[ad_1]

The year is 1998. The president is denying having sexual relations with a White House intern, an abortion clinic in Alabama is bombed by the same guy who bombed the Atlanta Olympics, and it’s still illegal for gay people to get married.

I’m seven years old and listening to the radio in my church parking lot, and my young life and mindset are about to change forever.

I grew up as a church kid. And that means more than just a kid who goes to church on Sundays. I was a kid who lived in church, who went to church a minimum of five days a week. I went to Sunday school, Tuesday Bible study, Wednesday prayer meetings, Friday praise dance practice and Saturday choir practice. I did my homework in pews. I attended vacation Bible school during the summer months and I went to conventions and Bible competitions during the school year. I sang, I danced, I preached, I worked. Church was my entertainment, my education, my everything.

“For the first time, being a church kid didn’t feel so weird and alienating thanks to Kirk Franklin’s innovation.”

And being a church kid came with certain rules and expectations of my behavior while I was in the sanctuary. No running, no yelling, no cursing, no kissing, no dancing, essentially no fun for me or the other kids who were in church daily. Sometimes, however, the grown ups would let us sit outside and listen to music in one of our parents’ cars, so long as we only played gospel music. Anytime we would try to sneak and play some TLC or whatever was on the contemporary radio stations, some church elder would come shuffling out of the church yelling at us to “turn that trash off.”

So imagine my surprise when, one day, while sitting in that parking lot with my friends doing what kids do ― disobeying the rules and quietly listening to the local hip-hop station ― we heard something that would blow our little minds and that would change my perspective on gospel and faith and Christianity for the rest of my life.

There was a beat drop. I heard a familiar voice recite the Bible book of Revelation, chapter seven, verses 16 and 17. The beat picked up. There was a choir but they were rapping instead of singing. And we were actually dancing; we couldn’t help it, the rhythm was so good. It was a gospel song! And they were playing it on the regular radio! We turned it all. The. Way. Up.

And when the oldest lady from church came shuffling out to tell us to turn that rap music off, we took so much smug satisfaction in telling her it was gospel music and we could play it as loud as we wanted and dance as much as we could.

