[ad_1]

Illustration: Damon Dahlen/HuffPost; Photos: Amazon/Getty

“Farewell To…” is an end-of-decade series that explores some of the biggest cultural trends of the last 10 years. HuffPost’s culture team says bye to the celebrity feminist litmus test, so long to some of our favorite internet-famous animals, RIP to the movie star and looks ahead for what’s to come.

At the dawn of this decade — Aug. 31, 2010, to be precise — Jonathan Franzen’s sprawling novel “Freedom” was published to the orgasmic applause of the literary establishment. His face, veiled in chiaroscuro, appeared on the cover of Time Magazine next to the words “Great American Novelist.” The New York Times published multiple rave reviews.

Then the wave of adulation crashed on a rocky shore. Before the book itself had even gone on sale, technically speaking, best-selling but critically little-regarded authors Jodi Picoult and Jennifer Weiner tweeted their exhaustion with white men like Franzen being celebrated as “literary darlings” by institutions like the Times. Weiner even coined a hashtag more catchy than it was translatable: “Franzenfreude,” she tweeted, “is taking pain in the multiple and copious reviews being showered on Jonathan Franzen.”

Though Franzen’s book was a bestseller and one of the most acclaimed novels of the year, his coronation as the American bard was squelched by the backlash.

2010, it seemed, was the year the whole book world strapped in for a serious debate about whether the most illustrious literary publications had a misogyny problem. Endless blogs and essays were published on “Franzenfreude,” many grappling sincerely with the evidence that female authors were harmed by sexism in review coverage.

“It hardly seems like a coincidence that when a generation of celebrated novelists dies out (Bellow, Mailer, Updike), the new ones anointed are typically white men,” wrote Meghan O’Rourke in Slate. “When Zadie Smith — whose work occupies a similar literary space to Franzen’s, at once engaged by the domestic and the social — is on the cover of the Times and Time, perhaps women writers can start to feel differently.”

At around the same time, VIDA, an organization founded by Cate Marvin, Erin Belieu and Ann Townsend in 2009, released its first report on gender representation in literary publications. It found that the numbers — in terms of bylines and authorship of books reviewed — skewed severely male. The data and the outrage were aligned, and yet what followed is nonetheless surprising: People and publications changed.

Since 2010, VIDA has published an annual report, which, as the years pass, shows that the number of female authors in literary publications is inching upward.

“There definitely seems to have been some progress, overall,” Sara Iacovelli, the VIDA Count director and president of the board of directors, told HuffPost in an email. A decade ago, for example, The New York Times Book Review had an overall gender split of 37.5% women and 62.5% men; in 2018, the most recent count, the percentage of women was up to 48%.

Iacovelli cautioned against too much optimism over the past decade’s results. Of the Times, for example, she noted that for all its topline improvement since 2010, “those nine years it fluctuated up and down a bit, and still never crossed the 50% threshold. For all that’s happened since 2010, it’s hard to applaud such a small uptick as a step towards inclusivity.”

Instead of one or two exceptional writers who depart from the white male norm, the 2010s have seen a more diverse mixture of star authors.

Still, there’s evidence that the needle has moved. Though few publications have reached parity, the overall trend has been a shift in that direction. Even the dismal New York Review of Books stats (27.1% women in 2018) have shown an almost twofold improvement over 2010 (16.2%).

