[ad_1]

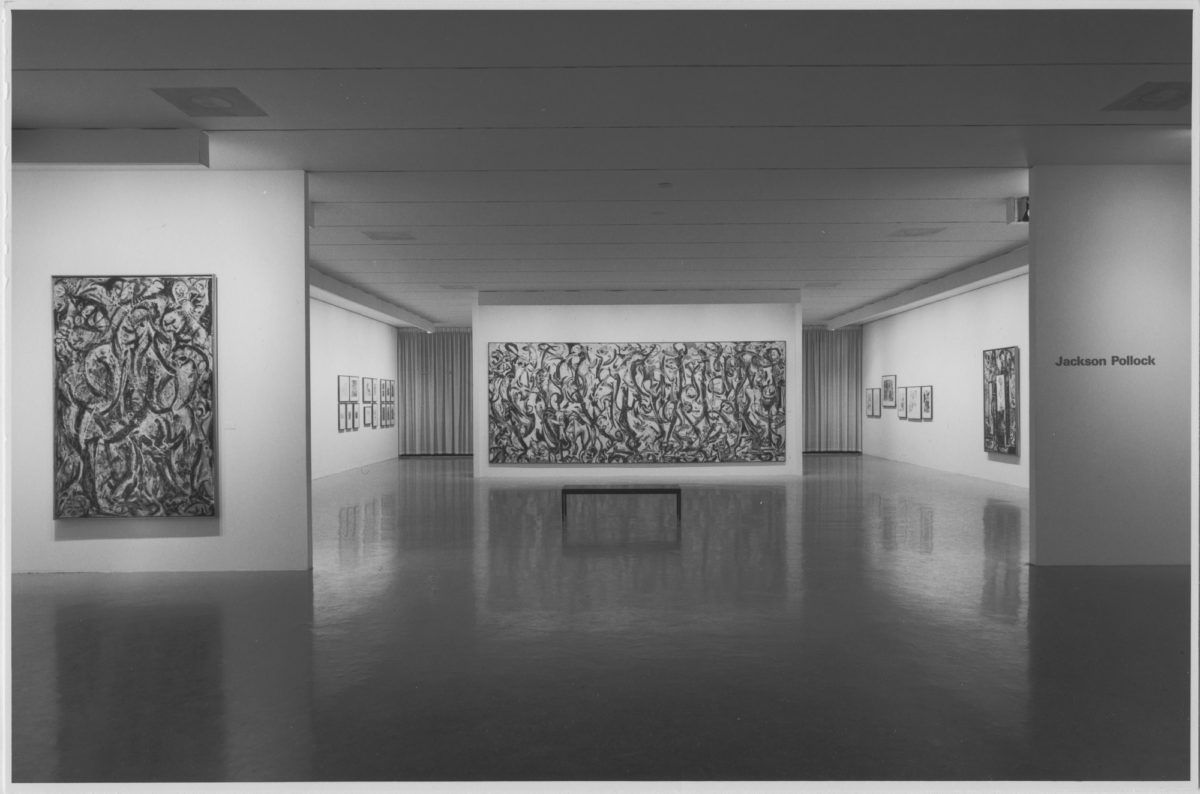

Installation view of “Jackson Pollock,” 1956–57, at Museum of Modern Art, New York.

COURTESY MUSEUM OF MODERN ART

The Museum of Modern Art in New York will reopen after a $450 million renovation and expansion on October 21, marking one of the most dramatic transformations in the institution’s long and storied history. In the run-up to the museum’s next incarnation, ARTnews looks back to important exhibitions from MoMA’s past and offers excerpts from articles and reviews from our archives—moving decade by decade from the museum’s inauguration to the present day. The third edition in this series features eight shows from the 1950s at MoMA, including a posthumous Jackson Pollock survey and the group show that altered the course of American art history.

“Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America”

January 23, 1951–March 25, 1951

The show: Abstraction in the 1950s was associated more with Europe than America until this exhibition—the first survey of its kind—changed the course. With 100 paintings and sculptures spanning the decades since the famed 1913 Armory Show, MoMA aimed to counteract the idea that the abstraction in American bore no historical lineage. Alongside pieces by American modernists like John Marin, Arthur Dove, and Alexander Calder were works by members of the then-nascent Abstract Expressionist group, among them Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, and Mark Rothko.

What ARTnews said: “Walking through these galleries filled with pictures and sculpture, all created in America or by Americans, one is at first fascinated; then disappointed and suspicious; and finally appreciative of contact with greatness. One sees no evolution of a style, but rather a reflection which becomes replaced by an actuality. It as if, while listening to a recording of some music, the musicians themselves came into the room, turned off the phonograph, and finished the piece themselves.” —Thomas B. Hess

Installation view of “8 Automobiles,” 1951, at Museum of Modern Art, New York.

COURTESY MUSEUM OF MODERN ART

“8 Automobiles”

August 28, 1951–November 11, 1951

The show: One of MoMA’s most boundary-pushing early shows, this exhibition assembled an octet of cars presented as art. “Automobiles are hollow, rolling sculpture, and the refinements of their design are fascinating,” the show’s curator, Philip C. Johnson, wrote in the catalogue. It prefigured later exhibitions around the world focused on similar subject matter, including 1998’s “The Art of the Motorcycle” at the Guggenheim Museum in New York.

