[ad_1]

DETROIT ― Melanie Rayford, 18, plans to study software engineering when she enters college this fall. It’s a notoriously unwelcoming field for women of color, but she’s ready for it. Ideas for apps are already popping into her head, like one to streamline route planning for student bus systems.

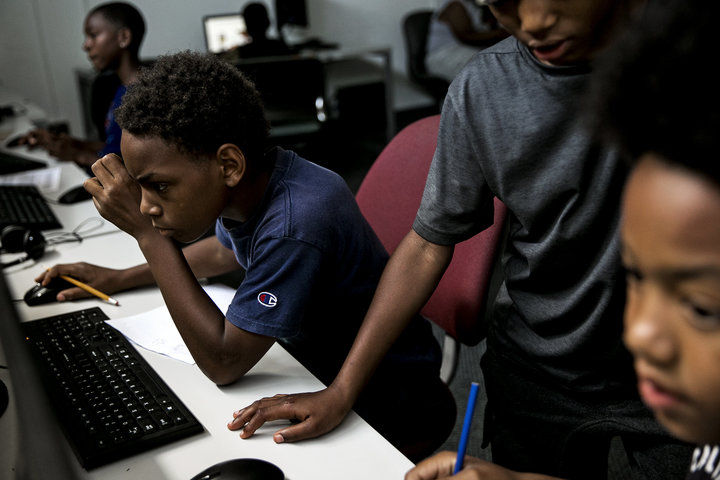

A few hours each day, in addition to her usual classes at one of the city’s top public high schools, Rayford attends an academic and athletic youth program. She’s taken several tech-focused workshops at the nonprofit Downtown Boxing Gym, located on a stretch of road where many of the buildings have been torn down and greenery is reclaiming the empty spaces.

In addition to teaching kids proper combat footwork and punching techniques, the gym also offers free programs for academic achievement and career readiness. It’s where Rayford learned how to set up a wireless network, take apart a computer and test out a 3-D printer. She was failing math when she started at the gym as a sophomore; a tutor helped pull up her scores.

Rayford still occasionally trains with a boxing coach, but most days she heads straight to the gym’s computer lab to do homework or write scholarship essays. With no computer at home and unreliable internet, every minute counts.

If she doesn’t finish her schoolwork at the gym, she’ll set up shop on a computer at Cass Technical High School, occasionally skipping a class to complete an assignment for another teacher. There are other obstacles: A recent project required Microsoft Word, but the school had stopped paying for the software. So Rayford figured out a workaround, Google Docs, which she now uses to tap out essays on her phone at night.

“Everything is so zoomed in, and it’s harder to spell-check and make sure your paragraphs are spaced right,” she told HuffPost. “You know what you’re doing on a computer, compared to a phone.”

Cobbling together computer time frustrates Rayford, but it’s an ordinary burden for students in Detroit. The largely African-American city of 675,000 has the lowest rate of internet connection in the country. Nearly 40 percent of households have no home internet and more than 15 percent only have cellular data plans, according to U.S. census estimates. Twenty percent have no computer or smartphone. (Nationwide, 5 million school-age kids don’t have internet at home, according to the Pew Research Center.)

Recent research in Detroit indicates that most teens have some kind of access to the internet ― but far fewer have reliable internet and computers at home. Many students have more tenuous connections, relying on schools and libraries to get online, or else hopping on and off public WiFi connections from their mobile phones.

As technology becomes increasingly essential for achievement and employment tasks, advocates worry Detroit’s digital divide shuts students out of opportunities they desperately need ― most kids live in poverty, and young adult unemployment is more than double the national rate.

Connectivity is “the gateway to so many pieces of life and the economy that the lack of access to internet is really contributing to many of the disparities that we see in urban areas,” said Vernice Anthony, interim chief executive of Focus: Hope. The civil rights nonprofit offers education programs and job training, including information technology certifications.

