[ad_1]

Garth C. Reeves, Sr., The Miami Times’ retired publisher who became the enduring patriarch of a family newspaper dynasty after decades of fighting the political establishment and while guiding the Black community through the city’s racial problems, died on Monday, November 25. He was 100.

Regarded as a titan in the Black Press, Reeves was widely respected in Miami for using his power and influence to advance the agenda of the city’s Black community. After experiencing the pain and humiliation of segregation in parks, schools and the U.S. military, Reeves grew into an uncompromising crusader who smashed racial barriers in some of the most prominent organizations in Miami and the nation.

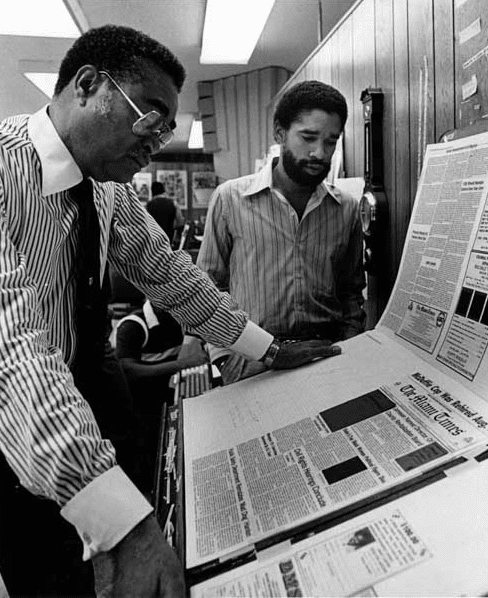

During his lifetime, Reeves’ newspaper got a police chief fired, ended the career of a Miami mayor, supported a boycott that cost Miami Beach’s tourism industry millions, and unapologetically called riots “protests” or rebellions. He stared down Miami’s political establishment that for decades had been accused of shutting out Blacks in government as Hispanics rose to power in the city’s political and business establishments.

He urged his journalists to write from a Black perspective, one that saw the struggle through a different lens than white newspapers.

His newspaper career spanned at least eight decades. At the height of Reeves’ leadership, The Miami Times earned the name, “The Voice of Miami’s Black Community.” One of the last great Black publishers, Reeves’ death closes a significant chapter in The Miami Times’ illustrious history.

Reeves was born February 12, 1919 in Nassau, Bahamas. That same year, Reeves’ father, Harry Ethelbert Sigismund Reeves, moved to Miami where he founded the Magic Printing Company in Overtown, the city’s historic Black, once-thriving neighborhood near downtown. Harry Ethelbert Sigismund Reeves in 1920 founded the Miami Sun, which closed because of a paper shortage during World War I. In 1923, The Miami Times was founded. Reeves was just four years old.

Garth C. Reeves, Sr. was among many Blacks who attended Miami’s esteemed Booker T. Washington Senior High School, the city’s oldest predominately Black high school that was built when students of color were not accepted at white public schools. Black students at Booker T. were given secondhand text books and football gear that came from white schools.

In 1923, Harry Reeves started The Miami Times at NW 8th Street and 3rd Avenue. It would move four more times in the Overtown neighborhood. When Interstate-95 was built through Overtown, it displaced thousands of Blacks. Many fled north to the Liberty City community, where The Miami Times sits at its present location, 900 NW 54 Street.

In 1940, Reeves graduated from Florida A&M University, a major, historically Black school in Tallahassee, FL. In 1942, Reeves was drafted to serve in the Army during World War II. During an interview in 1999, Reeves recalled a trip on a train to the Pacific coast to go overseas. Despite repeated requests, a white train conductor refused to give Reeves something to eat in spite of him having meal coupons. Reeves went to the military police, who told him to do what the white conductor said, or face being locked up on the train. Reeves was forced to pay for his meal because he could not go into the segregated dining car.

Experiences like those would fuel Reeves’ passion for Black journalism’s role in exposing racial injustices while advocating for the needs of disenfranchised people of color.

After completing his service in 1946, Reeves returned to The Miami Times. By then, Blacks could not sit at segregated diners downtown. Members of the Klu Klux Klan would often parade through Miami’s bustling downtown. Parks and schools did not accept Blacks either and living conditions among Blacks worsened as slums in Overtown increased.

Reeves joined Reverend Theodore Gibson, the president of the local NAACP Chapter and began leading protests for better conditions for Blacks in Miami. Out of 28 beaches, only Virginia Key Beach was open to Blacks. On November 7, 1957, Reeves led a group of seven Black leaders to Crandon Park, a segregated white beach near Miami. Reeves and the men earlier talked to several county commissioners, saying that as taxpayers they had the right to frequent Crandon Park or any segregated beach. Wearing their bathing suits under their clothes, Reeves and the men took off their slacks and went into the water while several police officers watched. Blacks began frequenting other white beaches after the incident.

Blacks were not allowed to play at city-owned golf-courses in the 1940s. But that changed when Reeves and Gibson filed a lawsuit that went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In a landmark case, Rice v. City of Miami, the Supreme Court ruled that the city could not continue accepting tax money to build and maintain golf courses while denying its use to all residents.

In an interview on the History Miami Museum website, Reeves recalled an experience he had when Dr. Martin Luther King came to Miami during the Civil Rights Movement.

