[ad_1]

SAN FRANCISCO — It was three days after high school graduation when it happened. Nour Naas, then 18, stood in the alleyway outside her home and watched her father shoot seven bullets into her mother’s chest.

Naas, now 24, recalled that day between deep breaths, under a mask of stoicism, seemingly afraid that the earth underneath would crumble if she dared show any emotion. She sat up, poised and suddenly attentive to herself, as she ran her hands against the fabric of her denim dress and adjusted the cappuccino-colored hijab that framed her big brown eyes.

“I know that he knew he wanted to kill her,” said Naas. Only two weeks before the 2013 shooting, her father had sat Naas down and, out of the blue, asked her what she would do if her parents died. Naas didn’t know what to make of his question at the time.

But standing there in the alleyway watching her father commit the unthinkable, she understood. She screamed, unable to take her eyes off her mother’s body lying in a pool of her own blood on the ground.

Without looking back, she began to run.

I know that he knew he wanted to kill her.

Nour Naas, 24

It is a challenge for domestic violence victims to seek help, regardless of their ethnicity or religious background. Shame and fear are powerful silencers. But Muslim women like Naas’ mother face distinct and arduous obstacles, according to a HuffPost investigation. HuffPost spoke to more than a dozen survivors from Muslim backgrounds, as well as staffers from multiple faith-based agencies catering to the American Muslim community.

A number of victims said they were distrustful of U.S. state and federal agencies due to past experiences of discrimination. When they did decide to seek help, HuffPost found, they often contended with Islamophobic stereotypes, sometimes voiced by the very people tasked with keeping them safe. Many who turned to religious leaders for support said they encountered unprepared imams with little to no training on the dynamics of domestic abuse. Almost all of the women interviewed said they struggled with the cultural stigma of divorce.

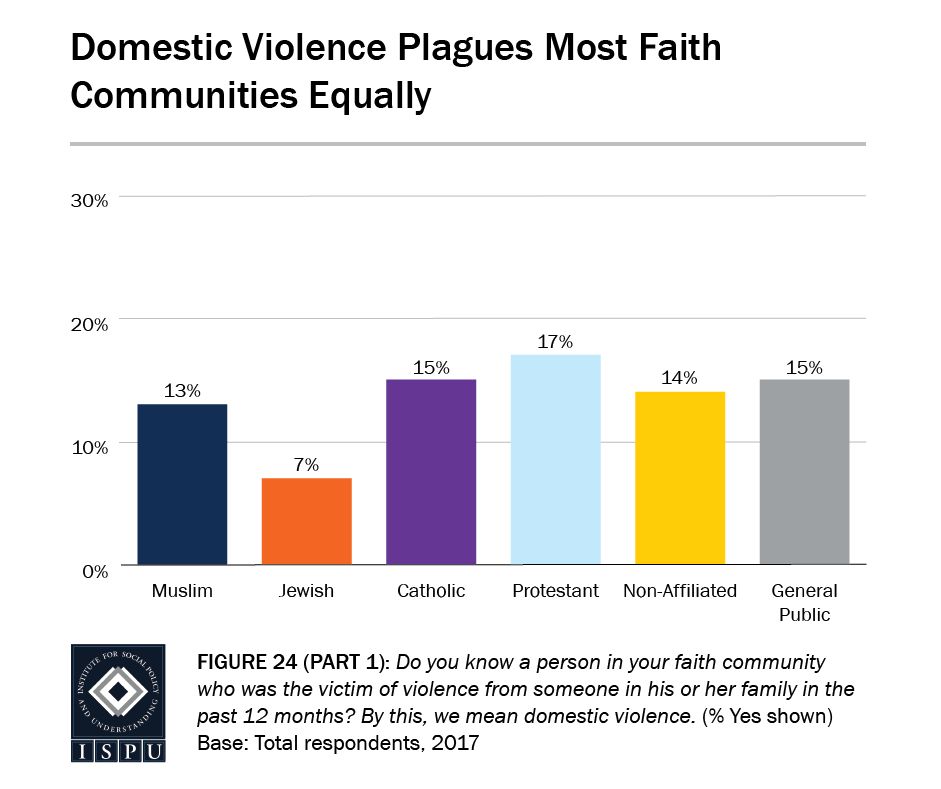

Domestic violence does not discriminate, and victims span all races, ages, ethnicities and religions. Around 1 in 4 women have been victims of severe domestic abuse, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There is scant data on the prevalence of domestic violence in the Muslim community, although a 2011 survey found that more than 66% of Muslims know a fellow Muslim who has been physically abused. Over 53% reported experiencing some form of abuse themselves. The research, collected by Peaceful Families Project (PFP) and Project Sakinah, two faith-based organizations, is the largest dataset on the topic, highlighting a dire need for more research.

