[ad_1]

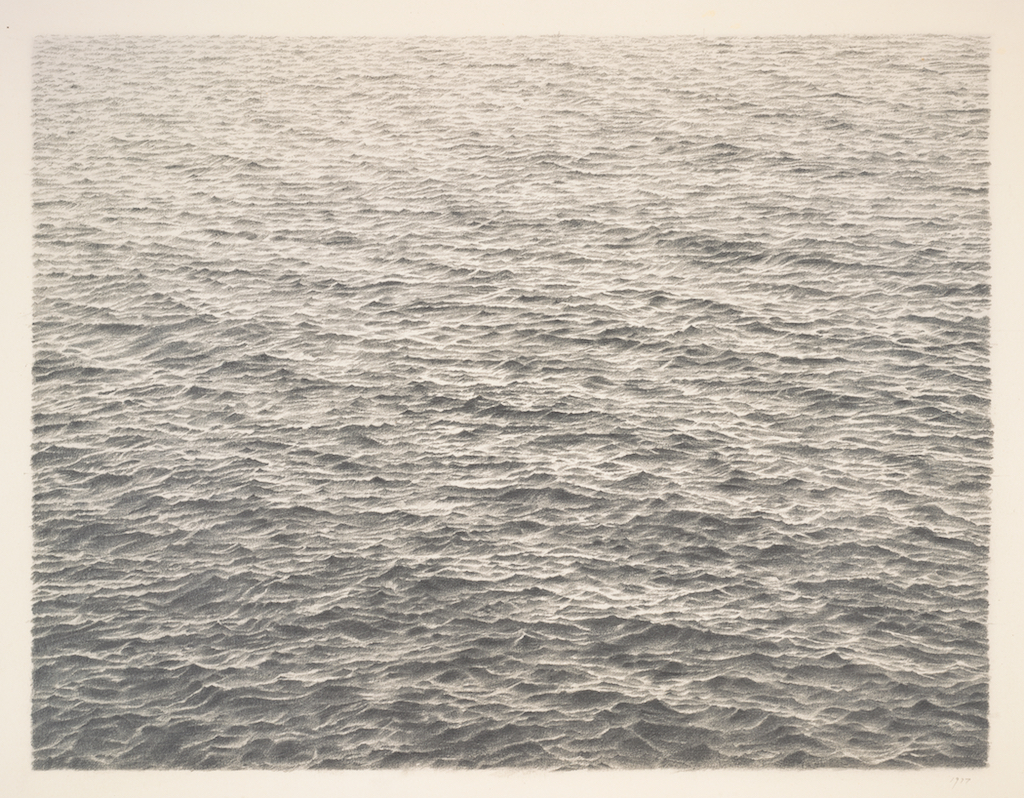

Vija Celmins, Untitled (Ocean), 1977, graphite on acrylic ground on paper.

©VIJA CELMINS/PHOTO: DON ROSS/COURTESY SAN FRANCISCO MUSEUM OF MODERN ART

The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art is home to a new retrospective of the artist Vija Celmins, whose drawings of oceans and lunar surfaces are so subtly and carefully worked that they resemble photographs. With that exhibition in mind, we have republished a short profile of the artist by Gordon J. Hazlitt, who wrote on Celmins for the February 1978 issue of ARTnews. He asks Celmins why her drawings are so obsessive. She tells him: “They are records of states of attention. When I do them, nothing is too little or too much to attend to.” —Alex Greenberger

“Vija Celmins: A reductionist by nature”

By Gordon J. Hazlitt

February 1978

Talking with Vija Celmins is instructive, for much of what is implied in mainstream contemporary art becomes explicit. Celmins has a reputation as an artist who is meticulous in the conception and execution of her work, if not prolific. In recent years she has worked solely with graphite pencil, drawing small, semi-abstracted patches of ocean on desert floor.

Her studio, located in an industrial section of West Los Angeles, is still new and alien to her, and the dislocation has severely interrupted her concentration and output. She lives in a small apartment she fashioned upstairs but draws in a long warehouse room which is painted flat white and seems virtually empty.

Celmins thinks as clearly as her drawings are rendered and speaks with candor. “I am a reductionist by nature. I like to throw away what doesn’t concern me anymore. When I was a student I painted like de Kooning, but I tired of the huge scale and all the endless juxtaposition of little marks. I gave up cold because I found I really didn’t like it. Then I gave up painting entirely.”

About ten years ago, she saw a photograph taken by of the moon’s surface by one of the Russian space missions. The distanced, flat-appearing landscape triggered a response: “I had wanted a closer contact with the surface than I was getting through brushwork in painting. She began to work with pencil, drawing sky, sea or landscapes that were as “tight” as she could get them. Working with pencil proved satisfying because the pencil’s point sharply focused her attention throughout the process.

Vija Celmins.

ERIN MCNATT/COURTESY SAN FRANCISCO MUSEUM OF MODERN ART

“I deliberately sought neutral images, in that the image as such, would be only one element among many and would balance with other qualities such a density, proportion or scale.” She now finds some of her earlier drawings of the surface of the sea “baroque” because they have a somewhat dramatic, individualized look. The new drawings, of sea or desert floor, are much “tighter,” more nearly pure surface. She has not dropped the image of sea or desert entirely because she believes that “illusion per se is inherent in art and must be dealt with but must not allowed to dominate.”

Celmins now often works in series. She will do two or more drawings of the same image, varying one of the few elements she keeps in her work. Taking a cue from Monet’s series of paintings of haystacks done in different light, she has done several extended series of drawings of galaxies and ocean in which she repeats the image as exactly as possible but varies the hardness of the graphite in her pencil. The completed work is a subtle spectrum of drawing. At other times, she will draw the same image at two contrasting scales on the same piece of paper. In all such series, the real content of the work is in the viewer’s perception of the difference the alteration makes.

Celmins is highly ambivalent about California as a place to work, though she speaks of enjoying the proximity to the actual sea and deserts. She says, “I feel real isolated here. Los Angeles is a dead town for art and lacks a good context for doing serious work.” When asked to contrast it with New York, she added that the problem is that “maybe in New York the context is too developed and artists get put in tight categories.”

How should her drawings be interpreted? “They are records of states of attention. When I do them, nothing is too little or too much to attend to. I hope people feel that nothing is hidden in them.”

[ad_2]

Source link