[ad_1]

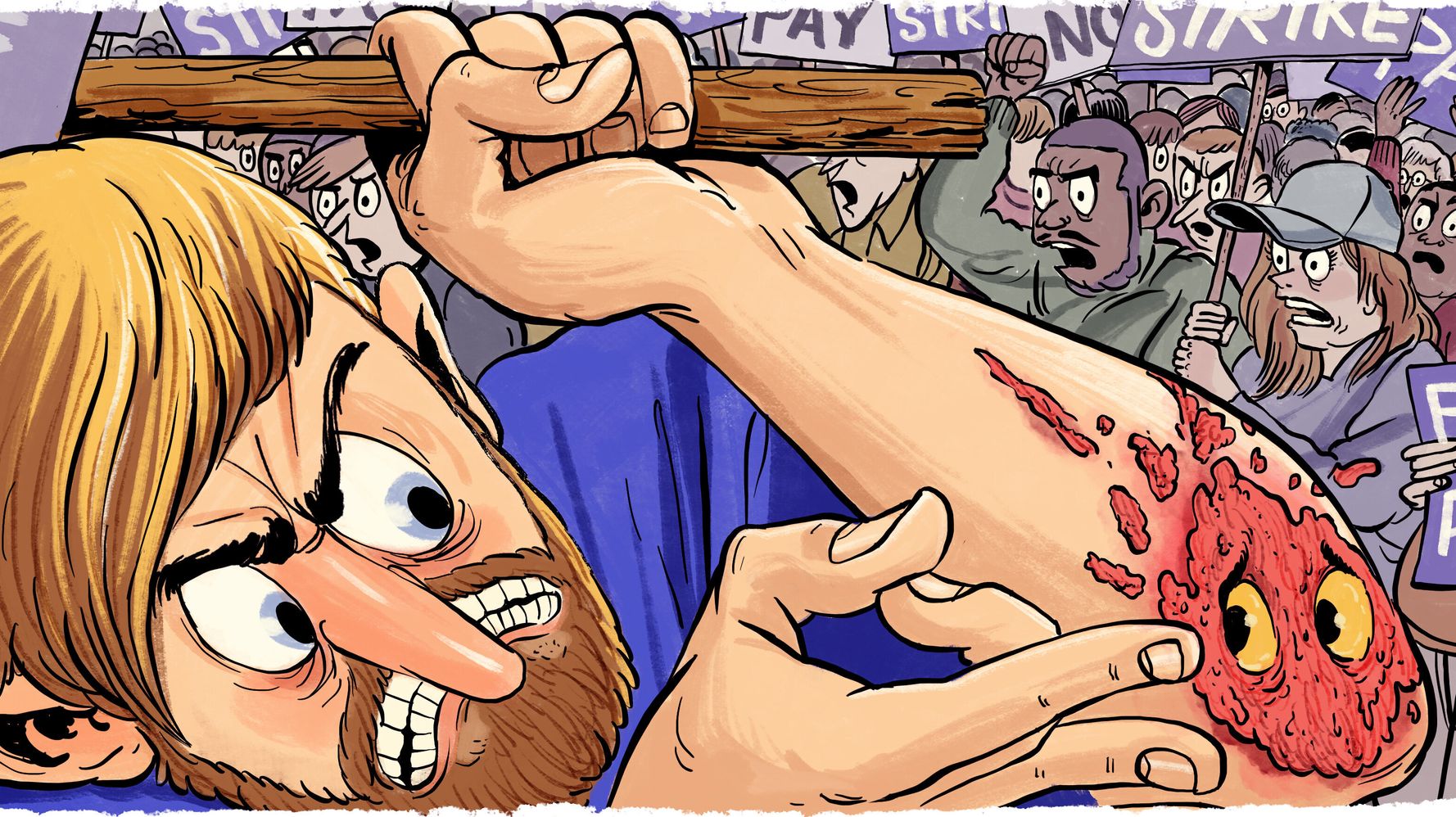

When it comes to coping with the degradations of late capitalism, nothing beats a meticulous skin care regimen. Specifically: scrubbing out scabs.

