[ad_1]

ARCATA, Calif. ― It was early morning on April 18, 2017, when things went terribly wrong at a college party in this otherwise quiet small town in California’s rural northwestern corner.

Students from Humboldt State University, many of them African American members of Brothers United, a leadership-focused club for male students, had gathered off-campus. More than 100 people were packed into a small one-story house. Everything was fine until a fight over a lost cellphone shoved the celebration toward its bloody conclusion.

A few minutes after the dispute began, 19-year-old David Josiah Lawson, whose friends called him Josiah, was sprawled in the bushes in front of the house, bleeding from stab wounds to his torso. Someone called 911; an ambulance and police were dispatched. The police got there first, within minutes, but attendees said the confusion of the scene seemed to overwhelm the two officers, who focused first on breaking up the party while Lawson bled out a few feet away. Meanwhile, witnesses were dispersing.

One witness, Katauri Thompson, then a Humboldt State freshman who had grown up with Lawson in Southern California, said several of the Black students were standing outside the house yelling at police to pay attention to the injured young man. The loud voices, Thompson said, appeared to intimidate and confuse the officers, neither of whom was Black. One officer tried to use a portable defibrillator to revive Lawson, but the device was inoperable, according to witnesses.

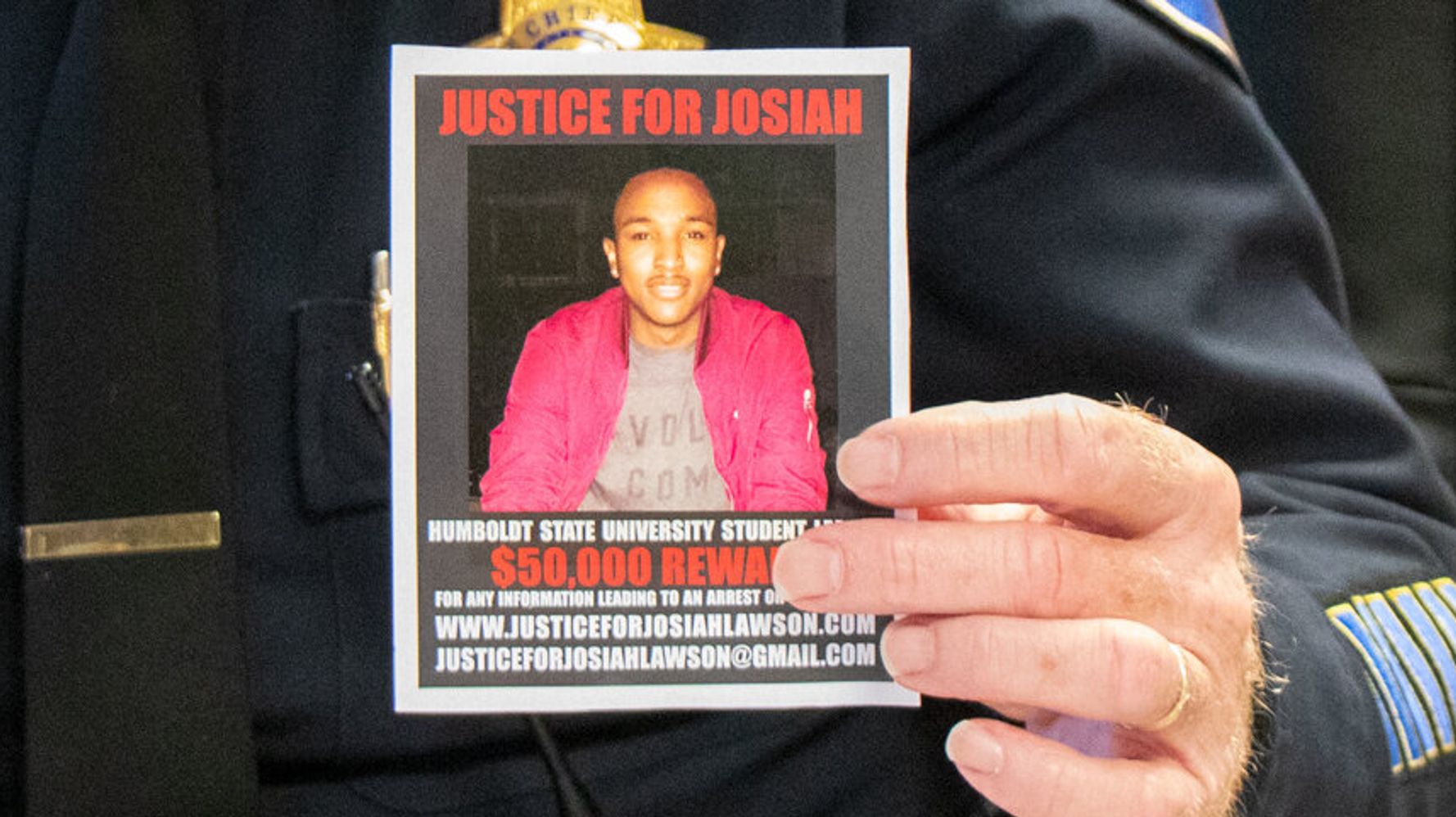

Police arrested a suspect at the scene and prosecutors charged him with murder, but a judge ruled that investigators had not gathered enough evidence to bring him to trial. A grand jury later agreed, declining to indict the same suspect.