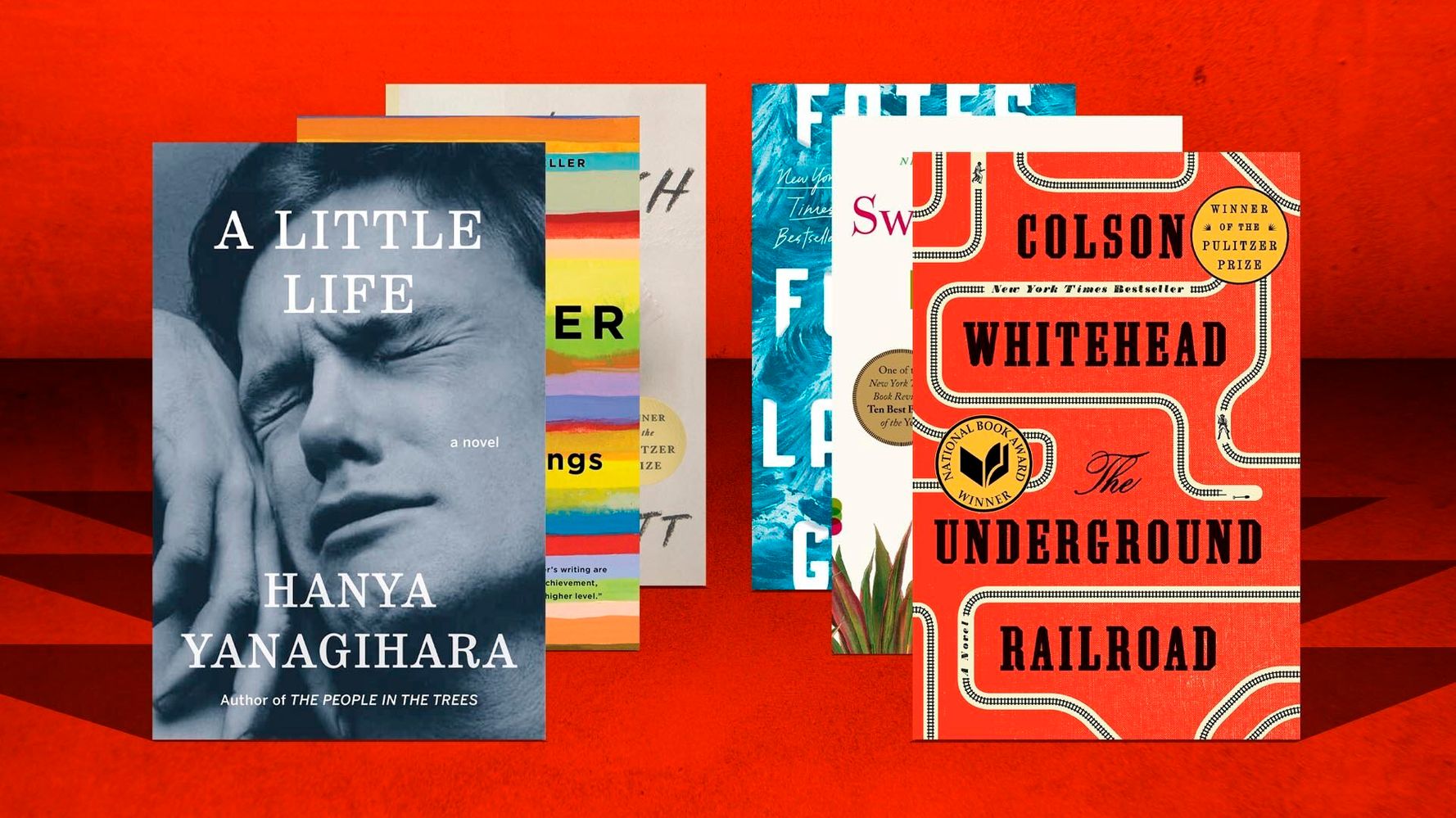

Instead of one or two exceptional writers who depart from the white male norm, the 2010s have seen a more diverse mixture of star authors. Women including Donna Tartt (“The Goldfinch”) and Hanya Yanagihara (“A Little Life”) were hailed for their sprawling, ambitious novels; critics buzzed about Lauren Groff’s “Fates and Furies,” Colson Whitehead’s “The Underground Railroad,” Karen Russell’s “Swamplandia!” and Meg Wolitzer’s “The Interestings” and “The Female Persuasion.”

Perhaps the most high-profile author of the decade, Elena Ferrante, is neither a man nor, in fact, American. Not all of these authors have been universally embraced as great, but the pool of writers deemed worthy of consideration as such, by critics and readers alike, has expanded and diversified.

“What was once insular is now unifying,” National Book Foundation director Lisa Lucas told the crowd at the 2019 National Book Awards Gala, where the fiction, nonfiction, and poetry honors all went to writers of color. “What was once exclusive is now inclusive.”

Lucas took over the foundation in 2016, at a time when the high-profile awards had a somewhat checkered record with representation. Though historically the honorees had skewed heavily white and male, that began to change around 2010. (However, there had been some other recent embarrassments, like 2014 host Daniel Handler’s racist jokes following author Jacqueline Woodson’s win for “Brown Girl Dreaming.”) Lucas, the first woman and person of color to helm the foundation, made representation and inclusivity a focus of her messaging. When looking back at the past decade, she told HuffPost in an interview, a multipronged effort to build a more inclusive literary scene has indeed paid dividends.

