[ad_1]

The defining work of the winter season in New York is a small painting of a nude female figure crouching in a black void, her body barely visible before a mysterious emanation—a white-hot corona, perhaps, or maybe the aftershock from an explosion. The painting was left unfinished when a bomb was dropped on artist Layla Al-Attar’s house in Iraq by the American military in 1993, killing her. It now serves as a kind of de facto memorial.

Al-Attar’s Unfinished painting is one of more than 250 works in “Theater of Operations: The Gulf Wars 1991–2011” (on view through March 1), a timely exhibition at MoMA PS1 that channels anxieties past and present. Organized by PS1’s chief curator, Peter Eleey, and PS1 curator, Ruba Katrib, the exhibition surveys ways that American intervention in Iraq over two decades of war influenced art in and beyond the Middle East. And it resonated more than a little eerily when new threats of war mounted in the region this past January, this time with Iran.

Private collection

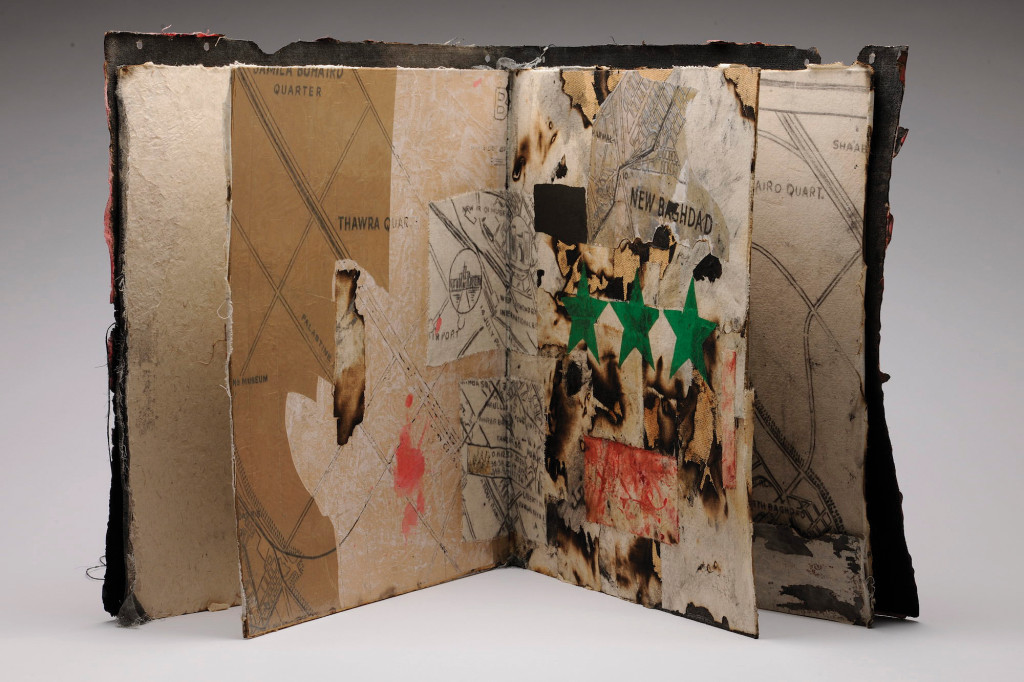

One of the show’s great discoveries is the dafatir, a type of working notebook that Iraqi artists created when they had limited access to other art materials. Examples by Mohammed Al Shammarey, Kareen Risan, Mahmoud Obaidi, and others are dense collages of ready-made text culled from newspapers, personal writing, figurative portraits, and frantic abstraction that were all the more potent for their humble format.

While Iraqis experienced the war firsthand, Westerners watched it on screens. This phenomenon provided fodder for several artists in the exhibition. Cory Arcangel crafted a shocking piece called Bomb Iraq (2005), a computer game in which players click a mouse to drop warheads, and Rainer Ganahl made a series of paintings that intricately render pages from several news websites. A number of works deal with torture. For a haunting black-and-white print, Richard Serra fixed on an uncharacteristically blunt figure evoking widely published photos of abuses at Abu Ghraib prison; Tony Cokes’s powerful text-based videos address the deafeningly loud rap, metal, pop, and rock music that tortured inmates.

Vija Celmins experienced war firsthand, though you might not know it from the coolly analytical paintings, sculptures, and works on paper at her survey exhibition at the Met Breuer (closed January 12). Celmins spent part of her childhood in oppressed countries during World War II—first, Soviet-occupied Latvia, then, Nazi-occupied Germany. With her low-key works from the ’60s, she returned again and again to her memories of conflict, often appropriating pictures of death and disaster in melancholy drawings rendered in seemingly infinite shades of gray. In one, fighter jets zoom across the sky on a TV screen that is itself set against an otherwise vacant sky; in another, a man on fire leaps from a burning car. These early pictures are muted and removed in ways that seem at odds with their subject, and they linger in the mind all the more as a result.

Such pieces set the tone for the show, encouraging a dark reading of subsequent works. In a few of Celmins’s well-known skyscapes, light from dying stars streaked across the blackness that surrounded them, suggesting that where there is beauty, there may be violence.

