[ad_1]

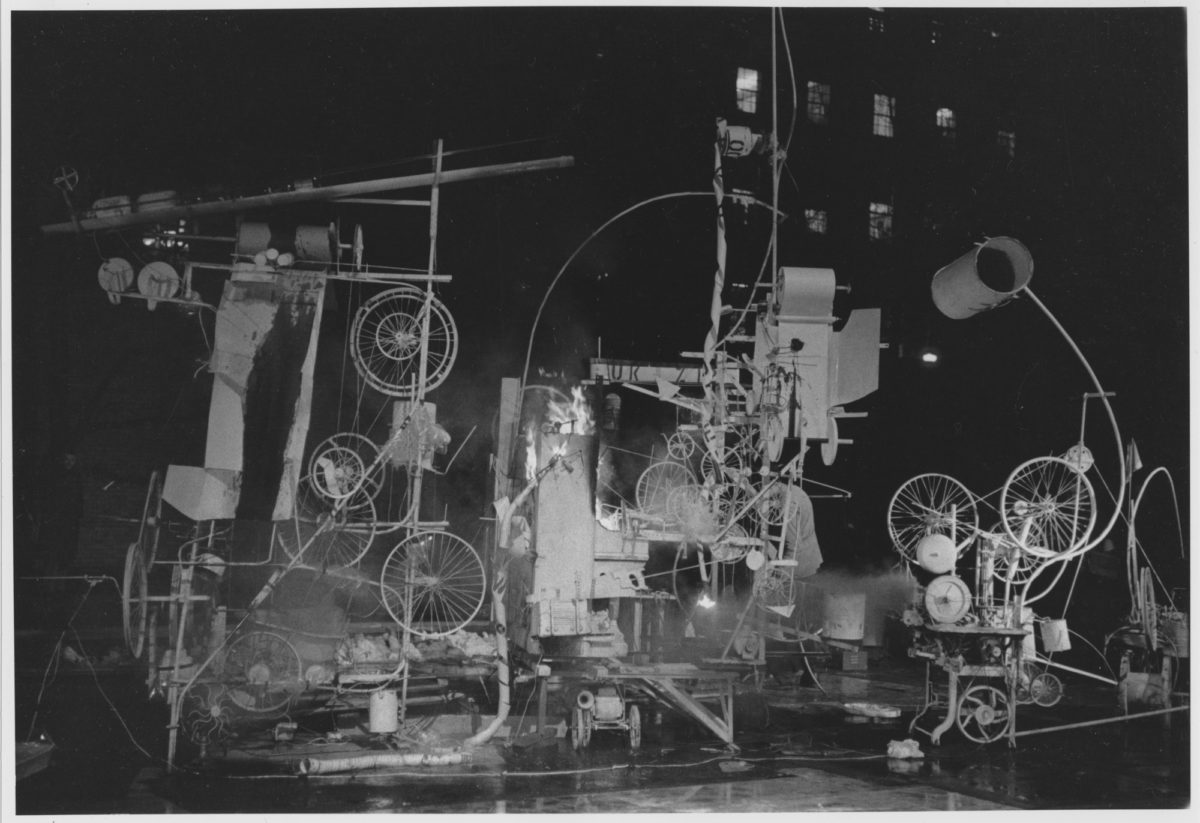

Installation view of “Homage to New York: A Self-Constructing and Self-Destroying Work of Art Conceived and Built by Jean Tinguely,” 1960, at Museum of Modern Art, New York.

COURTESY MUSEUM OF MODERN ART

The Museum of Modern Art in New York will reopen after a $450 million renovation and expansion on October 21, marking one of the most dramatic transformations in the institution’s long and storied history. In the run-up to the museum’s next incarnation, ARTnews looks back to important exhibitions from MoMA’s past and offers excerpts from articles and reviews from our archives—moving decade by decade from the museum’s inauguration to the present day. The fourth edition in this series features nine shows from the 1960s at MoMA, including a one-night-only self-destructing Jean Tinguely sculpture and the first major solo Pop show at the institution.