“A lot of it is scale,” Lucas said, pointing out that Toni Morrison and Ralph Ellison had won National Book Awards for fiction in prior decades. Now these wins aren’t exceptions in a sea of white male honorees. The main difference over the past decade, she argued, is that “we’ve gotten to a place where I feel like it’s not shocking to see.”

Of the past 10 National Book Awards for fiction, six have gone to women and seven to writers of color, including two wins for novelist Jesmyn Ward. Prior to Jaimy Gordon’s 2010 win for “Lord of Misrule,” the past five fiction awards had gone to white men. Until Ward’s first win in 2011, the last to go to an author of color was the 1999 award, presented to Ha Jin for “Waiting.”

Lucas insists that this dramatic shift is not the result of a top-down directive, but has grown organically from assembling thoughtful, diverse panels of judges and from broader trends in the literary industry. She suggested that innumerable factors are at work in driving those trends, starting with the hard work of past generations.

“I grew up reading Toni Morrison and having it valued in my home. And I wanted to work in books eventually, because I fell in love with literature,” she said. “A generation that grows up with people who are writing in the ’70s and ’80s, having access to more work than we might have in the ’50s or ’60s, or ’40s or ’30s, is going to change who is interested in doing the work, just because it feels relevant.”

Morrison herself, in addition to being one of the most widely acknowledged great American novelists, was an advocate for Black authors, ushering many into print in the course of her career as an editor at Random House in the late 1960s and 1970s. “I wanted to give back something,” she told Hilton Als in 2003. “I wasn’t marching. I didn’t go to anything. I didn’t join anything. But I could make sure there was a published record of those who did march and did put themselves on the line.”

Lucas pointed to the presence of more people of color and women in influential positions — on university faculties, in powerful roles in publishing, on awards committees, writing for media outlets — as a force in expanding who is encouraged and recognized.

Some of the very institutions targeted for critique by VIDA and other advocates have changed leadership, perhaps partially in response. Lucas, then the publisher of arts journal Guernica, was tapped to head the National Book Foundation in 2016 after advising a recruiter to consider a woman or person of color to replace the departing director. Pamela Paul, who took over at The New York Times Book Review in 2013, has expressed that it’s a priority for her publication’s pages to be gender-balanced and racially diverse.

Lucas also argued that readers have been hungry for books reflecting the multiplicity of human experience and have rewarded publishers for devoting more resources to them. “The arts have to stay in business, whether it’s a nonprofit arts institution or a for-profit arts organization,” she said, adding that over the past decade, arts nonprofits and the publishing industry both came to realize “that there’s a big hole artistically, that people are not being served well.”

After all, it’s long been accepted that women read more than men, and a 2014 Pew survey also found (if only by a statistically insignificant margin) that Black Americans read more than white ones. It stands to reason that readers would be responsive when publishers started seeking out and promoting more great fiction by and about people whose lives resemble the lives of their readers, rather than sticking with white men.

“Obviously there’s always been work produced by people of color,” she pointed out. “It’s not like they weren’t there. I think what happens is you also realize their value over the course of the past 10 years, and when you realize something’s value, you get more of it and you get more of a machine under it that can support and include it.”

And yet it took many decades to get there. “When I think about the year 2009 and the person that I individually was and the way that I understood the world that I lived in, versus 2019, we have had a real reckoning,” Lucas said. “I think that reckoning seems fast and sharp, because it’s like all of a sudden we’re considering all these things we haven’t considered for quite some time. But it was a slog. It was a lot of people doing very hard, uphill work for a very long time.”

I think that reckoning seems fast and sharp, because it’s like all of a sudden we’re considering all these things we haven’t considered for quite some time. But it was a slog.

National Book Foundation director Lisa Lucas

If decades of work really began to pay off in the past decade, it’s worth asking: Why now? To some degree, it was perhaps simply a tipping point, a culmination of many years of underrecognized work. The media ecosystem of the 2010s — a confluence of concerted activism and empowerment-porn digital media trends — likely played a role as well. Blogs and startup outlets, many staffed by young women and people of color, found an audience hungry for ongoing coverage of cultural imbalances.

