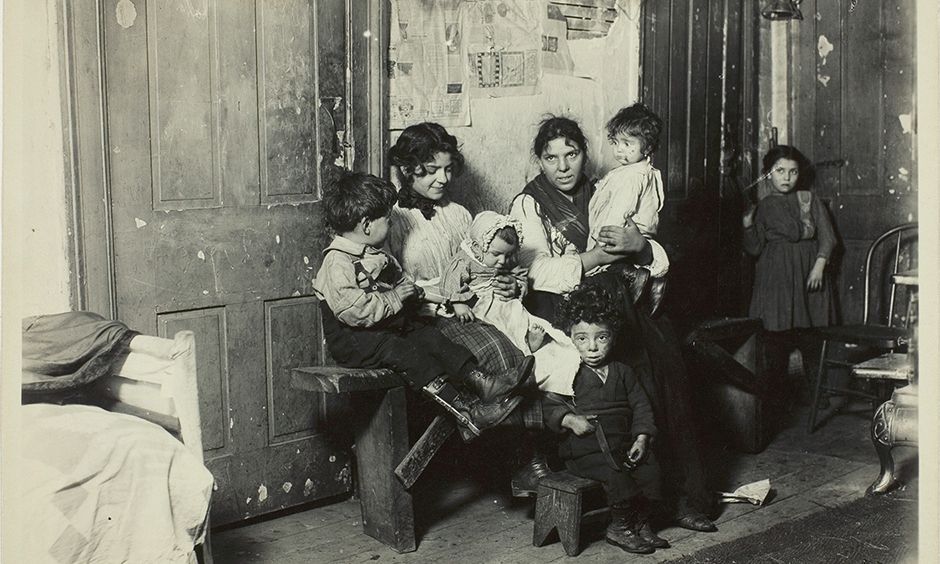

Lewis Wickes Hine’s 1910 photograph of an Italian family in Chicago, from the AIC’s collection. Hine was a sociologist whose photos of poverty-stricken families helped bring about the first child labour laws in the US

Courtesy of Art Institute of Chicago

The impact of the recent $25m gift to the photography department of the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC) will perhaps be most visible to the public with the creation of the Bucksbaum Photography Center, although its completion is bound up in an even larger construction project. When the museum engaged the Barcelona-based design firm Barozzi Veiga in 2019 to begin the process of devising a plan for a campus makeover, it was intended to be a slow process even before the Covid-19 pandemic delayed it.

The museum’s photography collection began auspiciously with a gift in 1949 of 231 images and photogravures from the collection of Alfred Stieglitz (151 by the trailblazer himself), and has grown to nearly 25,000 pieces that include installation art, albums, photobooks and time-based media. The AIC’s commitment to photography dates to 1900, when it hosted the First Annual Photographic Salon; Stieglitz and Clarence H. White, a founder of the Photo-Secession movement, served on the jury.

In the meaty Art Institute of Chicago Field Guide to Photography and Media (Yale University Press, 2023), the museum’s first survey of the collection, co-edited by the former curator Elizabeth Siegel (now the chief curator of the Milwaukee Art Museum, after 25 years at AIC), there are some hints about the department’s existing facilities being less than optimal. For instance, the subterranean galleries were previously part of a café connected to the interior courtyard. In the Modern Wing, the Renzo Piano-designed 2009 expansion, there is a dedicated gallery for photography, thanks again to the generosity of the Bucksbaum family.

Matthew Witkovsky, the chair and curator of photography and media at the museum, who has spearheaded the growth of the photography department since arriving at the AIC in 2009, elaborated on its collecting strategies. (Witkovsky also serves as the museum’s vice-president for strategic art initiatives.) While the acquisition in 2019 of the W. Bruce and Delaney H. Lundberg collection of historic images notably filled one gap in the AIC’s holdings, the collection has slowly been evolving in other areas.

“The Bucksbaum family gift has been made to further visitor experience of the collection. That said, the acquisition of the Lundberg Collection of 500 American daguerreotypes did transform our holdings of 19th-century photography; other initiatives over the past decade and more have made the Art Institute a centre for the study of post-war Japanese photography and media, African Modern and contemporary, and international conceptual art,” Witkovsky says. “European Modernism remains a pillar of the collection and there is more to do to strengthen our attention to Central and Eastern Europe, as the current show of photograms by Hungarian artist János Megyik [until 8 July] makes clear.”

Witkovsky described the collection as highly visitor-oriented. “With the opening of dedicated galleries in 1980 came a study room that is open by appointment to the general public—no special diplomas or credentials needed,” he says, adding: “The entire collection of nearly 25,000 objects is online.”

A gift of this magnitude impacts not only the museum but the city and the photography community at large. Chicago’s roots as a centre for American photography run deep, beginning with the New Bauhaus that started in 1937, with László Moholy-Nagy at the helm, to the Institute of Design’s photography programme. (The school’s eminent alumni includes Harry Callahan, who went on to establish the photography programme at the Rhode Island School of Design in 1961.) Then there is the growing Museum of Contemporary Photography (MoCP) nearby, with around 17,000 works in its collection. The MoCP is part of Columbia College, where the revered photographer Dawoud Bey has been on faculty for more than 20 years.

“Chicago has a very rich history of photography and media—far more widely distributed across the city’s neighbourhoods than has commonly been acknowledged—and attention to it in recent years has diversified appropriately,” Witkovsky says. In 2018, the AIC’s exhibition Never a Lovely So Real—referencing Nelson Algren’s 1951 book Chicago: City on the Make—focused on photojournalists and documentary film-makers on the south and west sides of Chicago. In 2021, the show Subscribe brought attention to the queer photo-illustrated magazine Thing/Think Ink. The museum also partnered with the Chicago collective Floating Museum to commission portraits from ten local photographers.

“The Bucksbaum Photography and Media Center will help the Art Institute mightily in bringing the world to Chicago—and, just as much, in ensuring that Chicago achievements stay visible in the world,” Witkovsky says.