What ARTnews said: “Eight automobiles that have invaded the museum’s back garden and terrace, bring at last within the discreet jurisdiction of museum walls a kind of design that presses in upon us at every hour of the day, constantly worrying both the mind and the eye with the question of what kind of form should follow this function of pleasure transport through space.” —Dorothy Seckler

“Rouault”

March 31, 1953–May 31, 1953

The show: MoMA offered Georges Rouault, who was among the most popular painters of his day, unprecedented status, making him the subject of multiple retrospectives. His second at MoMA was mounted because, the show’s curator said, it had been “impossible because of the war to obtain for the previous exhibition many important European works by Rouault.” Reports from the time noted that the exhibition was constantly swarmed with crowds.

What ARTnews said: “What once seemed Rouault’s rich, sensuous surfaces have not changed in themselves, but they no longer awaken the same reaction. Rouault seems now to have used heavy pigment and his heavily jeweled color not as a result of ‘action’ while painting towards his inner vision of the finished picture, but actually as a kind of embellishment or ornament, almost as an embroidery on the surface which has nothing to do with the structure beneath.” —Alfred M. Frankfurter

Installation view of “The Family of Man,” 1955, at Museum of Modern Art, New York.

COURTESY MUSEUM OF MODERN ART

“The Family of Man”

January 24, 1955–May 8, 1955

The show: Edward Steichen took the helm of MoMA’s hallowed photography department in 1947 and mounted a number of important themed shows, including this one on the “universal elements and emotions and the oneness of human beings,” as Steichen described it. Steichen showed works by himself as well as others like Dorothea Lange, David Seymour, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank, Lola Alvarez Bravo, Werner Bischof, and August Sander. According to a release put out by the museum at the time, the show broke attendance records for MoMA.

What ARTnews said: “Steichen uses these pictures from all over the globe to speak to his feelings and ideas, his affirmations and apprehensions about the life-cycle of Man in the shaky world of 1955. Because he is an eminent photographer with a passion for his medium, his visual language is often eloquent.” —Edwin Rosskam

Jackson Pollock

December 19, 1956–February 3, 1957

The show: MoMA’s early years were defined by major retrospectives for established modernists—Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and so on—but as Abstract Expressionism came to the fore, the museum began giving new figures major platforms. One such example was this show mounted just four months after Jackson Pollock died. Included were One: Number 31, 1950 (1950), which has been a cornerstone of MoMA’s collection ever since, and the same year’s Autumn Rhythm (Number 30). The show was timely—but too much so for some.

What ARTnews said: “The fact remains, and it cannot be over-emphasized, that it was irresponsible to make the exhibition in this haphazard, semi-apologetic manner. One wonders whether the Museum would have been so cavalier if it had been dealing with a European master (let us say Miro in 1942) . . . perhaps it would have . . . such are the attractions of deadlines.” —Thomas B. Hess

Installation view of “German Art of the 20th Century,” 1957, at Museum of Modern Art, New York.

COURTESY MUSEUM OF MODERN ART

“German Art of the 20th Century”

October 2, 1957–December 1, 1957

The show: This exhibition spanning two floors was the most comprehensive survey of German art in the early postwar era. It began with German Expressionism and went up to the present, touching on the Bauhaus (which had itself been the subject of a legendary 1938 MoMA show) and Neue Sachlichkeit.

What ARTnews said: “The Museum of Modern Art has called its exhibition ‘German Art of the Twentieth Century,’ but there is no doubt that in the mind of the public, this is mainly an Expressionist show—which, indeed, it is, unless one ventures upon an attempt to define the term more closely and does so in a pedantic spirit.” —Edith Hoffmann

“New Images of Man”

September 30, 1959–November 29, 1959

The show: Abstraction was “in” and figuration was “out” when Peter Selz, who died earlier this year at age 100, curated this wide-ranging survey of the various ways artists were portraying the body. In a statement accompanying the show, Selz said he was spotlighting the emotional state of artists such as Francis Bacon, Eduardo Paolozzi, Alberto Giacometti, and more. The show was besieged by critics who viewed it as out of touch with the times.

What ARTnews said: “Rather than being the ‘long awaited’ answer to Abstract-Expressionism, the Museum’s monster show is confusion with wishful thinking buried under its sentimental hide.” —Manny Farber

Installation view of “16 Americans,” 1959–60, at Museum of Modern Art, New York.

COURTESY MUSEUM OF MODERN ART

“16 Americans”

December 16, 1959–February 17, 1960

The show: By the mid-’50s, MoMA’s curators—Dorothy Miller, in particular—had become engaged in the larger project of defining what American contemporary art looked like. (Miller’s landmark show “The New American Painting” was shown internationally in eight countries, and has since been seen as a way of exporting American values abroad during the time of the Cold War.) “16 Americans” was, in some ways, the pinnacle of this initiative, and it was a watershed moment for the American art scene. Works such as Frank Stella’s famed “Die Fahne Hoch!” (1959), “Target” paintings by Jasper Johns, and combines by Robert Rauschenberg were included; all of them offered fruitful ways forward from the Abstract Expressionist aesthetic.

What ARTnews said: “In the Museum of Modern Art’s ‘16 Americans’ exhibition, the hunt is for the ‘new look.’ Despite a catalogue statement to the contrary, the show seems to attempt a demonstration of what is coming after the generation of Pollock, de Kooning, Still, Gottlieb, etc., which the Museum already has pinned into its collection of Famous-Insects-We-Have-Caught.” —Thomas B. Hess

[ad_2]

Source link