The initial wave of Franzenfreude passed, of course, but Franzen remained a target of bitter bloggers and readers. His 2015 novel “Purity” was largely well-reviewed (though not, full disclosure, by me), but the lingering distaste for what he represented had been kept so fresh in the public mind that it would have seemed ludicrous to once again present him as the greatest working American novelist. By then, he was simply one among many.

In the initial response to Weiner and Picoult’s critiques, Chris Jackson, executive editor of publishing imprint Spiegel and Grau at the time, wrote a blog expressing his embarrassment that he didn’t read as much fiction by women as by men — that, in fact, in a conversation with a fellow editor, he’d been unable to immediately recall a novel he’d read by a woman recently. Already an ardent advocate for diversity in publishing, he admitted that “apparently I’ve been ignoring the literary output of half the human population.” He announced that he’d committed to reading one book by a woman for every book he read by a man. He’s now the publisher and editor-in-chief of Random House’s One World imprint, which publishes a race- and gender-diverse list of authors and makes “represent[ing] voices from across the spectrum of humanity” part of its mission statement.

Jackson’s “reading women” challenge became a genre in itself. Bloggers published essays about their years of reading only women or writers of color or international writers and wrote listicles of books by women or writers of color or international writers or queer writers that everyone should read before turning 30. News outlets published endless takes about the state of things, questioning whether staid institutions were doing enough to bring nonwhite, nonmale writers to the table.

The content cycle was fueled by reports from organizations like VIDA and the continued efforts of activists. The scrappy, clickbaity, deeply flawed digital journalism model of the decade lent itself better to democratizing acclaim and to shredding hidebound norms than it did to enshrining new Great American Novelists with reverential profiles.

Among the flaws of this model, and indeed of some of the activism that it sprang from, was that it contained its own glaring structural inequities. Literary media and, in particular, the publishing industry have long employed plenty of white women, though often in lower-level roles. With the advent of the VIDA Count and the Franzenfreude complaints, many were eager to finally focus attention on the obstacles faced by women writers, while mostly ignoring still higher obstacles placed in the way of writers of color, LGBTQ writers and writers at the intersection of these identities.

But activism around the whiteness of book publishing began to break through to the mainstream discourse as well. In a 2014 New Yorker essay, “MFA vs. POC,” acclaimed Dominican-American author Junot Díaz blasted American MFA programs for their homogeneity and the damage it inflicted on students of color. “In my workshop,” wrote Díaz, who attended Cornell University’s MFA program, “the default subject position of reading and writing—of Literature with a capital L—was white, straight and male. […] In my workshop what was defended was not the writing of people of color but the right of the white writer to write about people of color without considering the critiques of people of color.”

At around the same time, the eminent and prolific children’s book author Walter Dean Myers took to the pages of The New York Times to ask, “Where Are the People of Color in Children’s Books?” Myers wrote movingly about his own childhood as a voracious reader, the revelation that was discovering James Baldwin as a teenager, and his own efforts to write books that Black children could see themselves in.

“In 1969, when I first entered the world of writing children’s literature, the field was nearly empty,” Myers wrote. “Children of color were not represented, nor were children from the lower economic classes. Today, when about 40 percent of public school students nationwide are black and Latino, the disparity of representation is even more egregious. In the middle of the night I ask myself if anyone really cares.”

It seemed as if many decision-makers, at least, did not care. Myers’ essay was pegged to a study from the Cooperative Children’s Book Center at the University of Wisconsin, which found that of the 3,200 books the center received in 2013, only 94 were about Black characters.

Not long after, BookExpo America announced the panel lineups for its first BookCon. The Blockbuster Reads panel, which featured what Publishers Weekly called “an all-star panel of children’s authors,” was composed of only white men. The rest of the announced panels were also entirely white. In response, authors and activists launched a viral hashtag, #WeNeedDiverseBooks, to draw attention to the whiteness of children’s book publishing.

Finally, the event company behind BookCon, ReedPop, responded that it would add more diversity to that year’s lineup; as part of this compensatory effort, it added a panel called “The World Agrees: #WeNeedDiverseBooks.” Ellen Oh, one of the authors behind the hashtag, later co-founded an organization named We Need Diverse Books, which spread its advocacy into a number of avenues, including awarding grants, publishing anthologies and coordinating mentorships.