National figures gloss over the real divide in Detroit’s internet ecosystem, Michigan State University researchers suggested in a January report. Instead of a total lack of internet access, they see a “mobile-only divide.” They mailed surveys about internet use to more than 500 residents in three neighborhoods. Nearly all respondents reported using the internet, which surprised William Dutton, MSU professor of media and information policy and co-author of the report. Dutton told HuffPost he was specifically impressed by teens’ ingenious strategies for getting online ― whether tracking public locations with open networks or befriending classmates with WiFi at home.

Nearly half the residents in the survey said they primarily used the internet on their phones. Many of them, particularly teens, don’t see that as a disadvantage ― but those users, with limited device capabilities and data caps, were less likely to report “productive” uses, such as homework and job searches.

“The strong dependence on mobile phones ― while it mitigates some of the worst digital divides somewhat ― may be holding Detroiters back,” the report warns.

Bridging the digital divide isn’t just about providing cheap, fast internet. Computer access matters, as Dutton explained. And tools aren’t that useful if students aren’t taught how to use them.

Qumisha “Q” Goss, who runs tech programs at the Parkman library branch near Focus: Hope, said adults often overlook kids’ digital literacy, assuming they’ll intuit technology they grew up with. But when students, who can be experts in social media, use library computers for school, she finds, they’re unfamiliar with basics like how to fill out a spreadsheet or how to double-space a document.

“That part is kind of heartbreaking for me, because I feel like they’re being neglected,” Goss said.

One of the classes Goss developed is Parkman Coders. She’s taught kids programming with Minecraft, a popular computer game, and by using cheap, cutting-edge hardware built for learning, like Raspberry Pi mini-computers and micro:bits. When former students rack up fees on overdue coding books, Goss is happy to forgive their fines.

Parkman and the Downtown Boxing Gym ignite some students’ untapped passion for tech and give useful digital skills to more. Of the 300 kids who have gone through the gym’s youth learning program, all have graduated high school, compared with a 78 percent graduation rate in Detroit’s public school district last year. And Parkman has students returning summer after summer for the coding programs.

A smattering of other local organizations are doing similar work or expanding digital equity. However, community programs ultimately serve only a fraction of Detroit’s disconnected students. (The gym currently serves 185 kids but has more than 800 on its waiting list.) Closing the digital divide on a broader level is more challenging.

Nine years ago, Focus: Hope and other partners taught computer skills to 6,000 residents, gave out thousands of discounted computers and worked with an initiative that brought free broadband to a few hundred people. Despite the program’s impact, it ended when federal funding dried up, and residents lost internet after the service provider went bankrupt.

Internet providers help some get past the cost hurdle, with $10 monthly plans for low-income families. One in 20 residents gets internet through Comcast Essentials, which also offers cheap laptops, free routers and classes. However, the program’s slow speeds still leave users behind national standards ― it offers subscribers download speeds of 15 megabits per second, lower than the 25 mbps definition for broadband internet used by the Federal Communications Commission. Focus: Hope tried to help people sign up for Comcast Essentials but ended its initiative due to lack of interest ― residents were turned off by the rigorous application requirements.

The failure of major internet providers to close the coverage gap spurred a grassroots movement, the Equitable Internet Initiative, in which local residents have built wireless networks serving dozens of families in three neighborhoods.

Community efforts could move the needle more if organizers collaborated and shared their knowledge, Goss and others said, and the city needs to take the lead on tackling the digital divide across all neighborhoods. Officials reportedly plan to release recommendations to expand internet access soon. The school district is also looking to improve digital learning.

Rayford aims to become one of those collaborators. She’s already envisioning what comes after her high school graduation: She’ll attend Wayne State University’s College of Engineering in Detroit and then plans to start a business using her engineering skills. Later she’ll give back by launching a community organization inspired by her grandmother ― who died of complications from alcoholism ― to support teen girls struggling with mental health issues. Rayford wants to teach them tech skills, unlocking the same doors for them that she’s walked through already.

For more content and to be part of the “This New World” community, join our Facebook Group.

HuffPost’s “This New World” series is funded by Partners for a New Economy and the Kendeda Fund. All content is editorially independent, with no influence or input from the foundations. If you’d like to contribute a post to the editorial series, send an email to: [email protected]

[ad_2]

Source link