[ad_1]

By Sean Yoes, AFRO Baltimore Editor, [email protected]

It had been brutally hot the week of July 27, 1919 in Chicago, and city residents of all races and ethnicities flocked to the beaches for relief.

On that boiling hot Sunday (July 27), Eugene Williams, a Black teen was one of thousands who traveled to Burroughs Beach on Lake Michigan to cool off.

But, after Williams apparently crossed an invisible line of segregation separating Black and White swimmers, he drew the last few breaths of his young life.

As he waded into “White water,” groups of young White men began hurling rocks at him eventually killing him. The White man who sparked the murderous incident was identified by eyewitnesses on the scene. But, not surprisingly (given the pervasive nature of racist early 20th century law enforcement, rooted firmly in the practice of “slave catching”) White police officers refused to arrest the agitator. In fact, I wouldn’t be shocked if those White cops gave the thug who triggered the melee a pat on the back.

That deadly racist attack against Williams led to days of rioting, pitting gangs of mostly young Black and mostly young White men against each other in open street warfare.

When the violence ended about a week later on Sept. 3, 38 people had been killed; 23 Black, 15 White. Five hundred more people were injured. At least 1,000 Black families lost their homes when they were torched by hooligans.

Racial tensions had been inflamed for almost a year in Chicago before the grisly culmination of hatred and fear in the summer of 1919. After the end of World War I in Nov. 1918, many White servicemen returned from the war to find they had lost their jobs, although Black men who fought in the war often confronted the same challenge. However, the Black population in Chicago more than doubled in 10 short years from 1909 to 1919 (from about 44,000 to over 100,000), which clearly augmented the anxiety of Whites an exasperated ethnic and racial hostilities. But, Chicago wasn’t the only hotbed of racial violence wielded against Blacks during that horrific summer of 1919.

That summer of 1919, race riots also broke out in Washington D.C., Arkansas, Nebraska, Tennessee and Texas. The White terrorist group the Ku Klux Klan was reinvigorated; the Klan organized 64 lynchings in 1918 and 83 in 1919.

In fact, the summer of 1919, also known as “Red Summer,” perhaps was the precursor of the mythical American “race war” so many have dreaded and others have yearned for.

It’s a bloody narrative that resonates today 100 years later.

On Aug. 3, a 21-year-old White gunman drove 10 hours from the suburbs of Dallas to El Paso, Tex., hell bent (literally) on killing Latinos. He slaughtered 22 people and injured 24 others. The murderer (whose name I won’t write in this column), drew upon the same poisonous lexicon as Donald John Trump (whose disparagement of Black and Brown people has been well documented in this column) in describing and demonizing Brown people.

Less than a week earlier, on July 28, another young White man murdered three and injured 12 at the Gilroy Garlic Festival in California, which attracted a largely Latino crowd.

In Oct., 2018 yet, another White man gunned down 11 people and injured six others at the Tree of Life Synagogue during Shabbat morning services in the Squirrel Hill community of Pittsburgh, Penn. This killer shared very similar views on Hispanic immigration as his White brother who attacked El Paso (the synagogue openly supported and sponsored immigrants to America). It was the deadliest attack on the Jewish community in the United States.

The evidence seems clear; anti-immigrant, anti-Black, anti-Brown, antisemitic fervor has been whipped up by many in America, including the 45th President of the United States, particularly over the last year.

How many more angry, young White men are being radicalized on-line, encouraged by the xenophobic, racist language of the 45th president?

How many more are lurking in the shadows waiting for the right moment to trigger the next wave of perfunctory “thoughts and prayers” for another community of besieged grieving Americans?

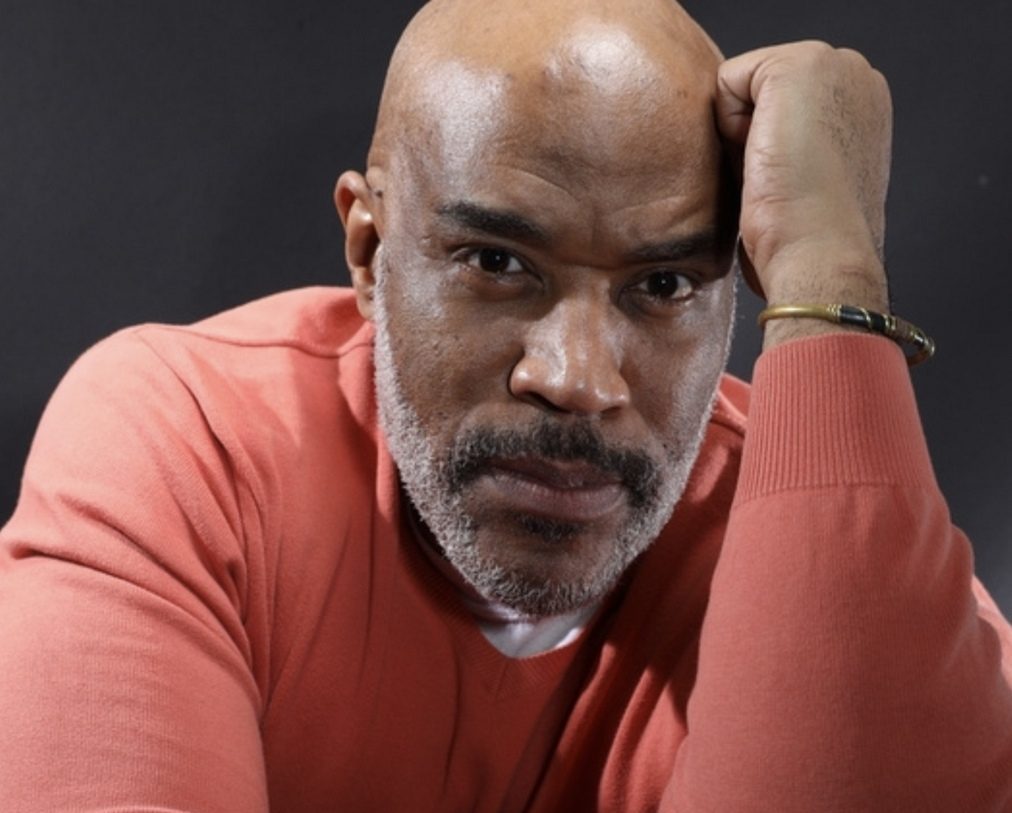

Sean Yoes is the AFRO’s Baltimore editor and the author of Baltimore After Freddie Gray: Real Stories From One of America’s Great Imperiled Cities.

[ad_2]

Source link