[ad_1]

Illustration: Damon Dahlen/HuffPost; Photos: Getty

“Farewell To…” is an end-of-decade series that explores some of the biggest cultural trends of the last 10 years. HuffPost’s culture team says bye to the celebrity feminist litmus test, so long to lily-white and mostly male literary institutions, RIP to some of our favorite internet-famous animals and more.

A fresh decade offers fresh beginnings, but on Dec. 31, 2009, mere hours before a new one dawned, we suffered an untimely death. That was the day Disney finalized its $4 billion acquisition of Marvel Entertainment, gaining thousands of established comic-book characters to be recycled in perpetuity — a transaction that would reshape Hollywood as we knew it.

Just like that, the longstanding movie-star era perished. The “cinematic universe” took its place.

Stars still exist, sure. Sometimes they appear in movies. Every now and then, those movies earn large profits. But the concept of the movie star as a linchpin of American culture has diminished, taking a lot else with it.

Over the course of the 2010s, to varying degrees, the major studios — Disney, Warner Bros., Sony, Fox, Universal and Paramount — stopped prioritizing traditional stars, meaning those rarified big-screen specimens who appeal to audiences, time and again, on their own merits. Movie stars can carry projects not tied to enduring franchises, capture the zeitgeist through sheer likability and demonstrate a willingness to play the celebrity game.

But with Marvel and its ilk monopolizing corporate entertainment, the brand is the star. What now drives popular media, at the expense of actors, are fantastic beasts, Baby Yoda and the ever-morphing Avengers roster. (Ask five people to name two Chris Evans roles that aren’t Captain America or the Human Torch. Go ahead, I’ll wait.) And now that platforms like YouTube, Instagram and TikTok have democratized fame, movie stars can no longer claim supremacy, which says more than we realize about the world we live in.

For my money, this marks the decade’s greatest cultural casualty, a deficit that will continue to swell in the 2020s. Hollywood now elevates products over human beings, capital over craft.

When an actor inhabits a range of resonant characters that aren’t merely culled from a preexisting catalog or cooked up as marketing ploys, we pay witness to the dimensions of a single person and, in turn, the larger world surrounding them. A business built on those performers can at least pretend that commerce isn’t the only thing driving it. One that exists to perpetuate trademarks pitched at “fans,” rather than to tell stories aimed at “viewers,” cannot.

Disney doesn’t deserve the entire blame, but that New Year’s Eve in 2009 was more fateful than anyone could have anticipated.

A Hollywood once organized around heavyweights like Joan Crawford, Robert Redford and Will Smith now favors intellectual property in which specific actors are largely beside the point. People don’t go to see “the new Julia Roberts movie” anymore; forget trying to find the next Whoopi Goldberg or Jim Carrey to act as our united funny bone.

This decade seems to have produced fewer certifiable movie stars than any other since the 1920s. Jennifer Lawrence was crowned America’s latest sweetheart, but she hasn’t had a hit since 2016. Melissa McCarthy and Kevin Hart are rare headliners not baptized via franchises, but they’ve suffered diminishing returns. Dwayne Johnson used his “Fast and the Furious” cred to become king of the action blockbuster, but he did so on the shoulders of a multimillion-dollar pro-wrestling career. Scene-stealer Octavia Spencer won a supporting-actress Oscar in 2011, yet she wasn’t given a lead role until 2019. Veterans like Sandra Bullock, George Clooney and Matthew McConaughey found intermittent success, but the adult-oriented movies that define their careers have grown passé. Many other top-paid performers — Robert Downey Jr., Scarlett Johansson, Chris Hemsworth — owe the bulk of their prosperity to comic-book adaptations that essentially sell themselves. Leonardo DiCaprio is arguably the only actor, male or female, to weather this decade without yielding to any of its demands.

To comprehend a landscape in which the movie star is an endangered species, we have to look at what propelled this encroaching extinction.

