[ad_1]

Emma Amos (born 1938) is a postmodernist African-American painter and printmaker.

Early life

Emma Amos was born in Atlanta, Georgia on March 16, 1938. Amos took an interest in art at an early age, creating “masses of paper dolls” and learning figure drawing from issues of Esquire and the art of Alberto Vargas, and was painting the figure by the age of nine. Her mother had aspirations of Amos studying with Hale Woodruff, but he did not accept many private students and left the area before she had the opportunity to study with him.

At eleven, Amos took a course at Morris Brown College, where she worked on her draftsmanship and took note of the work that African American college students were producing at the time. By high school, Amos was submitting her work to Atlanta University art shows. She graduated from Booker T. Washington High School in Atlanta at the age of 16, and applied to Antioch College, because of their progressive policies.[1]

Education

Amos studied at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio,[2] at the London Central School of Art in England, and at New York University.[3] While at Antioch, Amos worked for half of the year, and studied for the remainder. She worked in Chicago, New York, and in Washington, which enabled her to visit galleries and museums, which had been less accessible in Atlanta. Her fourth year at Antioch, she went to England and studied at the London Central School of Art, where she learned to print and etch under Anthony Harrison, and began to paint with oils, which she had not done before.[4] Amos received her degree from Antioch in 1958, then went back to London for her degree in etching, which she received in 1959 after two years of study.[4]

Career

Emma Amos moved to New York City after feeling stunted by the slow move of the Atlanta art scene. Amos was not expecting the level of racism, sexism, and ageism that she encountered upon moving to New York. Galleries would not accept her under the premise that she was too young to show, and studio teaching jobs rejected her on the grounds that only mature artists could teach.[5] Amos was told by both Cooper Union and the Art Students League that they were not hiring after she applied for a teaching position.[6] The difficulty of entering work into galleries led her to teach as an assistant at the Dalton School where she met artists and was introduced to the New York and Easthampton art scene, where she experienced difficulty showing her work in a “man’s scene.” It was also around this time that Emma Amos began her career as a textile designer, working for the weaver and colorist Dorothy Liebes, where her designs were translated into unique carpets.

In New York, Amos joined the printmaking studios of Letterio Calapai (a part of Stanley William Hayter’s Paris Atelier 17) and Robert Blackburn’s Printmaking Workshop.[6] Despite the difficulty African Americans face in entering the art scene, as there is often a lack of access to dealers and curators, Amos persevered and received her M.A. from New York University in 1965. While at NYU, she became reacquainted with Hale Woodruff, who was a professor there at the time.

At the age of 23, Amos had a meeting with Woodruff for a critique of her prints, and he told her about Spiral. The group was a collective of African American artists, founded in 1963 by Romare Bearden, Charles Alston, Norman Lewis, and Hale Woodruff. The group was interested in discussions of Négritude, a philosophy born out of opposition to French colonialism and centered around encouraging a common racial identity for black Africans around the world. Spiral was formed out of the Works Progress Administration and the Harlem Renaissance. Woodruff took some of her work to one of their meetings at their rented storefront, and the members of the group liked her work enough to invite her to join as their first and only female member.[7] Amos thought it strange that no other women artists were asked to join the group, even though they were acquainted with the members of Spiral.

Amos felt that joining Spiral would be useful because she did not know many artists in New York at the time. Amos worked full-time as a designer during the day, and studied full-time in the evenings, and made time to paint on the weekends. In May 1965, Spiral rented a gallery space at 147 Christopher Street, where they had their first and only exhibit. Amos was represented by a (now lost) etching—Without a Feather Boa– ” a nude portrait bust of the artist staring indifferently at the viewer from behind a pair of dark sunglasses.” Prior to Spiral, Amos was resistant towards the idea of “black art” and galleries that only showed work by African Americans, but she came to understand that these were often the only options available to black artists at the time, and also learned how to integrate race and gender politics into her work without her work becoming dominated by the process of political engagement.

