[ad_1]

Rembrandt’s The Night Watch (1642) being studied as part of “Operation Night Watch” at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

COURTESY RIJKSMUSEUM

I think too much exposure to contemporary art has damaged my brain. A recent event offered decisive proof. During a viewing of “Operation Nightwatch” at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam—a nine-month project dedicated to the study and restoration of Rembrandt’s monumental 1642 painting The Night Watch—I had the pleasure of watching as the work was slowly scanned by a large machine while suspended in a glass room. Looking at museum-goers view the partially obscured masterpiece, I couldn’t help but see the process as a kind of conceptual art, perhaps a piece by someone like Mark Leckey, in which art historical signifiers were brushing up against contemporary technology, all wrapped up in an ultra-clean cube.

But clearly that wasn’t the intention. In reality, “Operation Nightwatch” is an in-depth initiative dedicated to preserving and shedding new insight on Holland’s most famous painting.

“I mean, it’s a 350-year-old painting, so you really have to be conscious about its condition,” Pieter Roelofs, the head of paintings and sculpture the museum, told me that day, discussing the origins of the efforts. He was wearing a crisp blue suit. It was a rainy Monday. Roelofs said that the institution is constantly monitoring its collection, and when they noticed “something going on” with The Night Watch, they decided a full examination and conservation project was in order.

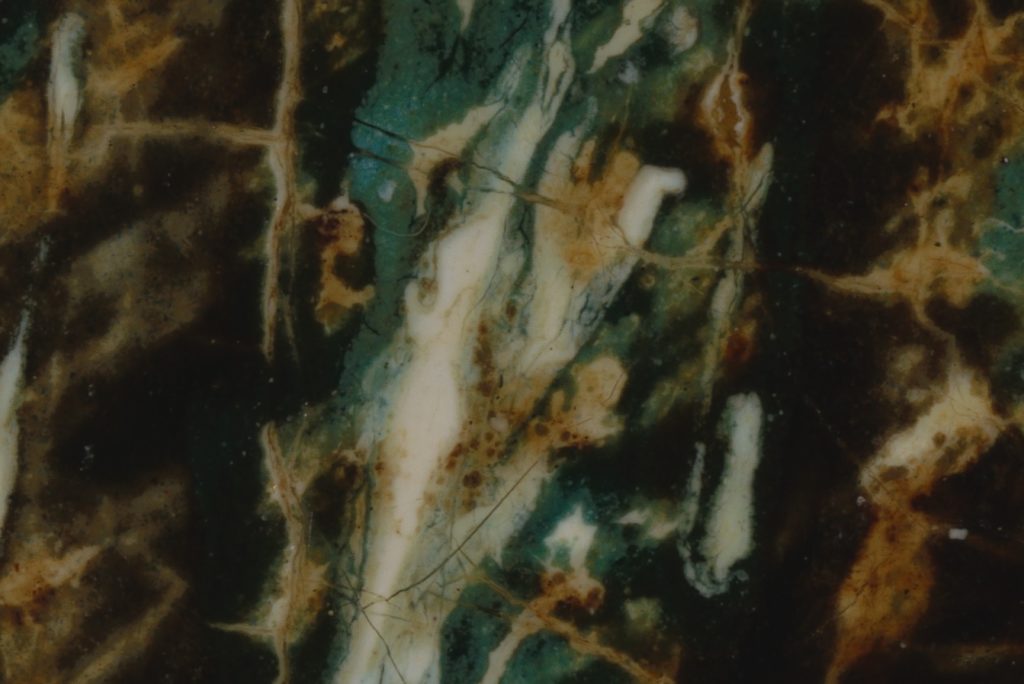

A detail of The Night Watch, zoomed in to 5340 dpi, resolution 4.75 micrometer.

COURTESY RIJKSMUSEUM

With “such an important painting—I mean, it’s one of the top paintings in the world—we didn’t want to do this outside of the public eye,” he said, noting that, for the museum’s global audience, a chance to see the work is a major reason to visit the institution. “Just once in your lifetime you really need to have the opportunity to see the painting,” he continued, “and by doing this examination project we really believe that we are adding value to the venue and value to the experience itself as well.”

The process started in July, with the move of the painting into the glass chamber where it now resides. Currently, scanning is underway—the museum is using a technology called macro X-ray fluorescence scanning, an absurdly hi-def procedure that can map out the chemical elements embedded in the paint. In the process, it might even uncover new truths about the artist’s compositional methodology. The museum will then assess the current condition of the painting. After that, a conservation plan will be adopted and followed.

“By identifying the individual element, you’re able to identify the pigment as well, and that’s helping us to understand the buildup of the painting as well, and how Rembrandt altered himself and corrected himself,” Roelofs said, of the scanning process. “So, he kept working on this, almost struggling on his compositions, and that’s interesting as well. I mean, we tend to present him as a kind of genius, but he was really hard-working.”

Rembrandt’s The Night Watch (1642) in all its glory.

COURTESY RIJKSMUSEUM

All of that said, Roelofs did offer to meet me halfway when I gave him my take on the contemporary art-like optics of the whole affair. “What we are doing is at the highest quality possible, and I think great art is always at the highest quality as well, so I do understand why you would think about that,” he said. I assumed the employees have not been thinking of themselves as performance artists. “They are not. No,” Roelofs responded. “I hope they’re not.”

The Night Watch, a groundbreaking group portrait of Dutch civic officers lauded both for its sprawling scale and virtuoso display of light and motion, means a lot to citizens of the Netherlands. It has been through a lot. In 1715, when the painting was moved from its original location at the Kloveniersdoelen (“musketeers’ shooting range”) in Amsterdam to City Hall, it was trimmed at the sides so it could fit through gateways. Flashing forward to 1911, an unemployed shoemaker punctured the work with a knife in protest of his joblessness. Then, in 1975, the piece was slashed by another knife-wielding man who told onlookers that he was doing it for the Lord. “It’s such an important painting that it attracts people from all—well, with all different ideas,” Roelofs said.

Different takes on the painting are crucial to the Dutch artist Rineke Dijkstra’s 2019 three-channel video installation Night Watching, which serves as a supplement to the main exhibition and is on view in the museum’s Gallery of Honour, on the same floor as the painting. Shot over six evenings, it shows 14 groups of people looking at The Night Watch and giving their own take on what they think the work means in the context of both history and their own personal experience. The painting is always out of the frame. In the piece, a group of Japanese businessmen comment that in their home country, branding tie-ins would be more thoroughly exploited (“They would sell Night Watch cakes,” one says). An old women in pearls states that “these men are here to have fun,” referring to the active militia group. Another person thinks that Captain Banning Cocq, who commissioned the piece, “comes off as an arrogant prick.”

Behind glass, the work continues.

COURTESY RIJKSMUSEUM

As for the audience in the building that day, the project-in-progress seemed to be a bit confusing to some. It wasn’t exactly like watching paint dry, but it was like watching paint get scanned. “I don’t know what’s going on,” I overheard one person say in an accent I couldn’t place. I talked to a metalhead in town with his sister from the East Coast of the United States. He was wearing a shirt by the American metal band Exmortus—who, curiously enough, mostly write songs about battle and war—and was in Amsterdam to catch a rare show by a Dutch progressive rock band. “It’s kind of disappointing that we can’t see [the painting],” his sister said. (The scanner was blocking uninterrupted views.) I heard another American, this one with grey hair, inquire to a guard about the process. She was told that there were many months left to go before the work would be completed. “Well, I’ll have to come back,” she said.

[ad_2]

Source link