Two and a half years after Josiah Lawson’s death, his killing remains unsolved. In November 2018, his mother, Charmaine Lawson, sued the city and the Arcata Police Department, claiming that law enforcement’s response has been incompetent and that investigators have been “unmotivated” to solve the crime because her son was Black.

Chief Brian Ahearn, the city’s third police chief since Lawson’s death, admitted in interviews with HuffPost that the department made some early mistakes during the investigation but said he could not discuss specifics because of the ongoing lawsuit.

Under Resourced And Under Trained

It’s hard to know how often rural murders of Black victims like Lawson go unsolved, but anecdotal evidence suggests the problem is widespread.

The Washington Post reported last year that 75% of the victims of unsolved murders in major U.S. cities in the past decade were Black. But no one appears to have compiled similar data for rural areas, where one-fifth of all Americans live. Just 8% of rural residents are African American, according to the Pew Research Center; that figure is only 1.4% in Humboldt County, per the U.S. Census Bureau.

Arcata, a rural town of 18,000 when the 7,700-student university is in session, had 25 sworn police officers at the time of the 2017 party. Small police departments, especially in remote areas such as Humboldt County, are rarely able to afford the time or money for specialized investigative training or anti-bias courses, experts said.

Most of the country’s police departments have fewer than 10 officers, said William Lally, a former small-town police chief who teaches criminal justice and sociology at Eureka College in Illinois. And if officers take time off to travel to a bigger city for training, it puts a severe strain on their colleagues back home.

As a result, small towns are often unprepared for major crimes or for demographic changes, which can be surprising for officers who grew up in a relatively homogeneous community. And that doesn’t always bode well for people from minority communities, whether they’re victims, witnesses or suspects.

“If you have a lot of white, straight, Christian people and you bring in any group that is a minority, we tend to not only go off these preconceived notions about these people ― we tend to always believe the worst in people,” Lally said.

The concern over police reactions to victims of color comes at a critical time. Lawson was killed in 2017, the same year that hate crimes based on race, ethnicity or ancestry spiked by 18% nationwide, according to the U.S. Department of Justice. It was the third straight year they had increased.

An Investigation Without A Fighting Chance

Back in Arcata, the investigation started to unravel from the moment police first responded around 3 a.m.

Partygoers were streaming out of the small house at the end of the cul-de-sac, which resembles a driveway surrounded by a handful of modest homes more than a street, in a residential area less than a mile from the Humboldt State campus. Several of Lawson’s classmates who attended the party did not respond to HuffPost’s recent interview requests; many have graduated or moved to other parts of the state. But court transcripts provide a look at what happened that night.

Officers allowed partygoers to leave the scene without taking witness statements or checking whether anyone had recorded video of the stabbing ― both of which should have been standard procedure in such a case, experts said.

“I think [the responding officers] were afraid,” said Thomas Parker, a retired FBI agent who spent months investigating the case. Lawson’s mother asked Parker to look into her son’s killing after her lawyer introduced them.

Thompson, not realizing that his friend was the injured victim, said he went home. That’s when he heard from another partygoer that Lawson had been stabbed. Thompson said he immediately left for the hospital. Doctors there told him his friend had died.

Lawson and Thompson had followed nearly identical paths, attending the same schools in both Los Angeles and Riverside counties before choosing Humboldt State, a day’s drive and a world apart from Southern California. Lawson was studying criminology, with plans to go into law and politics. He loved nature, Thompson said, and was skilled at settling arguments.

“He was always peaceful,” Thompson said. “He was a peacemaker.”

Charmaine Lawson, who lives in Moreno Valley in Southern California, said she will be a constant presence in Arcata until her son’s case is solved. She frequently attends vigils and meetings in the area. Ahearn, the police chief, admits that her repeated trips help keep him motivated. In November, the two collaborated to write a press release reminding the public about the investigation, hoping to inspire witnesses to come forward.

In addition, Lawson, who has two other children and works in health care, is trying to set up a nonprofit, Josiah’s House, that would help homeless college students find housing and give students of color a safe place.

“I send my son off to college and he gets murdered and the justice system fails him,” she told HuffPost. “I’m not going anywhere.”

At the scene, police arrested Kyle Zoellner, who had fought with Josiah Lawson in front of the house. Witnesses later testified that Zoellner, who was not a Humboldt State student, and Lawson were wrestling on the lawn. One witness described two quick jabs to Lawson’s abdomen during the fight, although the witness neither saw a knife nor identified Zoellner, according to a court transcript from a preliminary hearing.