“Homage to New York: A Self-Constructing and Self-Destroying Work of Art Conceived and Built by Jean Tinguely”

March 17, 1960

The show: When MoMA curator Peter Selz learned that Jean Tinguely wanted to create a sculpture that would destroy itself, he immediately reached out—but came upon opposition from inside. “The museum was very uncomfortable and kept saying no, which may have been the correct attitude for the collections manager,” Selz told the Brooklyn Rail in 2011, “but I was the curator of painting and sculpture and I thought it was a good idea.” It turned out he was right, as Homage to New York (1960)—a rickety machine crafted from bicycle wheels, drums, a bathtub, and more—has come to be seen as one of the defining works of kinetic art. When it was shown at MoMA, on a rainy day, the work began emitting smoke, and the fire department had to be called.

What ARTnews said: “If it had not been for the rain, the event could be called ‘Black-tie Dada.’ Alfred Leslie, in a tuxedo, took some movies of the important and/or colorful members of the damp crowd that waited patiently for over an hour before the machines could be started. A cloud of smoke at one point blanketed the corps of free-lance and press-photographers, for a few minutes almost spoiling the reason for the whole party. But they managed to escape, and many photographs which might be published were taken. … In its sad and silly way, it was probably the most characteristic exhibition the Museum of Modern Art has had in years.” —Thomas B. Hess

Mark Rothko

January 18, 1961–March 12, 1961

The show: This major exhibition surveyed an Abstract-Expressionist giant’s career, from his early watercolors to a set of murals that were debuted as part of the show. Such a significant assemblage of Rothko’s work had never before been mounted before, and critics responded enthusiastically.

What ARTnews said: “Mark Rothko’s retrospective is one of the most beautiful shows ever presented by the museum. In a sense, the exhibition is a work of art: Rothko took a firm hand in both its selection and installation, constructing an arbitrary self-portrait with paintings dating from the past fifteen years. … This is, perhaps, the ideal kind of retrospective. The artist seems neither memorialized or classicized, but very much a person and very much at work.” —Thomas B. Hess

Installation view of “Rodin,” 1963, at Museum of Modern Art, New York.

COURTESY MUSEUM OF MODERN ART

“Rodin”

May 1, 1963–September 8, 1963

The show: For the biggest Auguste Rodin survey yet staged at a U.S. museum, MoMA secured some of the best works by the French sculptor in American collections, including a cast of the famed Burghers of Calais monument from the Rodin Museum in Philadelphia. Also included was what has since been one of the most iconic works in MoMA’s sculpture garden: Monument to Balzac, which was acquired in 1955.

What ARTnews said: “Rodin trusted the great traditional ‘subjects,’ the noble categories and ‘missions’ of High Art. A man of the people, he never questioned the popular belief in the artist’s responsibility to history nor his rather naive faith in messages. … A passionate modeler, Rodin discovered in the human figure the prototype of the autonomous solid, the fulfilled object, whose skin reflects light as steadily as the heart beats.” —P. M. Grand

Hans Hofmann

September 11, 1963–December 1, 1963

The show: Hans Hofmann—a mentor to many of the Abstract Expressionists as well as a new generation of American artists—was billed in a press release for this survey as “probably the most influential art teacher of the 20th century.” The show, which later toured Latin America and Europe, was regarded by critics as long-overdue.

What ARTnews said: “It would be fitting with the showing of forty paintings of Hans Hofmann, chosen for quality rather than to demonstrate his development, that the Museum of Modern Art would drop its role as keeper of the keys of modern art history; no position is more frivolous than that of esthetic Couéism or more false to the creation of art. … It is particularly fitting that the Museum should end its series of carefully documented and often lifeless presentations of modern artists and start a new tack with Hofmann, since his work just doesn’t develop along the mechanical lines of approved biographies.” —Fritz Bultman

“The Responsive Eye”

February 23, 1965–April 25, 1925

The show: This William C. Seitz–curated show saw MoMA moving away from Abstract Expressionism toward new styles, with a focus on what would now be termed Op and kinetic art. Because the work was so far from the Abstract Expressionism that had come to be expected, critics perplexed by the new kind of art—which confuses perception through illusions of motion and painterly or sculptural effects—bashed the show. The scorn grew so intense that one of the participants, Bridget Riley, even took a stand in ARTnews, calling out critics for their misunderstandings. (Also included in the show were Carlos Cruz-Diez, Gego, Robert Irwin, Heinz Mack, Agnes Martin, François Morellet, Julian Stanczak, and Frank Stella.)