Yep, the epithet “scab” is back — and more reviled than ever. The magnifying mirror is out, and we’re all gazing at the mangy pelt of our workforce without mercy. Publicly refusing to support your colleagues’ union push? Scab. Ordering a pack of tube socks, a Kindle and a yoga mat on Amazon Prime Day amid warehouse strikes? Scab. Booking your NBA team a stay at a Marriott as the hotel chain’s workers walk off the job protesting for better conditions and wages? Scab. Blogging for Deadspin in the aftermath of the entire editorial staff resigning in protest of management? Definitely a scab!

Amid a resurgence of labor organizing and class consciousness, the word “scab” seems to have been revitalized and re-mainstreamed. In the process, it even seems to have evolved into something more capacious by default. Recently, the word has been flung at all perceived class traitors — not just strikebreakers but also customers who cross picket lines and people who espouse anti-labor sentiments. For a new generation of union enthusiasts and leftists, “scab” holds both the power of social shame and the flexibility to stigmatize all types of working-class treachery.

What is the scab?

At the turn of the 20th century, novelist Jack London composed a polemic on the scab so vicious and simultaneously educational that it has remained the definitive text on scabs ever since. In “The Scab,” he offers “what may be called a technical definition, worded in commercial terms … that a scab is one who gives more value for the same price than another.” In practice, it has been used in labor circles as an epithet for a strikebreaking worker since well before London’s time, and dictionary definitions tend to narrowly define the term this way. Oxford Dictionaries, for example, says a scab is “a person who refuses to strike or join a trade union or who takes the place of a striking worker.”

As an insult, “scab” is not only exquisitely gross but also apt: Where union actions aim to make the employer bleed money, the scab stanches the flow. In his musings, London emphasized the visceral shame conveyed by the word. “It is not good to give most for least, not good to be a scab,” he wrote. “The word has gained universal opprobrium.”

This makes the word sound vicious, even violent — and it is, despite the glowing ideals that motivate many who use it. “Scab” is wielded to prevent others who are struggling under capitalism from undermining striking laborers, even at the expense of their own quest for survival.

London didn’t idealize strikebreakers’ union opponents, describing how they would happily maim a scab in the name of protecting their own wages. He depicted the scab as a symptom of the cutthroat struggle for survival dictated by the economic conditions scabs and strikers alike lived under.

“He does not scab because he wants to scab,” London wrote. “It is because he cannot get work on the same terms as they that he is a scab.” Slaves, he argued, were effectively scabs; women, undocumented immigrants and people of color also fall under his capacious definition, as they are offered lower pay for the same work. Even a worker who receives a raise, which his employer pays for by jacking up the prices of his products, has become a scab; the higher prices of goods have reduced the buying power of other workers’ compensation.

In fact, we are almost all unwitting scabs in London’s view, all in some way providing more value for less than someone else and in that way undercutting our fellow workers. That is, of course, how capitalism works: Only the most privileged are exempted from the bloody battle for survival.

If held to, though, the bonds of solidarity benefit everyone in the end; scabs may reap short-term benefits, but only a united labor movement can weaken the power of capital and uplift all workers. Building that coalition also relies on centering and supporting those most mistreated and vulnerable — those London framed as predisposed to scab.

“Nothing should have more moral or strategic importance to the labor movement than organizing that prioritizes the safety, leadership and demands of marginalized people, both in how organizing is carried out and its ultimate objective,” said Daniel Gross, a longtime labor organizer and the founder and executive director of Brandworkers. “Strike fund policies, strike mutual aid and strike support networks should take into account the marginalized identities of strikers that intersect with class and meet as many needs as possible.”

But the stick matters, along with the carrot; the stink left by an insult like “scab” serves a strategic purpose.

“There’s an establishment of political and moral norms that is being upheld by demanding that people not cross the picket lines, and ‘scab’ is a way to affix a term to that person who has engaged in this morally unforgivable act,” Micah Uetricht, managing editor of Jacobin, told HuffPost in a phone conversation. Not only does this strategically discourage strikebreaking, he said, it honors “the act of courage and bravery that is required for someone to go on strike.”

