[ad_1]

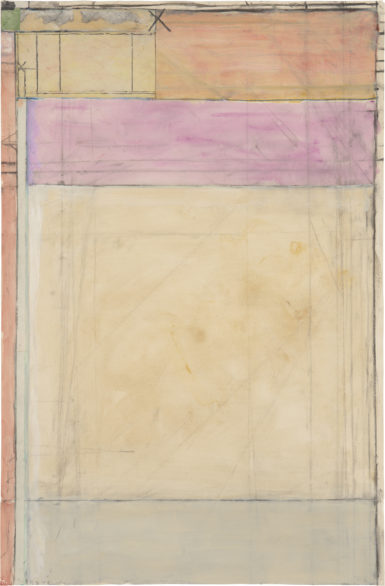

Richard Diebenkorn, Ocean Park No. 22, 1969, oil on canvas.

©VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS/KATHERINE WETZEL

Being in the presence of a great artist can inspire a mix of admiration, anxiety, and awe. For Tony Berlant, an artist who incited such a mélange of emotions was Richard Diebenkorn, the famed painter associated with the Bay Area Figurative Movement during the 1950s and ’60s. Diebenkorn was Berlant’s teacher and mentor at the University of California, Los Angeles, and in an essay that appears in Richard Diebenkorn: A Retrospective (Rizzoli New York), a newly published book that offers an overview of the painter’s work, Berlant recalls his time learning from a master. The essay, in which Berlant recalls the “struggle” of Diebenkorn’s way of working and the “years of paint built up from his hands” on his palette knife, follows below. —The Editors of ARTnews

I was already impressed by the paintings of Dick Diebenkorn when I first saw him in a photograph through a magnifying glass in a magazine article that showed him in his studio. I saw a calm but determined alchemist. The image invoked for me the vision of an artist working in such a space finding pleasure in the ability to create art as a manifestation of oneself. Work that would not just exist but live on, filled with the presence of its maker.

It was about three years later when we met. I was an undergraduate at the University of California, Los Angeles, taking summer classes in figure painting. Dick was the teacher, the annual famous visiting artist. The classes were intense. Figure drawing at eight o’clock in the morning, followed by two painting classes back-to-back, using the same model. Dick felt there was not enough time in the six weeks to work significantly with each student’s individual style so he thought it would be more productive to show us how he worked. The poses and surroundings were deliberately set up to be “Diebenkorn-like.” Each student had to complete a large painting every day.

As the years passed, Dick became a mentor and friend. When I was teaching at UCLA myself, I shared an office with him and Bill Brice. Although he was a very private person, he felt a responsibility to teach. I came to feel that teaching gave him an expanded human contact, a place to go other than the studio and the very precious life he shared with his wife, Phyllis, at their home on Amalfi Drive overlooking Santa Monica Canyon and the sea beyond.

During the years he was teaching, Dick told me that his concentration while painting might be interrupted by thinking about something he had said to a student the day before that might need to be revisited. He avoided the dogmatic and made it apparent that the working process was to be valued above analysis.

Dick’s first Ocean Park studio was one door over and right behind my house. It was on the second floor of an old brick building on the corner of Hill and Main Streets. From my backyard I could yell across an adjoining vacant lot and he would appear at an open factory-style window. As I walked around the corner, I often glanced up and, from an oblique angle, saw his hand and arm painting. The studio overlooked a curtain of trees and fragments of the houses beyond. Occasionally I was invited to visit.