What ARTnews said: “The Museum show itself, despite Mr. Seitz’s evident scholarship and good intentions, is a mishmash which suffers from acute Exhibitionemia (a chronic international disease). It lumps together at least six totally different kinds of painting and sculpture, including: the mystical; belated hedonist Geometries; various continuations of New York and Paris abstract styles; revivals of Bauhaus and Constructivist ideas; purist paintings related to the works of Newman, Rothko and Gottlieb (none of whom, quite rightly, are in the exhibition); eccentric and/or hermetic deviations (one critic, a devout New Yorker, said, ‘Op is Out-of-Town Art’; he is right; Op is pursued as fanatically in South Dakota as in the South of France); and, finally, the exhibition presents a large group of works which might be called Hard-Core Op—shapes that provoke strong, often violent, ‘retinal’ illusions, such as after-images, sensations of motion, of blinking, pinging, popping, glowing.” —Thomas B. Hess

Installation view of “The Responsive Eye,” 1965, at Museum of Modern Art, New York.

COURTESY MUSEUM OF MODERN ART

Jackson Pollock

April 5, 1967–June 4, 1967

The show: Though MoMA had already surveyed Jackson Pollock, this show was a milestone because of its size—with 80 paintings and 90 drawings and prints. But critics greeted it somewhat ruefully, viewing it as a turning point in the discourse surrounding Abstract Expressionism as a movement then becoming a thing of the past.

What ARTnews said: “A big exhibition of his pictures opens at the Museum of Modern Art, a space of words is appearing about him, and yet, surrounded by all this attention from curators, critics, and scholars, the Pollock we knew seems in danger of disappearing from sight altogether, turning into a monument, or a label, or a pelt nailed to a wall, or a feather in somebody’s cap.” —Thomas B. Hess

“The Art of the Real”

July 3, 1968–September 8, 1968

The show: While MoMA had been quick to take note of Abstract Expressionism, it was slower with ’60s-era movements like Pop and Minimalism. It took a visiting curator—E. C. Goossen, the chairman of the art department at Hunter College in New York—to right that oversight. In a press release for this group show, the museum said it wanted to explore “a significant identifiable change: the development in abstract art that is maximal in color and minimal in form and an unprecedented interaction between painting and sculpture” through works by Tony Smith, Donald Judd, Frank Stella, and others.

What ARTnews said: “Showing for the most part very uninteresting-looking squares and stripes and blobs of real liquitex paint, many of them by Ellsworth Kelly and a tiny selection of constructions such as those by Carl Andre and Tony Smith, the Modern showed that there are not too many different ways to do art now that will get noticed by such influential men as Goossen.” —Frederick C. Castle

Installation view of “The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age,” 1968–69, at Museum of Modern Art, New York.

COURTESY MUSEUM OF MODERN ART

“The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age”

November 27, 1968–February 9, 1969

The show: Pontus Hultén, the famed director of the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, sought to portray the many ways in which machines fascinated modern artists with this 200-work survey. But Hultén saw the show as something of an end of an era, in a post–atomic bomb time when people were less impressed by—and somewhat scared of—machines. And certain events surrounding the show brought it to the attention of the larger public: Midway through, Takis, who said he had not been consulted by MoMA about his work’s inclusion in the exhibition, took his work off view, put it in the sculpture garden, and led a protest. (The museum later agreed to take his work out of the show.)

What ARTnews said: “The Museum of Modern Art usually seems to take the same pieces out of the storeroom, place them a little differently and give the show a new name. But is this fair? A car by Bugatti. A model of a Tatlin machine. What’s to blame? They have plenty of machines? History. … In this show a machine is a car or a camera. What kind of machine is a camera? An Art Machine. You feed it Life and it turns out Art.” —David Antin

Claes Oldenburg

September 23, 1969–November 23, 1969

The show: The first Pop artist to receive a MoMA survey was Claes Oldenburg, who showed 200 works including The Store (1961)—a famed work that mirrored the look of window displays—as well as some of his soft sculptures.

What ARTnews said: “After a decade of public activity, Claes Oldenburg remains very much an isolated figure. Lack of definition in this instance clearly has very little to do with lack of attention; as much has been said and written about Oldenburg’s work as about that of his contemporaries. One of the few things that can be asserted with reasonable certainty is that he is so complex and varied that we cannot suppose that we have ever glimpsed the whole of his personality—hence any attempt at definition remains futile. … It is agreeable to realize that the present Oldenburg retrospective is very much a mid-career show. There is no reason to suppose that the texture of Oldenburg’s art will not become still richer.” —Christopher Finch

[ad_2]

Source link