[ad_1]

By Nick Robertson

The Associated Press/Savannah Morning News

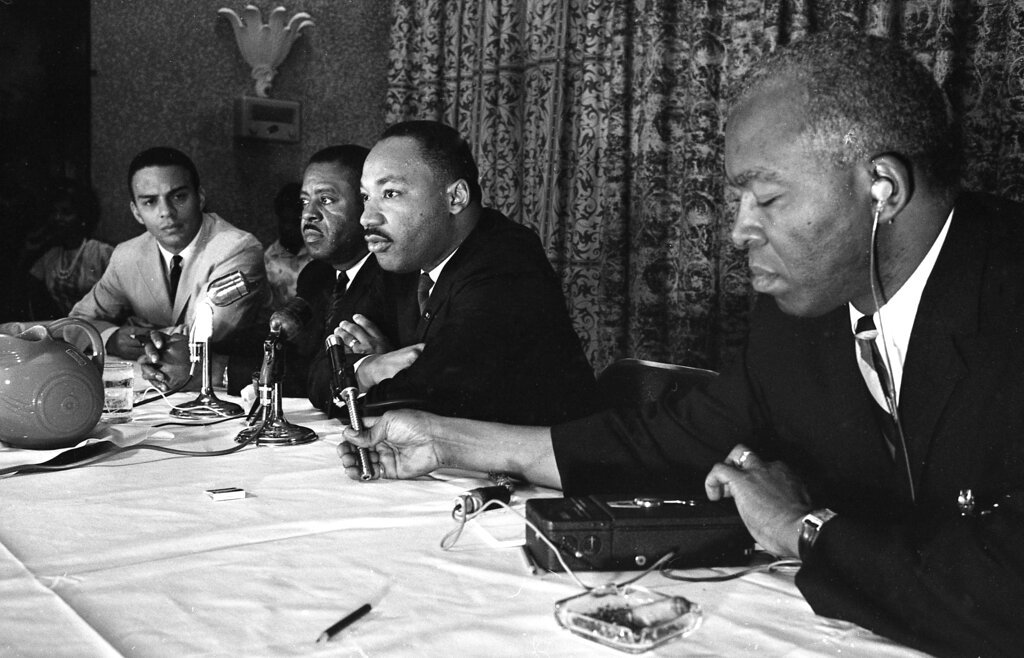

As Savannah Morning News photo chief Steve Bisson worked through a half-century-old box of negatives to catalog and scan, he made a discovery. Submerged within the newspaper’s old photo files, 14 negatives provided documentation of two Savannah appearances by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1964.

According to the newspaper’s records and a copy of the February 1964 Southern Christian Leadership Conference newsletter presented by Tougaloo College’s online Civil Rights Movement Archive, King visited Savannah at least twice in 1964. The newly discovered photos show the civil rights leader when he gave a speech early in the year at the Savannah Municipal Auditorium to promote voter registration, and then again in late September when the eighth annual SCLC convention was held in Savannah.

Former Savannah Mayor Edna Jackson, who was active in the civil rights movement with the NAACP in various communities around the South in the 1960s, remembers that when King visited Savannah, he was impressed by the local leaders who were advocating for racial equality.

“Savannah didn’t need any help, so he left, because he felt Savannah had great leadership,” Jackson said.

She said King worked with her mentor, Savannah civil rights legend W.W. Law, who had helped the community make great progress toward desegregation since the early 1950s.

“Savannah started integrating before the Civil Rights Act was passed,” Jackson said.

But as every year goes by, and an increasing number of youths anticipate Martin Luther King Jr. Day more as a holiday than a commemoration, Jackson asserts that time is of the essence when it comes to teaching the civil rights movement’s significance.

“We have not told our stories,” Jackson said. “We are losing those stories.”

Looking back at those times, Jackson vividly recalls joining local civil rights demonstrations during the early 1960s, including sit-ins at segregated Broughton Street businesses and wade-ins at Tybee Island’s Whites-only beaches. Although the authorities sometimes reacted harshly to these movements, she was not intimidated by potential brutality.

“You knew you were doing the right thing,” Jackson said, crediting Law for teaching her and many other Savannah civil rights activists to stand up for themselves with courage and peaceful resistance. “I was mesmerized by the kind of things I learned at that early age.”

Jackson is one of Savannah’s few surviving participants in the civil rights movement from the time when King led it, before his assassination April 4, 1968, in Memphis, Tenn. When archived photos were examined by Vaughnette Goode-Walker, the director of Savannah’s Ralph Mark Gilbert Civil Rights Museum, she was unable to recognize any pictured locals who are still alive.

“Unfortunately, it was like looking at ghosts,” Goode-Walker said, noting that the loss of people with firsthand experience in the civil rights movement increases the imperative nature of properly educating 21st-century African American youths about the struggles for equality that their ancestors endured.

“Our young people are so technology-driven, they don’t want to pick up a book and read it,” Goode-Walker said of civil rights history. She said the many gains achieved by civil rights trailblazers have created a situation where youths take their hard-fought rights for granted, increasing the challenge of passing on King’s legacy. “How do you relate to them?”

Jackson agrees that preserving and advancing racial equality can only be achieved by passing on detailed accounts of what King and many other civil rights activists experienced.

“I really don’t feel like we’ve told our story,” Jackson said. “These kids don’t know how the schools integrated. They don’t know why they can be managers at stores on Broughton. … They don’t know the sacrifices.”

At Savannah’s Civil Rights Museum, Goode-Walker imparts the movement’s spirit to elementary school students by leading them in simulated demonstrations, complete with handmade protest signs and loud chants.

“I do mock protests here with the kiddos,” Goode-Walker said, explaining that she lets the schoolchildren hold a demonstration for the cause of their choice. “They’ll say, ‘Longer lunch! Longer lunch!’”

No matter how irreverent the children’s chosen cause may be, Goode-Walker brings it back to the civil rights movement by explaining that such demonstrations were commonplace in Savannah at businesses that engaged in discriminatory practices.

“‘Imagine if we did that at a store,’” Goode-Walker tells the schoolchildren at the conclusion of their mock demonstrations.

Jackson believes that teachers are essential to preserving the legacy of King and the civil rights movement.

“The outreach has to be within the public school system,” Jackson said, encouraging teachers to empower their students with lessons in civil-rights history. “What are you doing to let these young people know the power that they have?”

[ad_2]

Source link