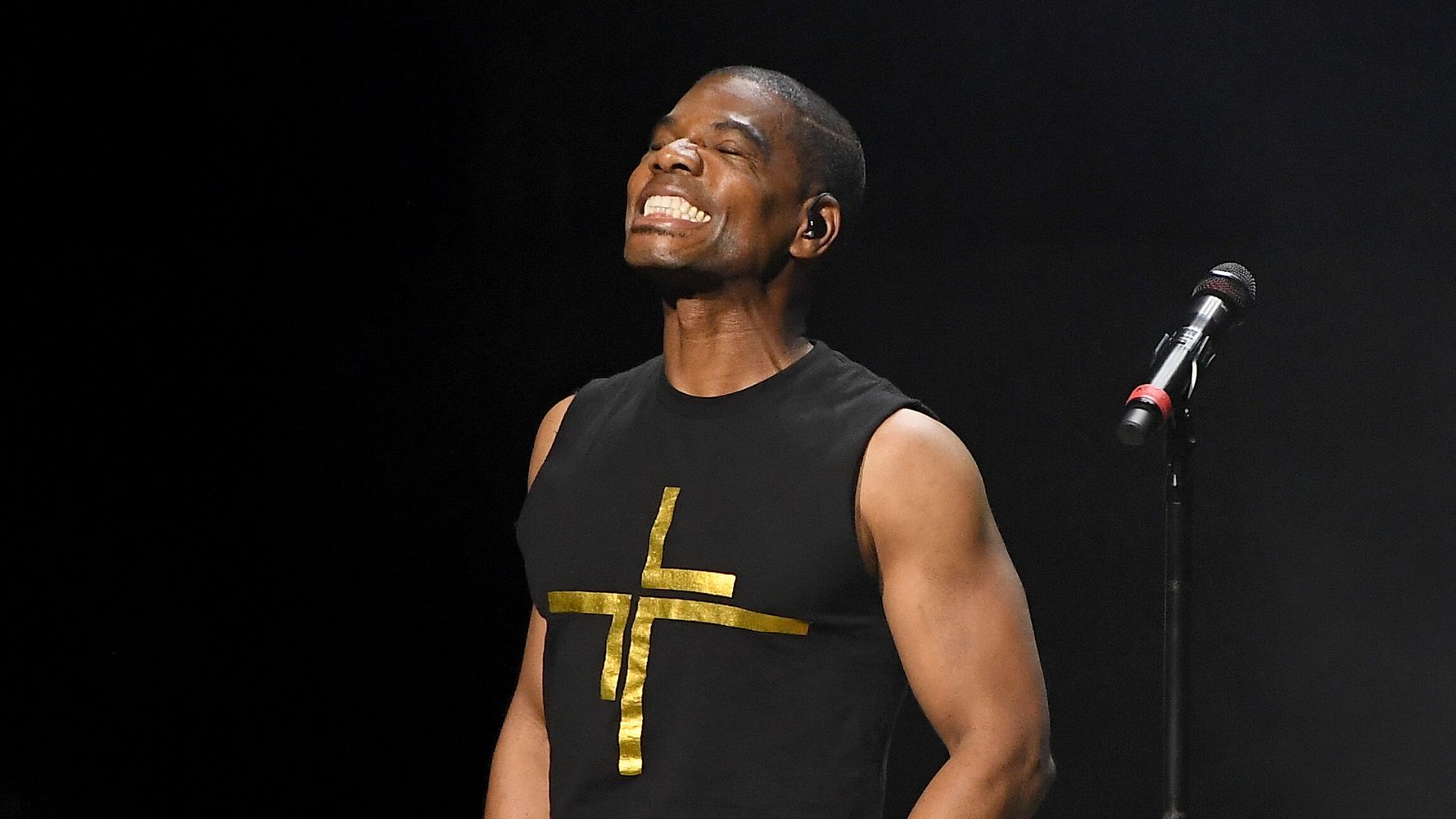

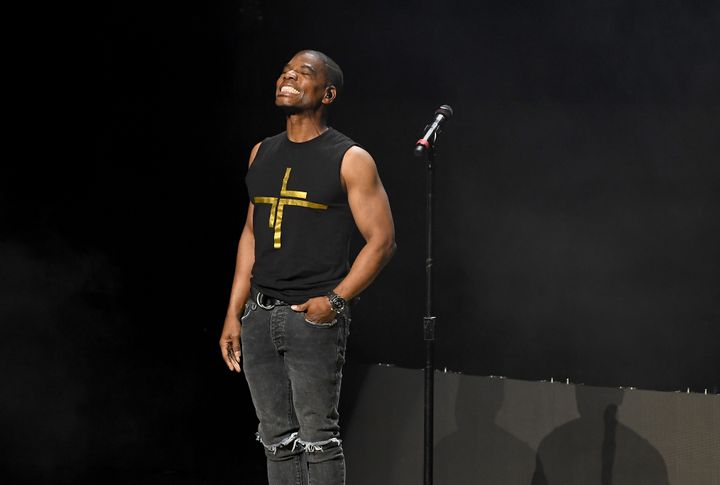

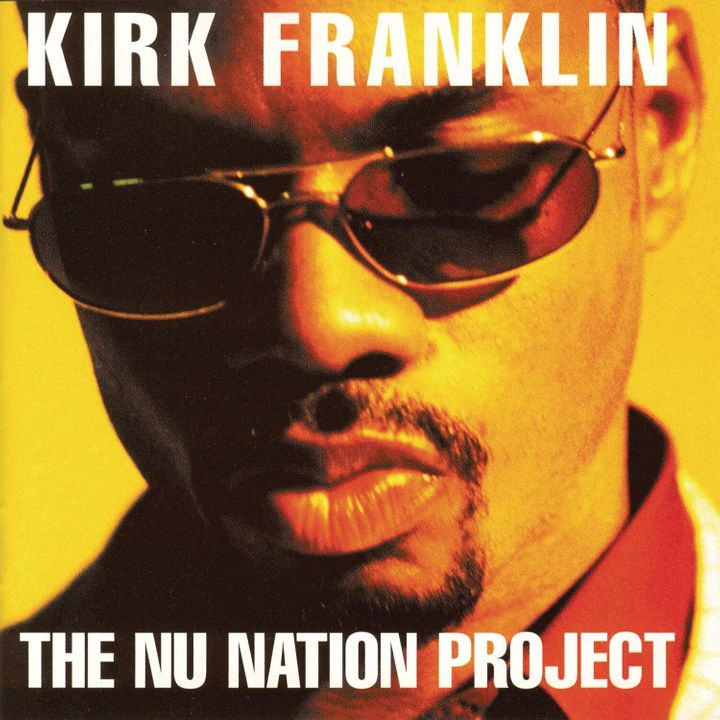

The song was “Revolution,” the latest single by Kirk Franklin, a man who later came to be known as the man who revolutionized the gospel music industry. Before Franklin came along, there wasn’t gospel music that you could dance and shake your booty to and just have fun with.

Franklin’s songs were Jesus-centered, but he used hip-hop, R&B melodies and smooth jazz instrumentals to make us young people want to actually listen to the message in the music. In the early ’90s, he gave us hits like “Stomp” and “Melodies from Heaven.” His videos were featured on MTV and they looked like something Hype Williams might direct; they were so bright, futuristic and full of energy. Franklin sampled Funkadelic, he collaborated with people we knew like Cheryl James of Salt-N-Pepa, Stevie Wonder and Mary J. Blige.

The success of Franklin, along with other artists of the late ’90s like MaryMary and Trin-i-tee 5:7, ushered in a new wave of gospel music that crossed over from the Christian music charts to the Top 100 with danceable tracks and modern music videos that featured cute clothes and style. For the first time, being a church kid didn’t feel so weird and alienating thanks to Franklin’s innovation.

But “Revolution” was a revolutionary track in other ways. The lyrics touched on myriad subjects including premarital sex, racism, lying politicians and people struggling to make ends meet. The song even mentions the environment and pollution, topics that were rare for a gospel song.

“The resolution in ‘Revolution’ was clear: We, the ordinary people, have the power to change our society.”

At the time “Revolution” was released, we were six years out from the LA riots and the beating of Rodney King by police officers, three years out from the polarizing trial of O.J. Simpson, and just nine months from the news that then-President Bill Clinton had lied under oath about sexual misconduct in the White House.