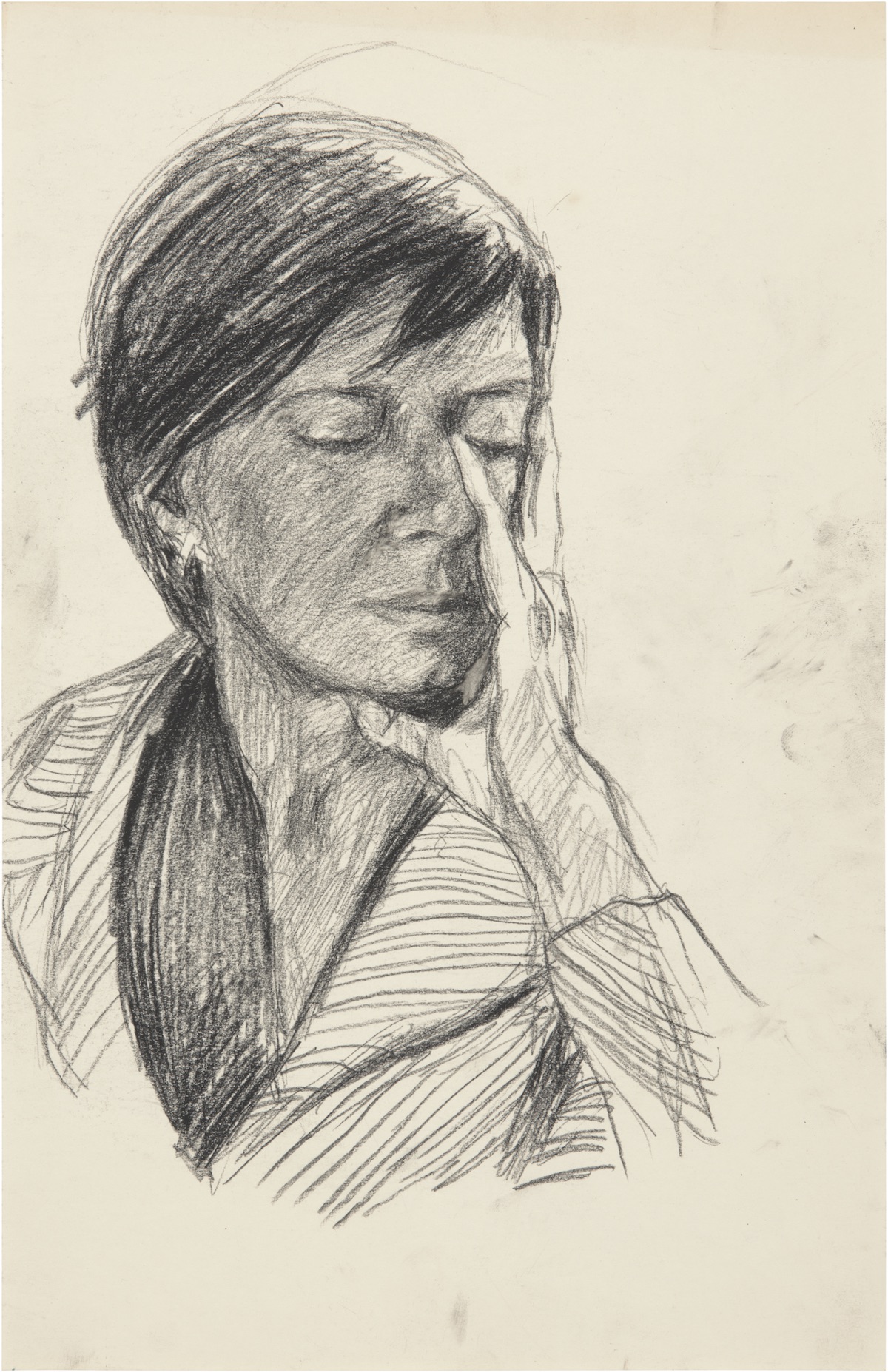

Richard Diebenkorn, Untitled, ca. 1960–66, charcoal on paper.

©RICHARD DIEBENKORN FOUNDATION

After Dick retired from teaching, I would see him from my house across the empty lot arrive Monday through Saturday at about ten o’clock. After parking he would get out of his dark blue Porsche Carrera with a brown paper bag lunch and walk into the building. He would work until the light faded at the end of the day, but on Sundays he stayed just half a day.

Dick shared the floor with Sam Francis who had the front half, facing the ocean. Sam was rarely present as he used the space only to make oversized paintings. Charles (Chaz) Garabedian worked in half of the space in back next to Dick. The studio building faced Main Street, which at the time was a semi skid row a block from the beach, shared by artists and bars like the Pink Elephant. On the same block or nearby were the studios of James Turrell, Les Biller, Sam Amato, Larry Bell, Robert Irwin, Vija Celmins, Billy Al Bengston, Maxwell Hendler, Ed Moses, Alexis Smith, Frank Gehry, Charles Arnoldi, Tom Wudl, Chris Burden, Karen Carson, Lance Richbourg, and many others. My friend the self-taught visionary painter Ed Newell lived in various outdoor places nearby and occasionally in an abandoned crate next to the back door of my studio.

