[ad_1]

Michael Zeldin served as deputy independent counsel and later independent counsel in the investigation into allegations that the administration of George H. W. Bush violated the privacy rights of candidate Bill Clinton in the 1992 presidential campaign. Robert Ray served as the independent counsel from 1999 to 2002, during which he led the investigation into the Whitewater controversy.

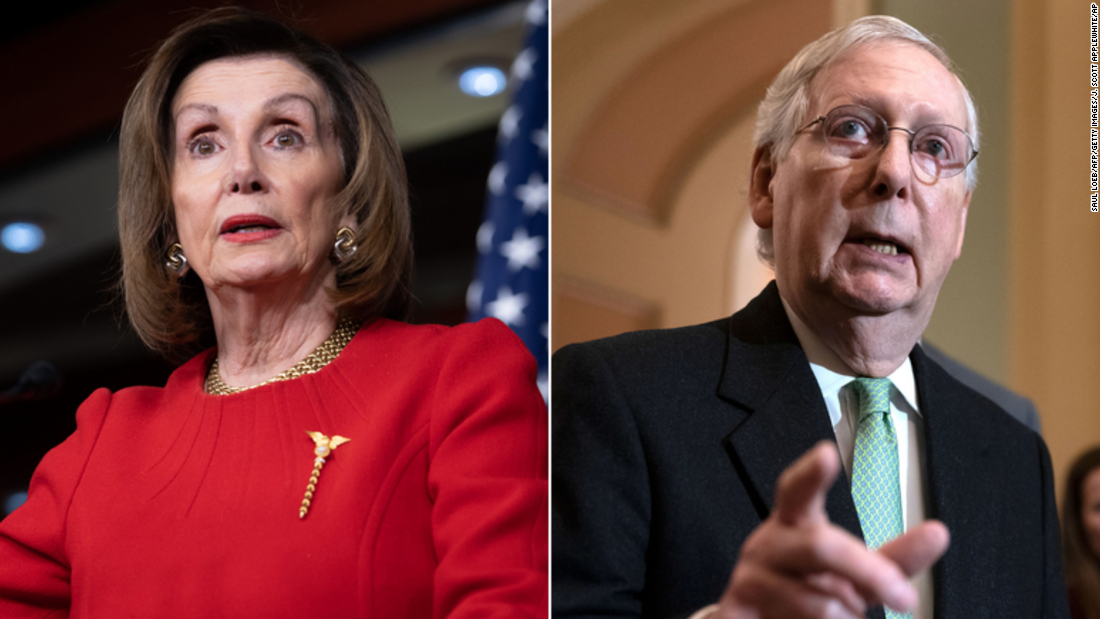

Question: Speaker Nancy Pelosi says the House will consider a resolution next week to send the two articles of impeachment against President Donald Trump to the Senate, which is preparing for a trial. Former National Security Adviser John Bolton made clear this week that he would testify if the Senate asks, and Democrats are pushing for him to be among the witnesses. But Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has said he wants to delay a decision on whether to hear from any witnesses in the trial until after the two sides present their arguments. What should the Senate do?

Michael Zeldin: The Senate should subpoena Bolton and take his testimony.

You can’t miss the irony in the differing positions of Senators Chuck Schumer and Mitch McConnell about the need to call witnesses at the Senate’s upcoming impeachment trial. That is, President Trump steadfastly has maintained that his telephone call with Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelensky was perfect, that he was acting within his constitutional powers and that he did nothing improper, let alone impeachable.

In legal terms, the President has presented an affirmative defense to the articles of impeachment which allege that he abused the powers of his office by his phone call and his subsequent acts. Yet as impeachment moves from the Democratic-controlled House to the Republican-controlled Senate (a home court advantage for the President), McConnell is not permitting testimony from John Bolton and the other witnesses who could support the President’s claims that he did nothing wrong and that he is the target of a partisan witch-hunt.