But in recent decades, with union membership dwindling and labor interests in retreat, “scab” had begun to lose its edge. As Silicon Valley’s burst of startups and disruptive platforms became the face of economic success in America, and many workers were relegated to gig work rather than traditional employment, a cultural mystique congealed around the very idea of working oneself ragged in order to nose ahead in the rat race. When everyone is an entrepreneur or a personal brand in the making, giving the most for the least simply looks like an investment — even if, in practice, there are still a handful of bosses at the top raking in the real profits. Scabs themselves didn’t disappear over the past couple of decades, but lately, outside of solidly unionized shops, scabbing and scab-adjacent behavior has often seemed to pass without a negative remark, rebranded in Fiverr ads and WeWork decor as “hustle” or “the grind” or “working for exposure.”

“Scab doesn’t perform at the same level of rhetorical labor as it did at the dawn of the twentieth century, when it was considered a term so vile as to cause shame,” wrote Stephanie A. Smith in her 2006 book “Household Words.” Though she acknowledged that the term continued to be used with venom by labor organizers, she argued that in mainstream, non-activist spaces, the stigma had attenuated.

Thirteen years later, that may be changing.

Scab has become a Very Online Left insult.

“#DeleteUber is introducing a new generation to the horror of scabbing,” wrote Sarah Jaffe in The Washington Post in 2017. She was right. The word is now all over headlines and social media. Coverage of the ongoing Writers Guild dispute and Chicago teachers strike litigates whether anyone is scabbing — and whether that’s bad or, uh, maybe heroic. At least three headlines called center-left columnist Jonathan Chait a scab in late 2018 after he responded to a union campaign among his colleagues at New York Magazine by publicly sucking up to management. When Uber and Lyft drivers protested in advance of Uber’s IPO this spring, for example, they asked customers to abstain from hailing rides through the apps on the strike day. When Amazon workers struck on Prime Day this summer, many labor groups encouraged consumers to avoid the site. In both cases, Twitter was flooded with tweets encouraging readers not to be “scabs” by buying from the boycotted companies.

Once largely the jargon of union members and organizers, “scab” has lately become common parlance for the Very Online Left — a popularization rooted in the rise of a passionate new leftist wave, a rejuvenated union movement and social media.

The thirst among young Americans for an answer to the sins of unfettered capitalism — a system that has presented most of them with lives of grueling precarity and nonstop labor — is fervid and growing. With wages stagnant and many Americans leading economically precarious lives, the nation’s romance with Silicon Valley and Wall Street entrepreneurs has begun to wither. Startups earned billion-dollar evaluations by promising to “disrupt” entrenched industries, often largely achieved by cutting labor costs by relying on independent contractors with no union protections or benefits.

Now there’s pushback. After bottoming out in 2009, public approval of unions has recently polled at its highest levels in decades. The push to unionize new industries and workplaces has been well-publicized in digital media, but it’s also made waves in the hotel and hospitality, restaurant and domestic care industries.

“To me, there’s no question that there’s a significant turn to workplace organizing taking place,” Gross said. “The millennial and post-millennial generations have come of age amid economic and climate crisis, extreme income and wealth hoarding by elites, and dynamic movements like Occupy, Black Lives Matter, Standing Rock, as well as the upsurge of organized dissent after the election of Trump.”

And where there are labor actions, the word “scab” will always be found. But language is elastic, and as “scab” finds new prominence in a new era’s labor movement, the word itself has also begun to evolve.

“The meaning of the word scab has expanded over the years from the century-old meaning: strikebreaker,” Nelson Lichtenstein, a professor of history at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and director of its Center for Work, Labor, and Democracy, told HuffPost via email. When Uber riders, not just Uber drivers, are targeted as scabs, it’s clear that the insult holds a meaning beyond simply a replacement or non-union worker — it means anyone, including a customer, who crosses the picket line, opposes unions or undercuts fellow workers.

It was also evident in last week’s brief but intense backlash to Alan Goldsher, a freelance journalist who submitted a pitch to Deadspin after seeing the staff’s mass resignation over a high-handed “stick to sports” mandate from the new G/O Media management. His blog, “If Only Kevin Durant Had Beaten the Shit Out of Draymond Green,” ended up being the first post published after the exodus, and his tweet promoting the piece was quickly ratioed by fellow journalists and others calling him a scab. Despite the fact that there was no actual strike or picket line to cross, the word “scab,” for many, clearly captured the sense that to write for Deadspin would be to dishonor the principled sacrifice made by its editorial staff.