Dick was highly respected by all, but there was almost no interaction with the artists who lived and worked close by. He spoke with contempt of the “kind of artist who had a phone in their studio,” something he scoffed at as antithetical to an artist’s concentration. After Arnold Schwarzenegger bought the building, he turned the second-floor studios into his office, forcing the artists to move on.

Dick’s eventual studio was a few blocks north and on the opposite side of the street. It was especially private, as he built a two-story concrete-block space for himself and did not share it. He used the ground floor for storage and worked upstairs. From inside, through a grid of factory windows, you could view the upper edge of building rooftops across the street, then houses clustered on the hill above, and beyond that, the sky. The overall visual configuration seemed to be reflected in the structure of his Ocean Park paintings.

One could see Dick’s footprints clearly present on the steep dusty stairs up to the studio, making it clear that it was rare for anyone but himself to enter that private space. He would assert with credibility that the studio floor had never been swept. Thick dust accumulated along the line where the walls met the floor; paint-splattered cardboard covered the floor, producing a very comfortable surface to walk on. I was always struck by the quality of light in his studios. It had a suffused clarity, with a sense of quiet energy flooding the spaces.

Richard Diebenkorn, Untitled, 1978, acrylic, charcoal, crayon, and pasted paper on joined paper.

©RICHARD DIEBENKORN FOUNDATION

In the middle of the studio stood a chair, to the legs of which Dick added small wood extensions to raise it up to the ideal level when he was seated to look at his work. Until he stopped smoking, extinguished cigarette butts were piled up and formed a pyramid shape in the ashtray that sat on a small adjoining table. His palette was a large sheet of glass on a table. Paint had gradually built up in thick clusters that overhung the edges like stalactites. A palette knife had years of paint built up from his hands, producing an impression of his grip on the handle.

With my help, Dick carried his paintings one by one out of a rack and placed each in turn on a studio wall. We would look at each one in silence for about fifteen minutes or more and then go on to the next. Conversation was not part of this shared experience. His studios had the atmosphere of a monk’s cell, a place without schedules or interruptions.

Works on paper were hung together on another wall. Although many wonderful drawings were lightly worked, Dick seemed always to select the heavily worked ones for exhibition. He told me that he missed the old days when he could wait two years before he exhibited those works he considered done. He wanted to live with them before releasing them out into the world, something that had changed thanks to increased demand from galleries.

Struggle was an innate part of how he worked. Always highly self-critical, he allowed himself to question and doubt everything he did. A yin-yang balance between impulse and revision is felt in all his work, and his intense struggle pursuing personal visual perfection was central to his realizing the glowing, radiant calm and balance of his Ocean Park paintings and drawings. One time he told me that he had hit a creative wall and feared that “I’ll never be able to complete another painting.” My response was to ask if there was another painter in the whole world that he felt was as good as he was. A puzzled look came across his face and a few moments later, he started laughing.

Dick exemplified the artist who worked for an audience of one. His shifts from abstraction to figuration and back came through impulse, rather than theory. When he moved from the figure to the Ocean Park abstract paintings, he told me that the catalyst for these works came from looking down at the patterns of landscape while flying back and forth to Washington, D.C., for the National Endowment for the Arts selection committee. When he and Phyllis left Los Angeles in 1988 for the isolated beauty of Healdsburg in Northern California, he told me that every major shift in his work was linked to a shift in physical location and that it was time for a change. He also noted that just the task of fending off people was now too much of an effort. He missed the days when collectors did not want to eat meals with artists.

Although we sometimes had dinner together, I never saw Dick out in the art scene at parties or openings. He preferred absolute focus within a private, undisturbed place. He slowly built his paintings through a process of sustained looking and touching, the endless thin layers of paint and erased corrections creating a kind of visionary skin—a manifestation of self—in essence, a distilled presence.

From Richard Diebenkorn: A Retrospective, by Sasha Nicholas, published by Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., New York, 2019. Reproduced by permission.

[ad_2]

Source link