial in 2012, Rev. Marvin Winans and his family singing “Tomorrow” at the New Hope Baptist Church in New Jersey stirred an audience of 1.7 million.

Due to the rising popularity of public homegoings for celebrities, funeral directors have had to supply extra staff members, security, sprinters, food and accommodations for the increased number of speakers (which often includes fellow luminaries). That’s on top of the cost of the casket, which could range from $900 to $60,000, according to Carol Williams, executive director of the National Funeral Directors and Morticians Association Inc.

“It can really be an all-day affair,” Williams said. Her funeral home, Carl M. Williams Funeral Directors in Atlanta, presided over civil rights leader Juanita Abernathy’s homegoing last year.

But now that homegoings have gone mainstream, they’ve added a complexity to what was once an exclusively Black, very personal form of grieving in the Black community. Homegoings today dominate the list of trending topics on Twitter and have opened up a space for everyone — not just Black people — to not only share an opinion on each moment of the program but also to condense Black grief to 240 characters (or in best scenarios, a thread). Even journalists like Slate’s Rachelle Hampton, who covered Morrison’s homegoing, are conflicted about the way that affects how Black grief is seen and discussed.

“I think it makes our grief more publicly accessible in a way that I don’t think is necessarily great,” Hampton said. “It’s turned things that have been kind of insular into public spectacles in a way that I am still struggling with figuring out if that’s a good or bad thing.” She likens how people live-tweeted Franklin’s homegoing to the way fans live-tweeted about “Scandal,” though “obviously in a much more respectful fashion.”

Part of that conflict comes down to the fact that Black fans feel a claim over Black celebrities who represent a type of success that has a particular significance for the community. There’s a need to isolate that celebrity even in death so that the context of their legacy can remain preserved.

“When someone in our community makes it to a certain level, we still feel like we have a certain level of ownership,” Hampton said, adding that that communal desire to protect one of our own has helped draw us closer together in the digital age. “I think the power of collective grief allows us to not feel alone because of how connected we are on the internet.”

Though the increased spotlight on Black homegoings has helped us process Black grief in a more communal sense, fewer non-celebrity homegoings have been able to reap the same benefit. More Black people are opting for cremation rather than a homegoing service, primarily to cut costs. That not only poses a concern for Black-owned funeral directors, but it also interrupts what has become a necessary source to communicate our grief and reflect on the person who’s passed on.

“‘What about your family or the people who you encounter day to day?’” Williams asks whenever someone requests cremation. “It’s unfair to them to just do cremation and not do any type of service. That’s the way we grieve for our loved one — going to service, talking about them and singing songs about that person.”

The lifespan of non-celebrity homegoings remains to be seen. But we can at least rest assured that those of notables like Morrison, Franklin, Hussle and now Bryant have brought a new resonance to the way we’ve long honored those whose lives mattered so much to us — and whose spirits will carry on.

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link