[ad_1]

But as we know, history doesn’t stay in one place. My new neighborhood, and playground, is built on a former cotton plantation.

Any other summer, this University of Florida college town would be buzzing with talk of whether the Gators will win the Southeastern Conference title. But with the revival of the Black Lives Matter movement, I can’t ignore that the name of my predominantly White neighborhood invokes a dark history.

A word like “plantation” may seem minor in scope compared to other iterations of America’s racist past and present, but what it represents is larger than the 10 letters that evoke slavery at worst and exclusivity at best.

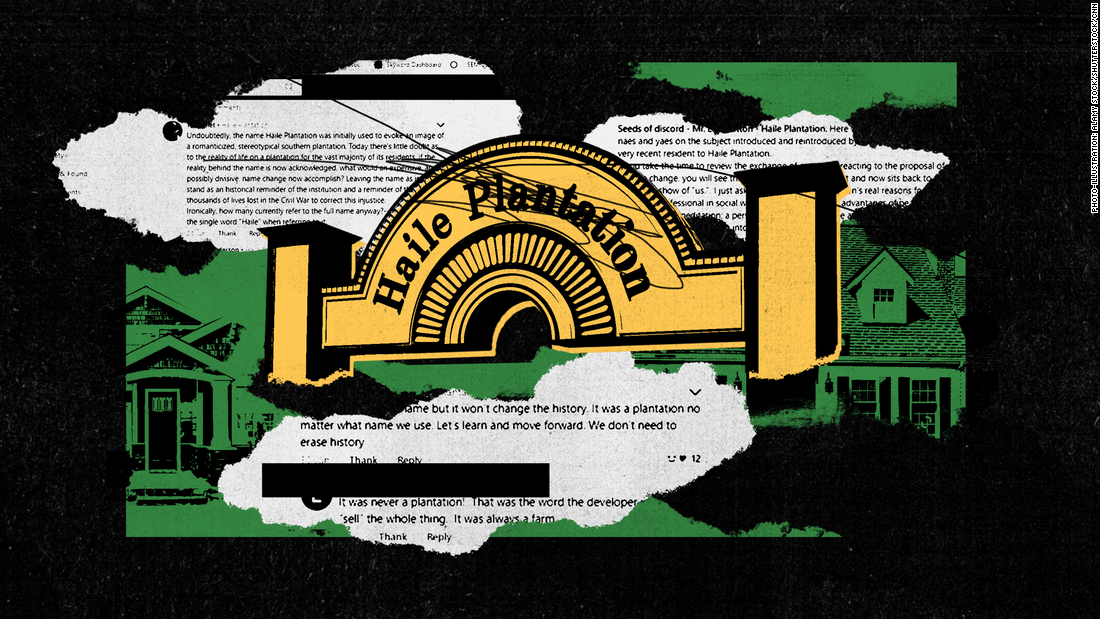

What I deemed a welcoming community when I moved into it (despite its name), feels uncomfortably different to me after someone from my HOA posted on Nextdoor (which groups members into virtual neighborhoods based on their real addresses) about removing “plantation” from Haile Plantation as a consideration toward residents and visitors who are Black, indigenous and people of color (BIPOC).

The responses poured in. While the original post had more than 225 replies from Haile Plantation residents and those in nearby communities, subsequent posts regarding the name change added hundreds more.

“If you don’t like [plantation], leave!” and many variations of “This is ridiculous to even be a conversation. The Instantly Offended crowd need to stop,” were common sentiments from those content with the current name. As I wrote this, the very unofficial Nextdoor poll showed that a majority who voted want to keep “plantation” in the name.

One Black woman, who doesn’t live in Haile Plantation, but is part of my Nextdoor neighborhood remarked on the original post: “Ask someone that’s Black if it’s offensive and then comment. If you aren’t willing to do that, you are the problem and there is nothing me or the post can help you with. My 11-year-old Black son will not be playing outside or jogging through any neighborhood named a plantation, some people care about this and others have openly stated on this post they don’t. And this is the America we live in.”

What does this tell me? More White people who want to be allies need to speak up.

Retaining “plantation” on land that actually was a plantation 166 years ago is giving tribute to the Haile family lifestyle.

A startling number of responses quip with out-of-touch comments like, “As far as I know there are no slaves here anymore and the Union won” and “It bothers me that people are bothered by the name….can we somehow get rid of these people????? I was just fine with everything, I was at peace, and now some people want to make it ugly and unpeaceful. …where there was no ugly before!”

One commenter mockingly suggested renaming Haile Plantation to Haile Revisionist, echoing other replies stating that changing the name changes history. While I admit that without the “plantation” in Haile Plantation, I may have overlooked its history when I moved here, I can understand that not everyone wants a reminder of slavery every time they drive home.

Claiming it’s only a name doesn’t mean that this name isn’t toxic to someone else. And to think that Black Americans are going to forget the history of slavery without the word “plantation” stamped on it is downright ignorant.

This Nextdoor blowup suggests that the outrage has little or nothing to do with the name itself. It’s really about an unwillingness to look through a different lens. The true litmus test for the folks who don’t see an issue with retaining the word “plantation” is to flip the matter to something that affects their heritage.

Would a Jewish family feel comfortable settling in Hitler Homes? Would Russians sign up to live in Communist Commons? Would die-hard Gators fans consider a home in Seminoles’ Village? Are these examples unrealistic and extreme? Yes. But that’s the point.

It is easy to see that denying service to a person of color is racist, that eyeing a Black shopper with skepticism is racist, but glossing over words that seem innocuous but can feel like a splinter that nags every time you turn into a neighborhood or send your kid outside to play is also racist.

Words are triggers and “plantation” is pretty much synonymous with the antebellum South and its slavery roots. The woman who first posted about changing the Haile Plantation name on Nextdoor is not alone in her endeavor.

With all the social media attention on Nextdoor, my HOA formed an exploratory committee of volunteers to feel out whether its 1,500-plus residents care enough about the “plantation” dispute to put it to a vote, or if it’s a fleeting issue soon to be forgotten. At any rate, between tallying surveys and other HOA bureaucracies, the Haile Plantation name change question isn’t likely to be answered any time soon.

It’s easy to ask of someone like me: Well, if you don’t like it, why are you living there? Yes, I could move to another neighborhood, but I also want to make this neighborhood, and neighborhoods like it, live up to their promise of true community.

We cannot move forward and teach our kids about diversity and inclusion if we are pushed out by bullies who say things like, “Deal with it or move up North where all the riots are.” I am staying. It’s time to make a monumental change and remove “plantations” from our neighborhoods.

Real change doesn’t happen in a vacuum. Neighbors across all communities must keep this conversation alive — at book clubs and bars, on Facebook and on FaceTime.

[ad_2]

Source link