All of the women interviewed by HuffPost, many who spoke anonymously, described a tumultuous journey for help.

Some were immigrants who spoke about the difficult choice of staying with an abuser because he was their legal sponsor or having to stay because they did not know enough English to safely find shelters.

Many were single mothers of children who also suffer from trauma and mental health issues due to either witnessing abuse or being abused themselves.

Nearly all of them agreed that this was not a religious issue — but described feeling intense shame after seeking help and a dire need for fellow Muslims and religious leaders to do more to tackle an issue that has plagued their community for too long.

Reliving A Nightmare

When police found Naas, she was lost and still running. After taking her in for questioning, she was later released to a family friend — the same person her father instructed her to contact in their earlier conversation about what she’d do if her parents died. That night, after he killed her mother, Naas’ father was killed in a subsequent shootout with police.

Naas and her three brothers have never discussed what happened to their mother. They grieve privately, in their own ways, she said.

One afternoon in October, sitting in a bright living room at the Arab Cultural Community Center in San Francisco, Naas recalled the first time she became aware of her father’s violence. It was a winter night in 2009. She watched him squeeze her mother tight and shake her body violently until her skin turned black and blue. He threw a wooden chair at her when she refused to comply with his order to sit down. Naas yelled for her brothers to come help. The four siblings wedged themselves between their parents and ended the fight.

“The way I saw my dad after that totally changed,” said Naas. That night, her mother filed a police report. When her father found out, he threatened to kill her if she ever contacted the police again. It wasn’t the physical violence that terrified Naas, it was the threats, the unpredictability of when and how her father might lash out.

The recent surge of Islamophobia — hate crimes, bigoted policies and daily incidents of harassment — has only made confronting domestic violence more challenging for the Muslim community. As stories in the media often stereotype Muslim men as a monolithic, violent group that oppresses women, fear of judgment from non-Muslims makes the issue of gender-based violence especially difficult to address, said Juliane Hammer, an associate professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the author of the book “Peaceful Families: American Muslim Efforts against Domestic Violence.”

“Anti-Muslim hostility produces an atmosphere where Muslim women — in addition to the abuse that they are recognizing and want to do something about — are also realizing that reporting or seeking help will reflect badly on men in their community but also on the community as a whole,” Hammer told HuffPost.

Anti-Muslim hostility produces an atmosphere where Muslim women … are also realizing that reporting or seeking help will reflect badly on men in their community but also on the community as a whole.

Juliane Hammer, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Since the election of Donald Trump, Hammer said policies like the Muslim ban and the crackdown on immigration have made navigating the legal system much more complicated and intimidating for Muslim women, sometimes preventing them from accessing social services.

“Muslim domestic violence survivors are perpetually re-victimized by these policies,” said Hammer.

Filing a restraining order or calling the police on your spouse can also be seen as bringing shame to the family. In Islam, the cohesion of family life is emphasized in both the faith and the culture, and divorce is frowned upon in conservative communities. Many Muslim women still struggle with the concept of “airing their dirty laundry,” and seeking help from professional networks is largely discouraged.

Muslim women eschew seeking help for fear of causing more harm than good, said Mouna Benmoussa, who heads the Arab Woman Services program, an extension of Asian Women’s Shelter in San Fransico. Muslim women fear their husbands will be deported or go to jail, she said. “Even with all of that abuse and ill-treatment, they do want their husbands to stay in the country.”

When Mainstream Agencies Perpetuate Hate

Naas spent years trying to understand why her father killed her mother. She thought volunteering for domestic violence agencies would help her learn about the cycle of abuse and why the violence is hard to stop. What she didn’t expect was the Islamophobia of advocates who were supposed to be helping.

In 2017, while volunteering at an agency in Oakland, Naas asked a staff member if the team had reached out to any mosques. Naas believed it was important to be in touch with members of the local Muslim community so they could benefit from domestic violence programs. “Are Muslim women even allowed to talk?” a staffer replied to Naas, dismissing her suggestion. In another incident, the same worker commented that a Muslim client who was suicidal reminded her of “ISIS suicide bombers.”

While domestic shelters are a crucial support system for victims fleeing abuse across the U.S., these safe spaces can sometimes become another source of abuse for Muslim women, as Naas observed. Experts interviewed by HuffPost said domestic violence advocates told Muslim women that their abuse was expected. Those advocates falsely believed it was built into the Islamic faith.