But it wasn’t just the hoary old-white-men institutions of publishing that harbored these blind spots. In a 2012 Rumpus piece, Roxane Gay published a survey of the race and gender of authors reviewed in The New York Times the previous year. She opened by musing that, observing the efforts of VIDA and Jennifer Weiner to track gender inequity, she’d wondered when race would be given such close attention. “Race,” she observed, “often gets lost in the gender conversation as if it’s an issue we’ll get to later.” Her conclusions were grim: Roughly 88% of the authors reviewed in 2011 were white.

In its 2014 report, the VIDA Count finally added a Women of Color report, though with many caveats about its incomplete dataset, which was gathered through surveys sent to writers. Two years later, it added information about age, disability and education level. “As we’ve grown,” Iacovelli told HuffPost, “we’ve worked to make the VIDA Count more intersectional, and to decenter white cis women from the narrative about who’s ‘missing’ from prestigious pubs.”

“If you want to build a better book world,” she wrote, “you have to think intersectionally.”

While we have seen a recent increase in awards given to women and people of color, and an increase in bylines and books reviewed by women … that doesn’t negate a long history of gatekeeping, and it doesn’t necessarily signify a permanent change.

VIDA Count director Sara Iacovelli

All this work, as spotty and inconsistent as it was, does seem to have gotten us somewhere. It’s almost strange now to remember that at the beginning of this decade, there seemed to be more celebrated novelists in America named Jonathan than there were celebrated novelists who were women: Jonathan Franzen, Jonathan Safran Foer, Jonathan Lethem. Our literary wunderkinder were young white men hungry for laurels; our literary sages were aging white men who waited by the phone each year for a call from the Nobel Committee.

Sure, The New York Times may have recently called poet and novelist Ben Lerner “the most talented writer of his generation.” It’s hardly enraging when, if anything, the fanfare surrounding his latest novel, “The Topeka School,” has been more muted than the laudatory coverage of Irish novelist Sally Rooney. The Times labeled her “the first great millennial author” in an August 2018 headline.

But a decade is hardly enough to solve such entrenched problems, even if the progress seems striking. We have not arrived at a literary utopia. “While we have seen a recent increase in awards given to women and people of color, and an increase in bylines and books reviewed by women in many of the publications we count, that doesn’t negate a long history of gatekeeping, and it doesn’t necessarily signify a permanent change,” Iacovelli told HuffPost.

What comes next, unfortunately, may be still more difficult than eking out the changes we’ve seen thus far. Much of the publishing industry remains the same; media and activist criticism may lead editors to consider acquiring or assigning review coverage more diversely, but it seems to have done little to change industry working conditions that are unfriendly to nonwhite, nonwealthy people. The vast majority of publishing employees are still white, and wages are still prohibitively low for entry-level positions.

In the children’s book world, awareness about the lack of diversity in the industry seems to have spurred more change in writing about people of color than in writing by people of color. In 2018, CCBC reported that the number of children’s books about Black people had quadrupled from that abysmal 2013 report to 405 (11%). The number of books by Black authors was half the number of books about Black characters: just 202, 5.5% of the books surveyed, were by Black writers. The superficial changes, themselves only partially successful, mask an underbelly that crawls with injustice.

Even the activists and progressive organizations that got us here often disappoint. In 2018, Díaz was accused of misogynistic and sexually inappropriate behavior by multiple women. In March of this year, VIDA announced a change in leadership and plans to “focus inward and re-examine our foundations” after “[i]t had become clear that despite VIDA’s past efforts and intentions, a climate of white feminism with racist, cis-centrist, and ableist overtones was allowed to persist with no accountability measures in place.”

Though a gender count for 2018 was released as usual, the intersectional report was delayed, the new board announced, so that the organization could develop a better survey methodology. “We are an all-volunteer org and there’s a lot that goes into getting this right, so we want to be sure to give it enough time and care,” Iacovelli said.

The book world remains riddled with less visible forms of exclusion and inequity — notably, overwhelmingly white workplaces where microaggressions against people of color are endemic, pay gaps persist and few can even afford to forge a career without a financial safety net. Perhaps the 2020s will see the end of the Standard-Issue White Editor With Family Money. For now, the 2010s may have laid the Great White Male American Novelist to rest, or at least knocked him down a few pegs.

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link