“Setting aside whatever feelings I might have about the technical meaning of the word ‘scab’ and its relative applicability in this specific situation — the power of the word “scab” comes not from the definition one finds in the dictionary but from its application in specific circumstances,” Brendan O’Connor, a freelance journalist and member of the Freelance Solidarity Project’s organizing committee, told HuffPost. “The fact that there was such an outpouring of support for the Deadspin and G/O workers is a great thing.”

Erik Loomis, a historian at the University of Rhode Island and author of “A History of America in Ten Strikes,” told HuffPost that the decline of the labor movement followed by the rise of the new leftist movement in recent years has, he believes, led to the word being fuzzily resurrected.

“When you had strikes and strikebreakers as a major part of American life, scab meant something very specific,” he said. “The term ‘scab’ is something that has meaning to a lot of people, but it means more like ‘someone who doesn’t stand with the working class’ rather than ‘strikebreaker.’”

Others aren’t entirely convinced. “At this current point, people understand what a ‘scab’ is, but I have not heard the word referenced as much as in previous eras,” Meredith Katz, assistant professor of sociology at Virginia Commonwealth University, told HuffPost. She suggested that it would be a stretch to apply “scab” to a consumer crossing a picket line.

Gross, conversely, argued that no such shift has taken place because “scab” always applied to customers who ignored labor-driven boycotts. Perhaps this was simply more visible on the physical frontlines.

“When I was on the strike line with grocery workers in a protracted strike in 2003, they were definitely referring to customers crossing the picket line as scabs and I joined them happily in doing so,” he told HuffPost.

Even “Seinfeld” put this definition into action all the way back in the ’90s. In a scene Uetricht now enjoys using as a Twitter meme, Kramer castigates his friend Elaine for patronizing a bagel shop where he once worked — he’s been on strike for 12 years. “You’re siding with management?” he demands, incredulous. “Scab! Scab! Scab!”

Can consumers be scabs, too?

But though it may have just been a kooky Kramer bit in that 1997 episode, it’s now a regular part of the discourse: Consumers are being called scabs, in public, with great regularity. Uber summoners, Amazon shoppers, even those NBA teams staying at the Marriott — these aren’t strikebreakers per se, but they have taken plenty of heat for scabbing. Calling shoppers who cross picket lines “scabs” suggests a thirst for a broader-based resistance to misbehaving corporations, one that blends labor strikes with consumer boycotts to make a deeper dent in the bottom line.

“People are frustrated in our society,” Uetricht said. “They feel like they don’t have a lot of ability to change the absolute nightmare world that we live in, and joining in on a consumer boycott like that is a way to feel like you actually are making an impact.”

It also may be a response to the ungainly spread of the gig economy and globalized corporations. Organizing an airtight strike among Uber contractors who don’t share a workplace or even a personal relationship with other workers may be near-impossible, noted Uetricht, so “when there is a small group of workers who are willing to take that action, it makes sense to build their actions to be bigger, to include this consumer boycott angle.”

Nor is there a clear distinction between the groups to begin with. Workers, as Gross pointed out, are also consumers; the two categories are by no means distinct, and joint action between them is not new. Gross emphasized that consumers should “take note of what workers in struggle are doing and go with that. Trust workers.” Sometimes this may involve a boycott.

“Historically, we have seen that producer-consumer alliances have frequently benefited workers. For example, the UFW Delano Grape Strike and Boycott,” Katz told HuffPost. That strike, a joint effort by Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez’s United Farm Workers and the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee, included national protests and a successful campaign for a table-grape boycott; after five years, grape growers agreed to a contract that ended the strike.

But Katz noted that, because of increasing globalization, “we are distanced from those who produce or even distribute our goods. Re-establishing those connections is one aspect of improving working conditions.” And she does see a shift in that direction.

“Consumers are becoming more aware of the deleterious conditions of producers and workers,” she told HuffPost. “Millennials want to know what corporations are doing harm and suggestions for which ones to support.”