In some ways, 1998 was a lot like 2019 is: There’s distrust in government, ongoing conversations about race, police brutality and sexual harassment, and equality is still a long way away for most U.S. citizens. These are all things we’re still worried about and working on today. And they’re all things I think Jesus would actually give a damn about.

However, the Christianity of today isn’t known for its social justice movements. Quite the opposite, actually. With the continued existence of conversion therapy camps despite evidence that they’re incredibly harmful, the number evangelicals who voted for and support a racist, sexist, xenophobic man for president, anti-abortion legislation being passed, and increased hostility toward immigrants, it’s easy to lose faith in the faith’s ability to do good work.

And at times like this, I’m reminded of the message in “Revolution.” The song is about ushering in a time of change. We have to change the way we relate to each other, change the things we talk about and change our focus to issues of public health and humanity. “Revolution” changed for me what it meant to be a Christian ― to love and care about everyone ― and it continues to inform my life ethic all these years later.

Being a “good Christian” should be about more than sitting in a pew and hating rap music, sexuality or anyone whose beliefs are different. It’s about community and social justice and doing the most for people who have the least power and privilege.

The resolution in “Revolution” was clear: We, the ordinary people, have the power to change our society. And as usual, energized young people are breaking the status quo and leading the way toward radical change.

This Sunday, Franklin’s album The Nu Nation Project and the single “Revolution” turn 21 years old. I know one song from over 20 years ago isn’t going to change everything. But the message reminds me that change is possible if we focus, and if, unlike the shuffling old lady from my church, we’re open to experiencing something different.

[ad_2]

Source link