In Baltimore, the Muslimat Al-Nissa shelter exclusively caters to Muslim survivors who don’t feel safe going anywhere else. The shelter’s founder, 65-year-old Asmaa Hanif, told HuffPost it was imperative to provide a space that accommodates Muslim women in every way, including by providing them with a place to pray and halal food to eat.

“What we find is that when you put Muslim women in a shelter with others, even if the shelters say that they are Muslim-friendly, you run the risk of people mistreating these Muslim women. You cannot control the mindset or the actions of individuals there,” Hanif said.

Hanif, who has been running the shelter for over 40 years and resides in the house herself, said her clients told her of instances in which shelter cooks put pork in Muslim women’s meals (many observant Muslims don’t consume pork), or shelter residents harassed Muslim women while they attempted to pray. This type of discrimination has only increased since Trump’s election, Hanif said, driving more women in the Baltimore region to her house.

Naas believed it was important to be in touch with members of the local Muslim community so they could benefit from domestic violence programs. ‘Are Muslim women even allowed to talk?’ a staffer replied.

There are thousands of domestic violence agencies — shelters, counseling agencies or advocacy groups — that offer resources to the estimated 10 million victims of domestic violence in the U.S. every year. Domestic violence hotlines receive over 20,000 calls nationwide on a typical day, according to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence.

However, with an increasing volume of victims, agencies across the country are operating with less funding and fewer staff and resources. According to the National Network to End Domestic Violence (NNEDV), nearly 80% of states reported cuts or reduction in programming funds as the demand for services is only increasing.

“I wish that every single frontline advocate across the nation and all the 2,000 local programs had the benefit and requirement of countless hours of implicit bias training and inclusive and cultural competency work. But unfortunately, not everybody is able to get that training,” said Cindy Southworth, NNEDV’s executive vice president, told HuffPost. “We want to see every local program that is a warm and welcoming place for Muslim women and all survivors.”

Understanding The Role Of Faith

It is not known if Naas’ mother ever talked to a domestic violence advocate or sought help from a shelter. But she did turn to her local imam for support.

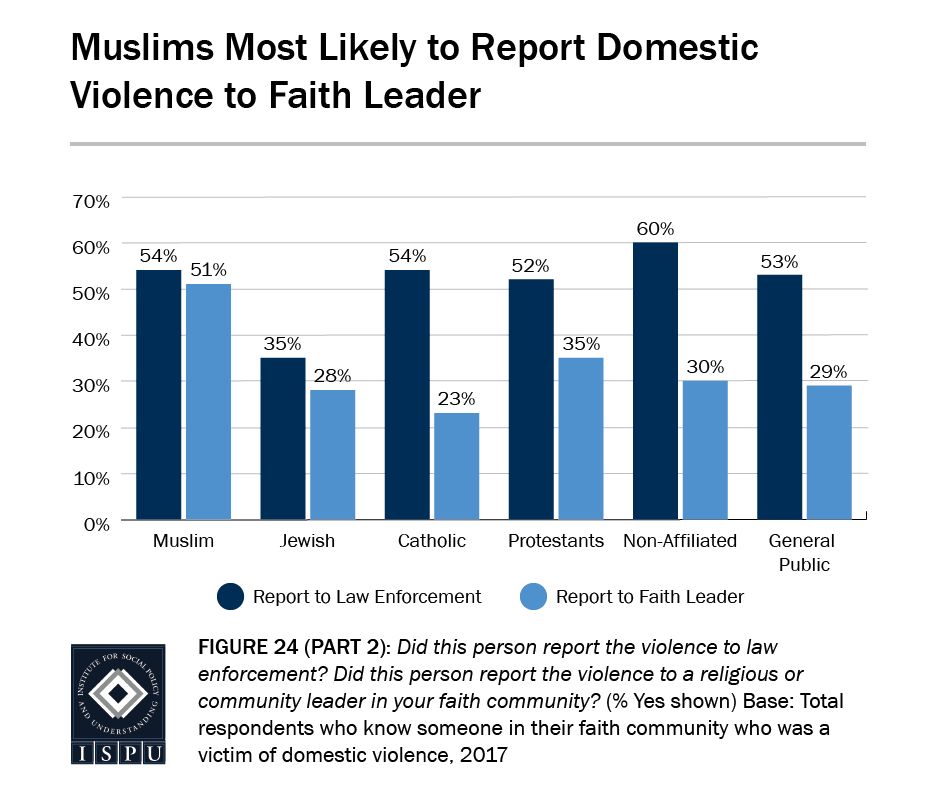

Imams, much like priests, offer congregants guidance on a range of matters beyond the religious realm. It’s not uncommon for Muslims to discuss financial challenges and family issues with their imam, including domestic abuse. In fact, compared to other faith groups, Muslims are more likely to report abuse to their local clergy, leaning on them right after friends and family.