Even as the tentacles of massive corporations like Amazon seem harder to evade, she pointed out, “the easy identification of these monopolies (Amazon, GE, etc.) makes it easier to identify targets for anti-capital organizing.” It’s actually relatively simple to blast out a social media post encouraging people to avoid Amazon for a few days (though this is complicated by how many other brands Amazon owns) or to delete Uber from their phones — they’re companies that consumers interact with frequently and, in many cases, directly.

Scabbing on social

Whereas once the picket line may have been at the workplace — and frequently a workplace like a factory, where only workers are likely to be physically present — now the picket line can be anywhere. The same smartphone that allows you to summon an Uber or order Postmates can also pull up a stream of pro-strike commentary. A pithy insult like “scab” is perfectly suited for enforcing social norms on social platforms; like another epithet popular on these platforms, “cuck,” it’s a punchy one-syllable word with spiky edges. Snarky, visceral, eminently memeable, it’s easy to imagine delivered in a hiss, dripping in disdain.

Sure, Twitter isn’t everything. But it would also be a mistake to dismiss the burgeoning chatter of Twitter socialists and union partisans. Loomis argued that communities fostered online, often among people who haven’t even met, have fueled the widespread new enthusiasm for leftist politics.

“While I would agree, as many organizers would say, that there’s nothing like actually physically being with somebody in a protest or something like that for organizing potential and the spirit of solidarity that that creates,” Loomis said, “I don’t think you have a revived left in this way without the Internet.”

Social media’s reach offers the potential to rapidly mainstream language and ideas once found in niche communities — and immediately notify people who betray the ideal of solidarity that somewhere out there, people think their behavior really sucks.

“Before social media, if you heard about a strike, and you heard about somebody crossing the picket line or not obeying the boycott of the company or whatever, you’d just say to yourself, ‘Ahh, those fucking scabs,’” Uetricht said, “but now you can tweet it! In fact, you can tweet directly at the scabs themselves!”

And sometimes, just maybe, tweeting it directly at the scabs can even help change their minds.

On Friday, as torrents of current and former G/O Media staffers and their supporters tweeted “scab” at Goldsher, O’Connor instead extended a friendly invitation to the besieged writer to talk about freelancer organizing. The two spoke on the phone, and Goldsher later tweeted an apologetic and heartfelt thread announcing that he’d no longer write for Deadspin.

“I had no idea this would move so many people, that you were all this passionate… in my 20-plus years as a freelancer, I never had ANY significant support from colleagues,” he wrote. “In a weird way, I have to thank you guys for all the insults and cries of ‘scab.’ If that hadn’t have happened, I would’ve had no clue that the general public felt this way.”

In a phone conversation on Tuesday, Goldsher offered a more critical take on “the insults and cries of ‘scab.’” Being the target of such a flood of nasty insults was awful, he explained, but it also wasn’t the reason he changed his mind. “It wasn’t the word ‘scab’ that really impacted me. It was the stuff from the other journalists… that’s what impacted me,” he told HuffPost. “People saying, ‘Dude, this is not the right thing to do,’ instead of just calling me names.”

“There are times when it is appropriate to call someone a scab, or to harangue a boss, or to chant and cheer in the streets — but we have to be deliberate about when and how we do so,” O’Connor told HuffPost. “In other words, it behooves us to give people the opportunity to do the right thing. And if they don’t, then we can yell at them.”

Even if the insults didn’t faze him, Goldsher emphasized, again and again, that he was struck by seeing such a powerful response from his fellow journalists. “It goes back to the passion,” he said. “There were so many people that were passionate about the union aspect of it.” He saw, in that passion, the possibility of a community.

Calling someone a scab may not always be the kindest or most tactical choice. It’s certainly not enough to build a labor movement on. But even though it’s only one weapon in the arsenal, it’s a natural outpouring of that passion, of a righteous and emotional conviction in the idea of workers standing together against owners and bosses. And for an ascendant labor movement, that passion is surely indispensable.

REAL LIFE. REAL NEWS. REAL VOICES.

Help us tell more of the stories that matter from voices that too often remain unheard.

[ad_2]

Source link