Spiral stopped meeting shortly after 1965, when rising rent prices lost them their gallery and meeting space in the Lower East Side. During the 1970s, Amos went on to teach textile design at the Newark School of Fine and Industrial Arts, weaving on her own looms at Threadbare, a yarn and weaving shop on Bleeker Street and thrived as a weaver due to the propagation of weaving and fabric art within the Feminist Art Movement.[6]

Amos originated and co-hosted Show of Hands, a crafts show for WGBH-TV in Boston in 1977-79, and later became a Professor at the Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University.[8]

Style

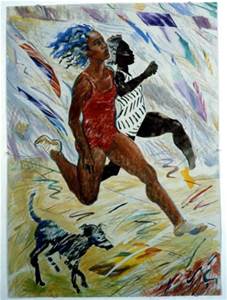

Amos combines printmaking, painting and textile in her self-referential works, usually on linen, large scale, and unframed. She uses acrylic paint, etching, silkscreen, collagraph, photo transfer effects with iron-on fabric, and African textiles. She borrows schema, subject matter and symbols from European art while pictorially quoting artists like Paul Gauguin, Malcolm Morley, Lucian Freud, and Henri Matisse. Amos demonstrates the deconstructive license of postmodernist works in her use of applications from several disciplines on the same picture plane, making a “seamless work of art”.[8]

As well as bordering her paintings with African fabric, Amos sews, appliques, embroiders and occasionally quilts with her own weavings, Kente cloth and batiks. The scale and textural layering of the work resembles forms often found in European prestige tapestries and the African diaspora.[8]

Art museum director, Sharon Patton, summarizes her oeuvre thus:

[Amos’s] sequence of paintings is anecdotal, but the objective of each is the same: to argue constructively against norms in the field of art as well as society. Her responses are reactive and reflexive; she ably uses her paintings as a means to analyze and assess cultural production, authorship, meaning and consumption. Amos is quintessentially postmodern because she questions the validity of canonical traditions and institutions that for so long have been biased against the inclusion of women and artists of color, especially blacks.[8]

Among the variety of mixed media that Amos uses in her work, the main subject is often figurative. Unlike many figurative artists Amos does not like to paint the nude figure. She likes painting clothed figures because she believes that painting the nude figure is sexist, and that clothing shows culture.[7]

During her time at Central School of Art, Amos studied abstract painting, and produced some Abstract Expressionist work for a period of time. After a while she deemed abstraction too easy and arbitrary, so she returned to painting the figure because it was more challenging. This influence is still present in her figurative work.[7]

Amos uses her art to explore themes of race and gender, contending that the very act of being black while an artist is political in nature. She cites well-known White, male artists, such as Picasso and Gauguin, who were praised for including subjects of color into their work, while African American artists were seemingly expected to paint other subjects of color. Amos incorporated white subjects into her art, particularly images of the Ku Klux Klan, challenging this assumption.

Feminism

Amos admits that being from the South, as an African woman, she has always been aware of the adversities she faces in her everyday life. However, in relation to Feminism, Amos did not become actively involved until the late 1980s.[7] Before this time, in the early 1970s, while raising children, Amos was invited to join a Feminist Group of artists that met in New York City parks. When choosing whether or not to attend, Amos stated, “From what I heard of feminist discussions in the park, the experiences of black women of any class were left out. I came from a line of working women who were not only mothers, but breadwinners, cultured, educated, and who had been treated as equals by their black husbands. I felt I could not afford to spend precious time away from studio and family to listen to stories so far removed from my own.[4]”

It was not until the late 1980s, when she began teaching at Mason Gross, a school a part of Rutgers University, that she decided to participate in the feminist group Heresies. Within this group, women worked together, from all backgrounds, to publish pieces of artwork and writing of unknown women artists, published in a series of magazines and discussions. When speaking on the group, she declared, “And that’s what Heresies became for me. All of my disdain for white feminists disappeared, because we were all in the same boat. We just came to the boat from different spaces.[10]” For numerous years, Amos also attended meetings with the group, Fantastic Women in the Arts. This group, also explored the artwork and writings of many female artists, but also focused on how the revolution in the 1960s and 1970s, concerning education on racism and sexism, failed to actually make any difference for black Americans or women. It is in this group that Amos discussed the privilege of white Americans, and how that was evident in the arts in everyday life.[4] Amos stays active in her involvement in these issues and providing education to younger generations, however, keeping groups going seems to be the hardest challenge.[4] Amos feels that “artists who are not white, young, and straight, and who are openly political, and feminist, seem to still be on the margins. [She] hope[s] we all will see more change soon.[4]

[ad_2]

Source link