Princeton University Art Museum

A long-overdue show for Zilia Sánchez at El Museo del Barrio (through March 22) takes up similar themes. For more than 50 years, Sánchez, a Puerto Rico–based artist who was born in Havana, has been making assertively sensual, shaped canvases that push abstract painting into the third dimension. Many of her works, rendered in cool blues and pallid grays, feature breast-like protuberances and vagina-like creases. But these are not passive images of femininity—they’re tensed-up visions of womanhood gone to war, with wooden armatures beneath the surface that seem to threaten to poke through the canvas. Many works bear titles alluding to strong-willed females of Greek mythology, such as the women of Troy.

With the exception of one work—Represión (1998), a slab of cement with a grid of iron bars impressed atop it that the show’s curator, Vesela Sretenović, suggests may refer to the colonization of Puerto Rico—Sánchez has not made overtly political art. But much of the work she produced during the 1960s and ’70s, when second-wave feminism was taking hold around the world, evidences what may be a more radical undercurrent. Sánchez’s sole self-portrait—a 1954 image of herself as a nude Amazon warrior, her hair flying up around her, her eyes cast toward the viewer—seems to offer a clue as to her true intentions.

At the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Kent Monkman, a Canadian First Nations artist of Cree and Irish ancestry, stares down the long-standing denigration of Indigenous peoples through two enormous paintings displayed in the Great Hall entryway (through April 9). Working in the tradition of artists like Kerry James Marshall, Monkman borrows some of the forms of iconic American history paintings and subverts them, inserting Indigenous characters—including his gender-fluid alter ego Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, who here wears nothing more than a silky red fabric and black stilettos—in place of the white figures who have historically populated such images.

The litany of issues to which Monkman alludes—the legacies of slavery, the whiteness of art history, and the breakdown of gender norms, to name just a few—is heady and intense, and the pictures themselves are frenetic. Monkman excels at layering the present onto the past and vice versa. One of his paintings, Resurgence of the People (2019), plays on Emanuel Leutze’s iconic 1851 work Washington Crossing the Delaware (also on view at the Met)—but instead of depicting a channel lined with ice floes, Monkman transports the action to the middle of a choppy ocean, and in place of a snow-capped New Jersey shoreline visible in the distance, the artist offers a craggy isle peopled with white nationalists who stand by with assault rifles.

Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art

Alan Michelson, a Mohawk member of the Six Nations of the Grand River, subverted suggestions of tradition in a Whitney Museum show (closed January 12) with videos and augmented-reality works that addressed the surveillance of Indigenous peoples and the exploitation of the land they live on. The best work wasn’t on the museum’s walls, however—it played out on visitors’ phones.

In a 2019 AR piece produced with Steven Fragale titled Sapponckanikan (Tobacco Field), viewers could point their phones around the Whitney’s spacious ground floor and see digital tobacco plants sprouting everywhere—a reference to the crops that might have grown where the Whitney stands had the land not been seized from the Lenape people. Looking at the apparitions brought to mind recent protests at the Whitney, in which acknowledgments that the museum stands on Native land were a regular feature.

Also at the Whitney was one of the season’s most exciting and chaotic shows: a mid-career survey of New York–based Rachel Harrison (closed January 12), whose beguiling, elusive, and idiosyncratic assemblages of everyday objects, photographs, papier-mâché, and more have made her perhaps the finest sculptor at work today.

For her 1996 installation 1:1 (Wonton: John), Harrison scoured New York City for images of men named “John”—a John Stewart album cover, a painting of the critic John Perrault in the nude, a poster of Jon Bon Jovi, and so forth—and then placed them alongside 38 clay wontons of disparate color and size. She seemed to be punning art history by paying homage to various namesakes including Jasper Johns (one of her major inspirations—and the subject of a big Whitney show later this fall), and there may even be a feminist context around the concept of johns, as the clients of female sex workers are known.

Courtesy Greene Naftali, New York; Photo: Tim Nighswander/IMAGING4ART

Some have accused Harrison of lacking coherent ideas, a criticism unfortunately warranted by a series of drawings in the show that placed crudely sketched versions of late pop star Amy Winehouse alongside female models appropriated from Martin Kippenberger, Pablo Picasso, and other sources. Why Amy Winehouse? Why art history? It was all a bit glib in a way that seemed to turn Winehouse’s death from alcohol poisoning into a punchline.

But Harrison taps convincingly into a sense that too many ideas circulating all around us make it impossible to home in on any one of them. Art, she seems to propose, has the ability to suck it all in and spit it back out at the viewer in novel ways. It might not make sense, but it will open up new ways of understanding.

Among Harrison’s finest works here was a 2006 sculpture that features a Hallmark greeting card rack adorned with fake peaches, a rotary phone, an image from a 1982 artwork by Hans Haacke (which itself appropriates Marcel Broodthaers), and a snow shovel, all in place of ostensible goods for sale. If Harrison is peddling anything, it’s concepts, with a welcome side of bawdy humor in its title: Nice Rack.

A version of this article appears in the Spring 2020 issue of ARTnews, under the title “Uneasy Pieces.”

[ad_2]

Source link