“When Martin Luther King came down, I attended some of his meetings. My friend was a good friend of King’s and I used to attend meetings where he would preach to us about nonviolence. I remember talking to Martin a few times and I said, “Martin, you really believe that if I was somewhere and a white guy spat on my face, you think I would walk away from that? I said I’d try and kill that son of a b—-. He said, ‘That’s why you’ve got to try to learn to control yourself.’ I liked him.”

That was Reeves the activist.

Reeves, as the publisher of The Miami Times, was just as fierce. It was the only job Reeves would have throughout his life. He worked his way up the ranks as columnist, reporter, managing editor, and editor. When Reeves’ father died in 1970, Reeves became publisher.

By then The Miami Times had established itself as the Black newspaper of record.

During the 1960s The Miami Timesran a front-page story advocating for the termination of Miami Police Chief Walter Headly, whose Stop and Frisk policy of searching Blacks lit up racial tensions in the city. Headly was eventually fired and the Times readership grew.

When four Miami police officers were acquitted in May, 1980 of killing Arthur McDuffie, a Black salesman, Blacks took to the streets. White newspapers and local television stations described it as a riot. With Reeves at the helm, The Miami Times called the incident a “protest.” When another Miami police officer was acquitted in 1993 for killing two Black motorists in Overtown, The Miami Times called the civil unrest a rebellion.

There were other highlights under Reeves’ leadership at The Miami Times.

In 1985, Mayor Maurice Ferre lost the Black vote and was defeated in his re-election bid after The Miami Times ran a series of editorials criticizing the mayor for firing Howard Gary, Miami’s first Black city manager.

In 1993, Reeves and The Miami Times published editorials and stories supporting a boycott of Miami Beach hotels that cost the tourism industry millions of dollars.

Black leaders accused county leaders of snubbing Nelson Mandela after they withdrew plans to give him a proclamation and key to the city when the anti-apartheid leader publicly expressed his support for Cuban Dictator Fidel Castro.

The National Bar Association and ACLU were among many organizations that did not bring their conventions to Miami Beach in support of the boycott.

The boycott lasted three years and cost the tourism industry between $20 to $50 million. Mandela was given an official proclamation and the hotel industry implemented programs to boost Blacks in its facilities. Miami Beach got its first Black-owned luxury hotel, the Royal Palm Crowne Plaza.

“It was important that we had a communication outlet to get our message out,” said H.T. Smith, a prominent Miami attorney who spearheaded the boycott. “The mainstream media would not give us any coverage. The Miami Times was essential to the boycott’s success. The boycott would not have been successful without The Miami Times. And our friendship grew as a result of this partnership.”

Former Miami Times executive editor Mohamad Hamaludin, who worked for 15 years at the newspaper, said, “Reeves was a fine gentleman. By the time I got to The Miami Times, he and the staff had already established it as a voice for people who didn’t have a voice.”

Reeves was the first Black to serve on the boards of the Miami-Dade College, Barry University, the Greater Miami Chamber of Commerce, and the United Way of Dade County. He also served as organizing chairman of the board for National Industrial Bank, which was the first integrated bank in the State of Florida.

While serving on many of these boards, Reeves pushed them to hire more Blacks when they were reluctant to do so. As a board member of Miami-Dade College, Reeves threatened to lead a vote to stop doing business with the school’s law firm because it resisted his calls to hire Black attorneys in its offices.

Reeves assisted Crusader Publisher Dorothy R. Leavell in bringing the NNPA Annual Convention to Gary in 1983 after Black political power gained a foothold in the Steel City.

“He believed in the Black Press very deeply,” said Leavell who first met Reeves in 1962. “Whatever he did, he was always on the right side of the battle. He remained a forward thinker to the very end. He was truly one of the last of the great Black publishers from the old school in the Black Press.”

Today, The Miami Times is the oldest and largest Black newspaper in the Southeast. For the past two years it has been named Best Black Newspaper by the National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA), which represents over 200 Black newspapers across the country. In 2011, NNPA named Reeves Publisher of the Year. In 2017, Reeves was inducted into the National Association of Black Journalists Hall of Fame.

In 2017, Miami recognized Reeves with an honorary street sign at 6 Street and NW 2 Avenue near the Black Archives History and Research Foundation of South Florida where he was a board member.

Reeves was a life member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Sigma Pi Phi Fraternity, Inc., Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc., and a founding member of the Episcopal Church of the Incarnation in Miami, Florida.

He was awarded honorary doctorate degrees from the University of Miami, Barry University and Florida Memorial University.

For years, Reeves had provided scholarships to aspiring journalism students at his high school alma mater, Booker T. Washington.

Reeves served for 10 years as president of the Amalgamated Publishers Inc. in New York City, which represented over one hundred African American-owned newspapers throughout the United States. He was also elected to serve two terms as president of the National Newspaper Publishers Association.

He retired in 1994 and assumed the role of publisher emeritus but Reeves remained active as a prominent leader in the Black community.

Reeves outlived both of his children. In 1982, Reeves’ son, Garth C. Reeves, Jr., died of colon cancer when just 30 years old. This past September, Reeves’ daughter, Rachel died at 68. His grandson, Garth Basil Reeves now heads the family newspaper dynasty at just 29.

According to The Miami Times website, Reeves’ funeral will be at 10:30 a.m. Saturday, Dec. 7 at the Historic Saint Agnes’ Episcopal Church of Miami, 1750 NW Third Ave., Miami.

[ad_2]

Source link