[ad_1]

What we don’t know is how those votes will shake out. But we have a pretty good sense.

Before we get to how the votes on the two articles of impeachment — abuse of power and obstruction of Congress — will turn out, it’s worth walking through the process that will get us there.

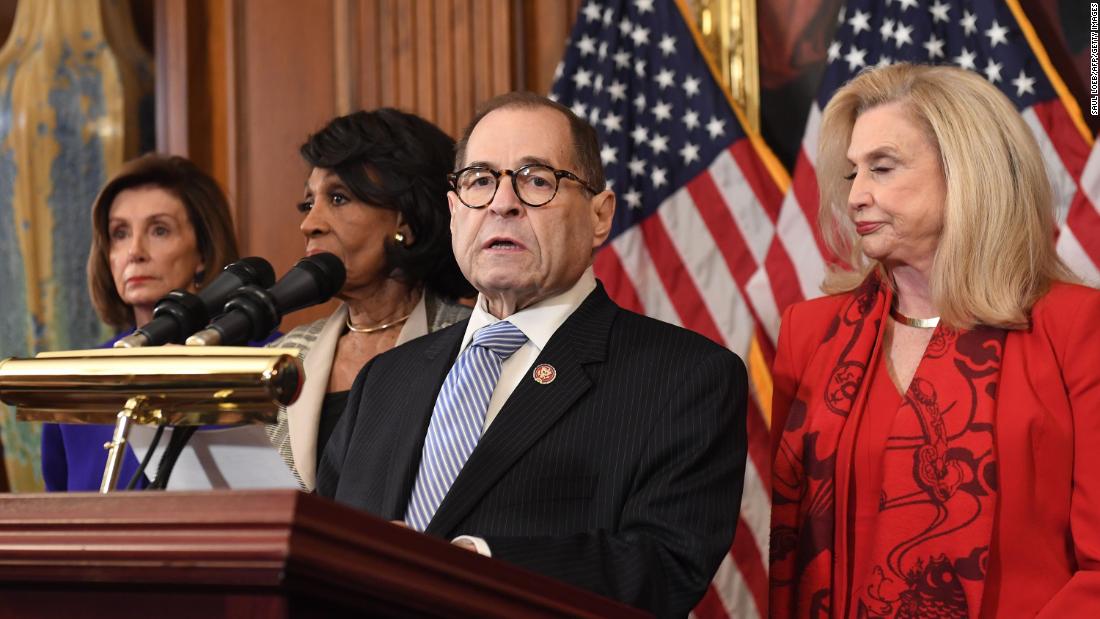

The first step to get the articles of impeachment to vote on the House floor is to pass them through the Judiciary Committee. That is expected to happen by the time Congress leaves for the week — likely Thursday. Because Democrats have a majority on the committee — as they have on every House committee — passing the articles out of committee should be drama-free. (I’d be stunned if there was any Democrat who opposed either of the impeachment articles — and even more stunned if any Republicans on Judiciary voted for either article.)

If all goes to plan, that would put the articles of impeachment on the House floor next week. At which point — and likely before — both sides will do absolutely everything in their power to keep all of their members in line while finding one or two (or more) from the other party to recruit as defectors/rebels.

Even a single vote or three to say that either the support or opposition to impeachment was “bipartisan” would allow a political (and perception) victory to be claimed by the side that was able to convince a few converts.

Might that happen? Yes. Based on what we know now — and recent political history — it’s much more likely that Democratic members break ranks than it is Republicans do the same.

That Republican unity was rightly understood as a major win for Trump who had lobbied hard in the days leading up to the vote to keep any GOP members from crossing party lines. At this historic moment, any sort of Republican rebellion against Trump has the potential to splinter, taking what is a small crack in his support one day and transforming it into a gaping chasm within 24 or 48 hours.

“Prevailing feeling was we were better off with two because the obstruction of justice brought in a whole bunch of things, and it was a mixed bag of tricks, and the consensus was we were better off standing with two rock solidly and not spread ourselves too thin.”

It doesn’t take much reading between the lines there to understand that Democratic leaders poll their caucus on how many of them could be for certain impeachment articles and settled on the two they believed gave them their best chance to avoid any large-scale defections.

Even with that forethought, it seems like as foregone conclusion that at least Van Drew and Peterson, who opposed the formal impeachment vote, will also stand against the history-making attempt to actually impeach Trump.

Van Drew said as much to CNN within the past few days, saying that he would be “no” vote on all articles of impeachment “unless there’s something that I haven’t seen, haven’t heard before.” He added that he believed impeachment was “tearing the nation apart … and I want to bring people together.”

Peterson has been far more reticent to answer questions about his plans on a future impeachment vote. “I don’t have an idea what they’re doing,” he told CNN of his Democratic colleagues handling the impeachment investigation.

The bigger question for Democrats is whether any more of their moderate members or members sitting in districts Trump won in 2016 will feel compelled to vote against one or more of the articles of impeachment.

There are 31 of those seats (represented by a Democrat but that Trump won in 2016) on the ballot in 2020. Peterson and Van Drew represent two of them. That group will be the the focus of both parties’ hard lobbying between now and next week’s vote.

The goal for Democrats is to limit the rebellion to just Van Drew, who seems like a lost cause, and Peterson, who represents a district that Trump won by 30+ points in 2016. If you start to see 10 or more of those Trump-district Democrats crossing the aisle to vote with Republicans, that will be a major blow to the party.

[ad_2]

Source link