Movie stars prevailed for the better part of a century, sustained by a populace hungry for luminaries to feast upon. Early silent films didn’t feature credits, so spectators wrote to studios begging to know who they were watching. Yes, the technology was impressive and the stories were (often) compelling, but movies were nothing without the pull of the people on screen. A nascent Hollywood made actors its figureheads.

From the 1920s to the early 2000s, the movie star as a concept remained fairly untouched. The contract-based studio system came and went, but actors remained deities. They drove business and encouraged the public to ogle their every move. The flourishing magazine industry and expanding talk-show scene placed stars in living rooms, where they played the part of glamorous friend.

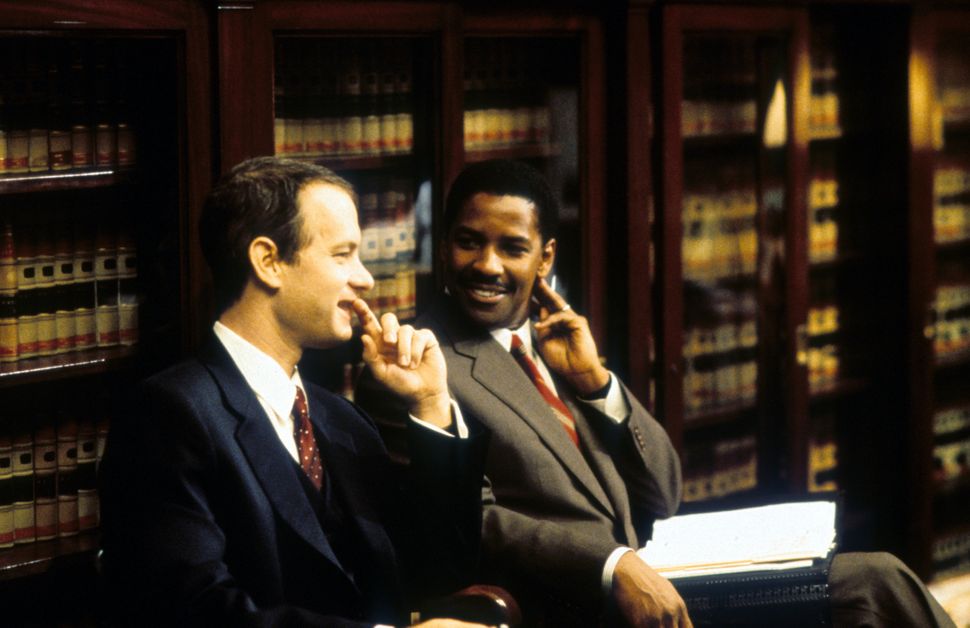

Onscreen and off, the performers we gravitated to revealed something about our desires, our worldviews, what attracted and repelled us, and our collective race- and gender-based hangups. Movie fame became a continuum, constantly commenting on itself: Tom Hanks picked up where James Stewart left off, Meryl Streep assumed Katharine Hepburn’s throne, Denzel Washington became the next Sidney Poitier. Whatever economic shifts befell Hollywood across the 20th century, stardom stayed solvent.

And then it started to change. In the wake of the Sept. 11 attacks, mainstream films became increasingly risk-averse, leading to the rise of the homogenous superhero genre and those hyper-capitalistic “cinematic universes.” After the 2008 financial recession, studios didn’t want to pay A-listers the massive salaries they’d grown accustomed to (some expected upwards of $10 million per movie), even though budgets soared to accommodate elaborate visual effects. Mid-budget crowd-pleasers (think “The Sting,” “Ghost” and “Jerry Maguire”) began to disappear, owing in part to waning VHS and DVD revenue, which had funneled extra cash to studio treasuries.

