[ad_1]

The paintings in Jutta Koether’s recent exhibition at Lévy Gorvy were cooler than you, quicker than you, smarter than you, better read than you, and not afraid to let you know. They moved between enough winking homages to keep professors busy for years: Fauvism, graffiti, Dürer, Ernst, Poussin, Stettheimer, Hartley. The massive Neuer Frau (2019) evoked almost all of these precedents and still found room for a portrait of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, with lips like wax candy and eyes a notch too close together. I’d been trying to come up with a more descriptive name than “sampling” for Koether’s approach to art history. Then I remembered the title of one of the paintings in the show: Some Esoteric Sipping.

It’s a concise description of Koether’s paintings and of her career more generally. She was born in Cologne in 1958 and studied critical theory in Paris with Lacan. Where some rise to fame and fortune on the shoulders of one mentor/collaborator/rival, she had dozens: Sigmar Polke and Martin Kippenberger, both of whom she met in her twenties; Kim Gordon and Tony Conrad, with whom she’s performed music; and a host of old masters. The one trick Koether seems unwilling to learn, or admit she’s learned, is painterly refinement. Instead she opts for a faux-naïf kind of expressionism—or what she called, in a 2016 interview with Benjamin Buchloh, “a slightly exhilarating energy that emerged from the feeling of starting something from scratch.”

Am I writing around Koether’s paintings? Probably, though it’s hard to say how else to proceed. Discussions of her work have tended toward the runic (from David Joselit’s 2009 essay “Painting Beside Itself”: “Instead of attempting to visualize the overall contours of a network, [Koether] actualizes the behavior of objects within networks by demonstrating what I would like to call their transitivity”), or have even gone Ono-esque (from Bob Nickas’s 2003 “How To Write About . . . Jutta Koether”: “Set out a cup of green tea and a ruled notebook”). Such indirect approaches are almost inevitable. To speak of Koether’s “style” seems misleading, since much of it consists of unlearning the skills she acquired while studying art at university. After a while in Lévy Gorvy, in fact, I couldn’t help but admire how successfully she’d managed to shield her work from anything resembling conventional virtuosity—she has a knack for pairing a hot color with an even hotter one until the whole thing seems lukewarm, and it’s a rare line of hers that doesn’t seem too short or too thick or too thin.

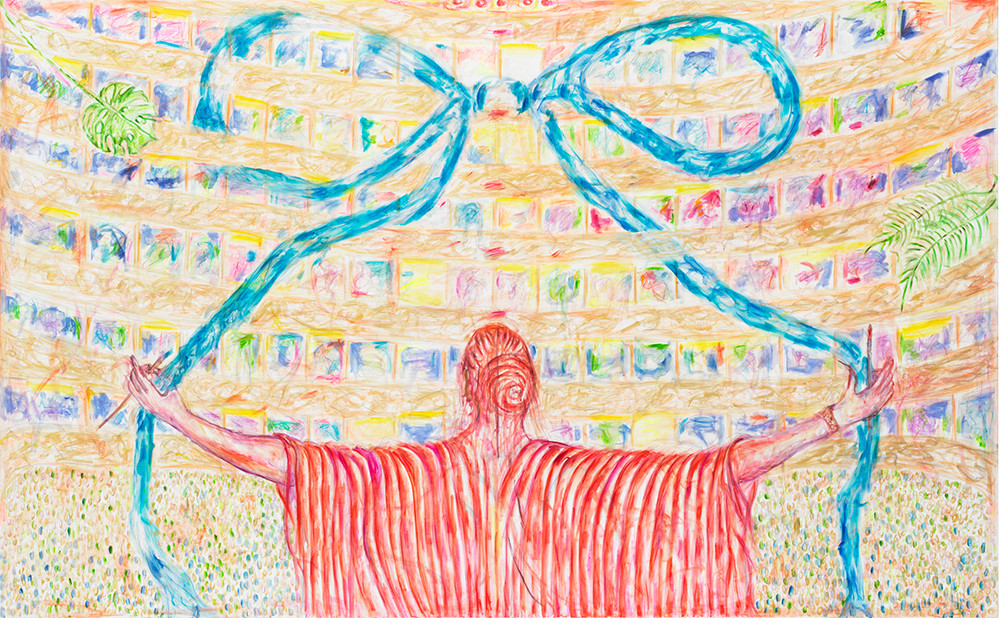

Still, almost any formal characteristic of Koether’s work I can put my finger on is counterbalanced by another. The four large canvases on the gallery’s ground floor, all from 2019, were clothed in delicate, translucent brushstrokes of a kind found more often in smaller, more intimate works. Encore, which shows a woman standing at the center of a crowded opera house-like space, has a cinematic sweep, but this quality is kept in check by the presence of a blue bow that binds near to far and reasserts the picture plane. The paintings on view raised important questions about what the medium can and should do. Some that came to mind as I walked out: What does it mean to sip one’s influences? What are the consequences of engaging with those influences primarily from an intellectual distance—of seeing so much of art history in quotation marks? What is to be gained by abandoning virtuosity for the thicket of remix and repetition? Might this not be a bad trade?

Try as I might, I can’t shake the sense that Koether’s paintings are doing only a sliver of what they’re capable of doing. Too many of the canvases come smothered in cunningly misapplied pigment and vast stretches of bright, inert nothingness. Koether’s work seems premised on the idea that a certain amount of crudeness is essential to art’s power, but the show’s most powerful bits didn’t bother with this pretext. The lower right of Neuer Mann (2019), which depicts a man peeking out from behind a plant, features eloquent color harmonies and inspired embellishments (that checkerboard fabric! those eyes!). I wish Koether would paint like this more often—genuinely, surprisingly, without obscuring her inventions with feints and clever references.

[ad_2]

Source link