[ad_1]

For almost her entire life, her seminal work in American space travel went unnoticed. Only recently has Johnson’s genius received national recognition.

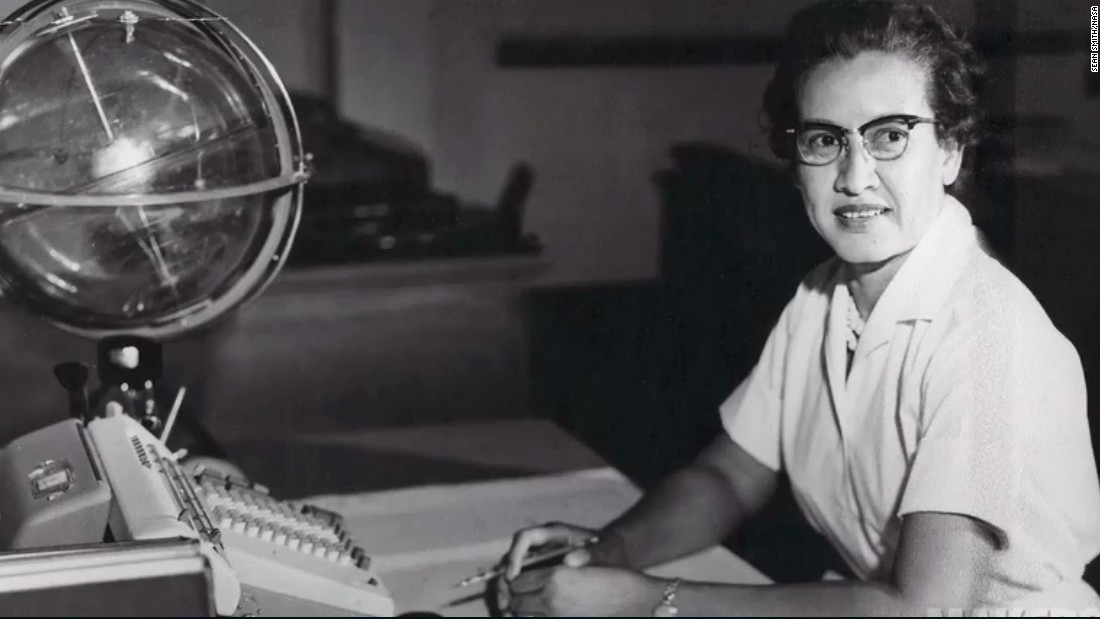

Johnson, a pioneering mathematician who, along with a group of other brilliant black women, made US space travel possible, died this week. She was 101.

Johnson was part of NASA’s “Computer Pool,” a group of mathematicians whose data powered NASA’s first successful space missions. The group’s success largely hinged on the accomplishments of its black women members.

Her work went largely unrecognized until the release of 2016’s “Hidden Figures,” a film portrayal of Johnson’s accomplishments while the space agency was still largely segregated.

Her talent was evident early on

She started her career as a teacher but had her sights set on mathematical research.

Following an executive order that prohibited racial discrimination in the defense industry, Johnson was hired at NACA, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics and NASA’s predecessor. She was one of several black researchers with college degrees hired for the agency’s aeronautical lab through the initiative.

She started in 1953 in the facility’s segregated wing for women before she was quickly transferred to the Flight Research Division, where she remained for several years.

But midway through the ’50s, the space race between the US and the Soviet Union began to intensify. So did Johnson’s career.

She was tasked with performing trajectory analysis for Alan Shepherd’s 1961 mission, the first American human spaceflight. She co-authored a paper on the safety of orbital landings in 1960 — the first time a woman in the Flight Research Division received credit for a report.

Despite often being the only woman in briefings, she quickly gained notice for her accuracy. John Glenn requested her help before his orbit around Earth in 1962. He was skeptical of the computers that calculated his spacecraft’s trajectory, so he told engineers to “get the girl” and compare Johnson’s handwritten calculations to the computer’s.

“‘If she says they’re good, then I’m ready to go,'” Johnson remembered Glenn saying.

She gave the OK, and Glenn’s flight was a success. His mission — and Johnson’s role in it — helped nudge the US ahead in the space race.

By the time Johnson retired from NASA in 1986, she’d mapped the moon’s surface ahead of the 1969 landing and helped astronauts aboard the Apollo 13 safely land back on Earth.

Her work was ignored for decades

After the release of the book “Hidden Figures,” which was published in 2016 and turned into a film the following year, officials lobbed heaps of praise on Johnson and two other black women mathematicians in the agency’s Computer Pool, Dorothy Vaughan and Mary Jackson.

In 2015, President Barack Obama honored Johnson with the Presidential Medal of Freedom for her pivotal work in American space travel.

But before all of that, Johnson’s work went largely unrecognized. Around the office in the 1960s, she and her colleagues were called as “computers in skirts” and worked in a segregated facility.

Praise for their work was certainly overdue, but Johnson resisted taking full credit for the Computer Pool’s accomplishments. “We always worked as a team,” she said in a 2010 interview. “It’s never just one person.”

Fans mourn an American hero

“Ms. Johnson helped our nation enlarge the frontiers of space even as she made huge strides that also opened doors for women and people of color in the universal human quest to explore space,” he said in a statement. “At NASA we will never forget her courage and leadership and the milestones we could not have reached without her.”

Sen. Kamala Harris, who introduced a bill to honor Johnson and the “hidden figures” in 2019, mourned the passing of the “icon and brilliant mathematician.”

CORRECTION: This story has been updated to correct the year ‘Hidden Figures’ was released.

[ad_2]

Source link