But not all imams ― whose education is generally centered on Islamic scripture and interpretation ― are trained to work with victims of abuse.

“When an imam is hired, they’re not told in their job description that they’re going to be providing counseling for serious cases, or that they are going to be encountering domestic violence,” said Salma Abugideri, a licensed counselor and the director of training at PFP, a national domestic violence organization that focuses on the Muslim community in the U.S. “They’re not prepared, but they don’t know they need to be prepared.”

Abugideri’s organization, founded in 2000, trains religious leaders on the dynamics of domestic abuse and leads workshops across the country. In the past few years, demand for PFP’s training has been on the rise, she said.

“To me, [this] reflects their awareness that they are not trained properly, that they’re not really equipped to handle the domestic violence piece or even the counseling piece,” she said.

Khalid Latif, the executive director and chaplain for the Islamic Center at New York University, said that hundreds of women, from teenagers to elderly women in their 70s, have disclosed abuse to him over his 14-year tenure.

Latif said the problem isn’t Islam as a faith, since Islam prohibits violence and poor treatment of women, but the need for faith leaders to get training and form partnerships with Muslim-run domestic violence agencies.

“The traditional curriculum and pedagogy, in most Muslim institutions of religious learning, is fundamentally rooted in the kind of rote memorization of certain books and texts, and there’s nothing wrong with that,” said Latif. But the 37-year-old imam added that providing social services and doing fieldwork is also an obligation for religious leaders for the congregation they are leading.

Religious leaders are hesitant to address the issue for fear of adding to the rising Islamophobia already out in the world, said Mona Kafeel at the Texas Muslim Woman’s Foundation in Dallas. Her organization has served more than 3,000 survivors of domestic violence over the past five years and takes over 1,000 calls daily through its 24-hour crisis hotline. Kafeel said many Muslim leaders also feel shame when it comes to acknowledging domestic violence in their communities and airing the dirty laundry of Muslim Americans.

Some survivors told HuffPost that their abusers cherry-picked lines of Islamic text to try to justify their actions and guilt their victims into staying in an abusive relationship.

That’s a common tactic for religious abusers of any faith that makes it even harder for women to justify leaving, Latif said.

“The minute you have to start utilizing verses from the Quran to somehow justify like, your right to exist in tranquility or without oppression, it becomes problematic,” he added.

Despite the challenges, however, many survivors told HuffPost that their faith is also what gave them the strength they needed to seek help.

Fighting The Stigma

It has been six years since Naas’ mother’s death. While Naas continues to speak out about domestic violence, she often finds herself frustrated with her local Muslim community for referring to her mother’s killing as a homicide and not calling it what it is — domestic violence that developed for years before resulting in a premeditated murder. Others have urged Naas to stop writing about the topic of gender-based violence and to just “move on.”

But Naas can’t. These days, she works at the Asian Women’s Shelter between her class schedule at California State University, East Bay, where she is majoring in sociology. The agency caters to immigrant and refugee survivors of domestic violence, and Naas has worked there for over a year.

On a damp morning in October, Naas joined a group of Arab Muslim women who met over coffee and tea at a local community center. They piled into a bright room where portraits of strong Arab women in history hung on the walls. All of the women were survivors, but many of them were meeting for the first time.

The women swooned over a baby whose mother had fled her home to a nearby church and then eventually reached the Asian Women’s Shelter. All of the women spoke anonymously, highlighting the intense fear and stigma they were still fighting. One woman spoke about the language barrier she faced and the humiliation she felt whenever she spoke in U.S. courts. Another woman discussed the need to recognize the insidiousness of emotional abuse.

“I wish he would just hit me,” said one woman quietly. The other women nodded in agreement. The emotional scars were harder to heal.

The obstacles the women faced were the same: securing housing in one of the most expensive cities in the country, navigating the U.S. legal system, and wanting to leave — but not to punish — their abusers.

Sometimes, Naas said, she feels grateful that the police killed her father so she doesn’t have to navigate any sort of relationship with him. But his death didn’t provide any closure. So she writes, even when others tell her to stop, hoping to find closure and meaning through her work. She thinks about her mom every day.

“In my heart, there’s no doubt that my mom would be proud of me,” she said. “I just want to honor my mom.”

Are you a Muslim woman with a story you want to share? Send an email to rowaida.abdelaziz@huffpost.com.

Need help? In the U.S., call 1-800-799-SAFE (7233) for the National Domestic Violence Hotline.

REAL LIFE. REAL NEWS. REAL VOICES.

Help us tell more of the stories that matter from voices that too often remain unheard.

[ad_2]

Source link