Schumer wants the President to have that opportunity. One would think that, if there were witnesses and other evidence to support the President’s claims of innocence, he would insist that McConnell allow that evidence to be presented for the American public to hear.

The fact that McConnell has not provided any assurances that he will allow witness testimony or other documentary evidence and that he has been coordinating his strategy with the White House, reasonably gives rise to the inference that there is no exculpatory evidence by firsthand witnesses that would support the President’s bald assertions of innocence. If the Senate does not call Bolton and the other witnesses with firsthand knowledge of the President’s actions, it would be facilitating a cover-up, and this is how history will record it.

Robert Ray: The answer to the question of what the Senate should do is precisely what is necessary — and no more — in order to determine whether the articles, in the first instance, are sufficient to warrant the President’s removal from office.

All of this can be determined by the Senate potentially without witnesses and certainly without any obligation on the President’s part to come forward with exculpatory evidence. Since when is that necessary? Not since the passage of the Bill of Rights. There is no obligation by a defendant in this country in any proceeding — impeachment or otherwise — to prove his innocence.

Zeldin: In my view, the witnesses who testified in the House established, as a threshold matter, that the President abused the powers of his office when he asked President Zelensky to investigate his political rival and ordered the withholding of military aid until the investigation was announced publicly. The President’s refusal to authorize any witness testimony or the production of any relevant documents constituted an obstruction of a duly authorized Congressional investigation. Applying Robert’s test of “in the first instance,” on this record alone a sufficient evidentiary basis exists to remove the President from office.

The President has denied the charges and has asserted that what he did was, not only proper, but within his constitutional rights as President. Whether that position is sustainable only can be determined through witness testimony and the production of documents.

Robert is correct that the American criminal justice system does not require anyone charged with a crime to prove his/her innocence. I am not suggesting that the President has that legal obligation. Rather, as a political matter, I would expect the President to insist that the Senate call witnesses to establish that he did nothing wrong.

Ray: I suggest in response simply that we return, then, to the wisdom of the founders, the Constitution and historical practice. Experience and history demonstrate that only when there is clear and unmistakable evidence of impeachable crimes also constituting an abuse of the public trust will there ever be the requisite bipartisan support to remove a president from office. Anything short of that is contrary to the best interests of the country and can await the next election. In short, you don’t need witnesses and further documents in order to figure that one out. I suspect that’s where, ultimately, we are headed at an impeachment trial in the Senate when, and if, the articles of impeachment are delivered by the House.

Zeldin: Robert is correct that when there is clear evidence of criminal conduct that constitutes an abuse of the public trust bipartisan support for impeachment and removal will likely follow. The Nixon impeachment process is one such example.

Regardless of the standard to be applied, unless the Senate stands up to the President and performs its constitutional duty to hold a full and fair trial in which all relevant witnesses testify under oath and all documentary evidence is disclosed, the President’s cover-up will continue and his conduct will go unchecked. This would be an inexcusable breach of the Senate’s constitutional responsibility and, in Robert’s words, “contrary to the best interests of the country.”

Ray: As to the merits of the second article of impeachment, what is most disconcerting and galling to the President and the 63 million voters who supported him in the last election is that a partisan majority in the House could impeach him for obstructing Congress while matters of executive privilege and presidential immunity were in the process of being resolved by the third branch of our government — the judiciary. And then, on top of that, the basis for proceeding expeditiously with impeachment while those matters were still being litigated in the federal courts was that the President’s behavior — in the view of only that partisan majority — represented such a clear and present danger to the country that no further delay could be countenanced.

Yet, what has happened since? House Speaker Nancy Pelosi has held the articles hostage from the Senate for what will likely be close to a month for partisan political advantage. So much for the argument that proceeding with all deliberate speed was paramount and in the country’s best interest.

At any rate, now that Speaker Pelosi has announced her intention to transmit the articles of impeachment, we can expect to see a Senate resolution outlining how the trial will proceed.

[ad_2]

Source link