[ad_1]

Kevin Guthrie is a self-taught artist who draws portraits of pop-culture heroes and villains with pencil and crayon on the inner side of flattened cardboard boxes once packed with beer cans. The renderings are simple, but they brim with personality and social commentary. Guthrie’s previous exhibition at Julia Martin, “Bicycle Thieves” (2016), was the first in a planned trilogy of shows about the role of sports in American culture. It featured images of the opponents Muhammad Ali faced in his sixty-one professional bouts. The artist’s latest show at the gallery, “June 13, 1972,” commemorated the first Major League Baseball game the artist attended—New York Mets vs. Atlanta Braves on the titular date. Together, the drawings portray every player on the team rosters that spring day at Atlanta Stadium. The players are usually pictured individually, from the shoulders up and with their heads framed by black or white diamonds on colorful backgrounds. The surface of each of these portraits is textured by the uniform impressions of beer cans, and a label written above the player spells out his assignment: LEFT, CATCH, PINCH, PITCH. The white-walled gallery felt like a baseball card swap; you could almost smell the stale bubblegum. But the show also included depictions of politicians, criminals, and seedy entertainers, making it a contradictory portrait of the United States, in which the country’s corruption is evoked along with its wholesome values.

In 1972 Major League Baseball marked the twenty-fifth anniversary of racially integrating its teams. Guthrie’s Riding the pines with Willie Mays and Tug McGraw shows Mays, a black right-handed home run king, in a dugout beside one of his Mets teammates, relief pitcher Tug McGraw, a long-haired white Southerner. Mays chomps on a blade of grass while holding a copy of Playboy. McGraw leans back to put his feet up as a rat scurries beneath the bench.

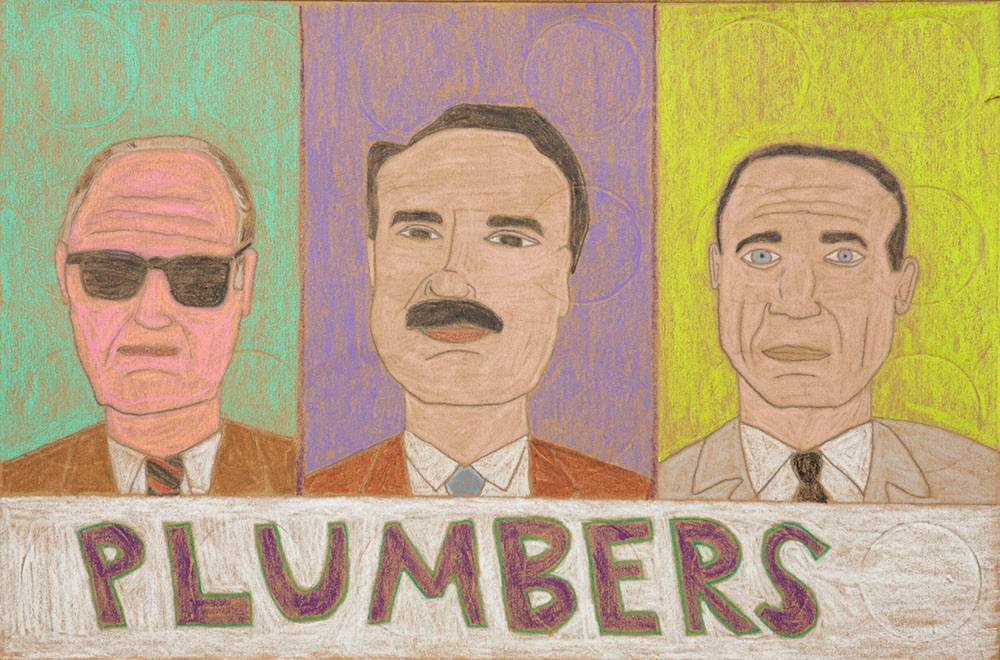

This particular meeting of the Mets and the Braves happened just before the Watergate scandal, which began with the burglary of the Democratic National Committee’s headquarters on June 17, 1972. Guthrie’s These American patriots are going to break into the DNC Watergate offices in four days. No way they get caught pictures E. Howard Hunt, G. Gordon Liddy, and James McCord, the three men convicted of the Watergate break-in. President Nixon directed them to stop leaks of classified information from the White House, and this work’s one-word text label reads, PLUMBERS. These simple drawings could be called cartoons, but Guthrie displays more skill and self-awareness than most so-called outsider artists: he nails McCord’s high hairline, and Liddy’s mustachioed arrogance practically oozes out of the frame.

Other exhibited works depicted the candidates who ran in the contentious 1972 Democratic Party presidential primaries. Portraits of Alabama governor George Wallace and South Dakota senator George McGovern flanked Guthrie’s version of a poster advertising the blockbuster “adults only” film Deep Throat. The porno flick’s title was, famously, the code name that investigative reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein gave their key Watergate informant, thus wryly conflating dirty politics and dirty movies. Guthrie’s juxtaposition of images in “June 13, 1972” further suggested that American political theater is its own kind of vulgar entertainment.

Journalists were calling baseball the “national pastime” by 1856, just five years before the first battle of the Civil War. The sport has long been a force for unity within a divided country. Guthrie’s show, which pitted American ideals against American realities, came in the middle of another baseball season, as our country continued to seethe with debates about racism and executive malfeasance.

This article appears under the title “Kevin Guthrie” in the December 2019 issue, pp. 101–102.

[ad_2]

Source link