Lawson then stumbled across the lawn and fell into the bushes while a partygoer punched Zoellner unconscious.

Zoellner was later charged with Lawson’s murder, but a judge ruled prosecutors had insufficient evidence to bring him to trial, and a grand jury refused to indict him in 2018. Zoellner, who still lives in Humboldt County, declined through his attorney to speak to HuffPost.

A Dead College Kid And No Justice

A few months after the killing, Parker, the retired FBI agent, began his investigation. Months later, he quit in frustration. Parker said that he had never quit another consulting job but that Arcata’s police establishment seemed unwilling to solve the case or the underlying racial problems.

Ahearn said he could not respond to Parker’s claims because of the lawsuit.

Several Black students, most of whom were from the Los Angeles and San Francisco areas, told Parker they were uncomfortable in the overwhelmingly white Humboldt County.

“A succession of police chiefs did not seem to recognize the just-below-the-surface racial considerations that came from the university recruiting these minority students from other parts of California,” Parker told HuffPost. “There seemed to be no interest in addressing any of the racial issues.”

A few months before Lawson’s death, Thompson said he and two other Black students were walking home from the downtown bars when Arcata police officers stopped them. He said they ordered the students to the ground at gunpoint and searched their bags. Officers allegedly told the group they were looking for suspected drug dealers who were believed to be in the area. The incident in liberal Arcata, sometimes called “’60s by the Sea,” surprised Thompson, who figured that race played a part.

Thompson noticed other troubling signs in Humboldt County, including “dirty looks” in restaurants and stores and an inappropriate question from a local teenager: Are gangs real?

“Why would you ask me?” Thompson replied to the teen.

Thompson, who left Humboldt State a year after the killing, said he was traumatized by his friend’s death. He now attends a community college in his Southern California hometown.

Murders overall are more likely to be solved in rural areas, according to national data compiled by Ralph Weisheit, an Illinois State University criminal justice professor and expert on rural crime and justice. Rural police are more likely to know both the victims and the suspects, Weisheit said, making it easier to figure out motives.

But even more rural murders would be cleared with better-trained investigators, he said.

“In these rural areas, it’s a rare event,” said Weisheit. “In many cases, the investigative unit are the same people doing traffic stops.”

Trying To Close A Cold Case

Ahearn, a former San Diego police captain, was hired about a year ago as Arcata’s third police chief since Lawson’s death. A picture of the teenager sits on Ahearn’s desk, next to a note with the number of days the killing has gone unsolved. When HuffPost spoke to him in October, several copies of the Lawson “murder book,” a binder full of evidence and other case materials, sat on a shelf, ready to be distributed to investigators for a fresh look.

“This is not going to be a cold case,” the chief said. “My job is to get this across the finish line.”

Still, Ahearn too has made missteps since taking office, something he acknowledges. Eager to find witnesses, he released pictures from police car cameras of partygoers ― many of them Black college students ― in 2018 and asked them to come forward with new information. Ahearn admits he should have reached out to the local Black community before releasing the photos, but adds that the strategy led police to another party attendee, whom they interviewed.

But the county’s Black community was not happy with the chief’s actions.

“It’s almost this blame-the-victim thing,” said Doug Smith, a Humboldt State alumnus who now runs the university’s African American Center for Academic Excellence, where he said several Black students expressed concern over the photo release. “It’s not a good look.”

Sitting in his office, Ahearn read aloud a handwritten note from a resident concerned about the stagnant investigation. Pushed by angry residents (and perhaps by Charmaine Lawson’s suit), the police department has increased training and hired more Black officers.

One of those new officers, Travis Sherrod, was hired in 2017 after the murder. A former Humboldt State football player who grew up in Southern California and was living in Humboldt County when he was hired, Sherrod said he never thought he would be a police officer but he thought he could make a difference in a town where less than 3% of the residents are Black, far below the state (6.5%) and national (13.4%) figures.

Sherrod said his presence is good for Black students from other parts of California.

“A lot of students feel comfortable speaking to me because I look like them,” he said. “I feel like I have a story I want to pass on.”

In the fall of 2017, the department contracted with Sandra Brown, a former police lieutenant who now works for Fair & Impartial Policing, which trains officers to avoid bias in their job. The instructor, who is Black, said that while she didn’t sense any racism in Arcata, it’s important to provide bias training for police officers.

Indeed, racial attitudes could have compounded the mistakes the night Lawson was killed, she said, although perhaps not any more than in an urban department.

“We might mistake someone who’s talking loudly as being threatening, but that’s all over the country,” Brown said. “I don’t necessarily assume a person from a rural area is going to have a negative bias.”

But Josiah Lawson’s mother feels differently about Arcata, saying her son might still be alive if he had been assaulted in a more diverse area.

“I need students of color to be safe,” she said. “It’s a climate of racism there.”

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link