At the same time, the gargantuan success of 2008’s “Iron Man” led to Disney purchasing Marvel (plus the “Star Wars” factory Lucasfilm in 2012 and 20th Century Fox in 2019). Hollywood faced its biggest overhaul since the inception of sound. Nothing was the same. First-rate actors looking for original material gravitated to smaller screens, where a glut of content is now congesting the marketplace. As television’s renaissance gave way to the streaming craze, only tentpole films (a “Harry Potter” sequel or prequel here, a live-action “Beauty and the Beast” there, Marvel everywhere) are guaranteed to turn profits anymore.

There is little sense of discovery left, and moviegoing in America has lost its luster. When films are designed to be sequelized, what that really means is that they are designed to be remade. Most sequels, threequels and so forth offer a slight variation on the first installment’s plot, so character arcs have to rise, fall and rise again. Actors can’t explore the full range of experience when everything just builds toward a crossover or a cliffhanger or some other canned half-ending. Furthermore, green-screen sets are inherently unworldly. There’s nothing wrong with a well-made blockbuster, but most of them aren’t very well made. What Anne Hathaway gets to do in “Alice in Wonderland” is nowhere near as rich as what she got to do in “The Princess Diaries” or “Brokeback Mountain,” but would a leading studio even greenlight those titles nowadays?

Meanwhile, social media has murdered our attention spans and spawned an exasperating breed of postmodern celebrity known as the influencer. The glow of traditional fame inadvertently fostered a reality in which everybody wants a brush of glory. As calculated and image-obsessed as most talent-driven celebrities can be, our connection to them means that we are engaging with phenomena outside ourselves. Those beautiful images projected onto screens and the emotions they generate color the world that exists beyond the multiplex. Microfame, on the other hand, does the opposite. Generated principally from smartphone apps and internet video platforms, it centralizes a quasi-unfiltered selfhood, convincing everyone that their existence — widely followed or not — is the nucleus from which all else stems. Instead of trying to relate to others, we want others to relate to us. Movie stars don’t fit that calculus.

What will we lose in the coming years without those stars evolving for our edification and enjoyment? With studios’ output becoming more digital and less earthly? With movies serving as fast-paced sensory assaults that maximize noise and minimize everyday humans?

“When we were content to gaze up at movie stars on a screen that seemed bigger than life, the exchange was fairly simple,” critic Ty Burr wrote in “Gods Like Us,” his vigorous history of movie stardom, published in 2012. “We paid money to watch our daily dilemmas acted out on a dreamlike stage, with ourselves recast as people who were prettier, smarter, tougher, or just not as scared. The stories illustrated the dangers of ambition, the ecstasies of falling in love, the sheer delight of song and dance. … We want the stars, but we want what they have even more.”

But now we don’t want the stars, at least not like we used to. If the trend continues, we won’t get to grow old with matinee idols, watching them withstand time like the rest of us. Bette Davis’ eyes, Kathleen Turner’s voice, Eddie Murphy’s laugh: those are all hallmarks of the past, attributes popularized by their owners’ innate charisma. They were built on personalities, not plot devices. Such audience bonds are reaching their sell-by date. Let’s not cry for the multimillionaires, of course; let’s cry for the infantilization of Western entertainment and the circumstances that make our childhood sensibilities more appealing than anything grounded in the real world.

It’s particularly crushing to have suffered this decline right as Hollywood finally started bolstering people of color, queer folks and other underrepresented demographics. At last, American pop culture is remedying inclusivity gaps (and banishing predators). Depressingly, there are fewer original movies released nationwide to showcase all that talent. Michael B. Jordan was great as the complicated supervillain Killmonger in “Black Panther,” but any up-and-comer could have been slotted into that role, first introduced in the Marvel comics 45 years prior. There’s little that makes it distinctly his. I worry a generation of diverse actors will suffer the same interchangeability, no matter how good they look on the cover of GQ.

Our relationships with actors have waned. “Ghostbusters” retreads and semiannual “Batman” repeats can’t rectify that. As far as movies go, our humanity is shrinking. The gods are gone.

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link