[ad_1]

To close out Black History Month, HuffPost wanted to reflect on black historical moments and figures whose influence has been and will be made evident throughout 2019. Among the four listed are people whose audacity, success, stature or some concoction of the three transformed them into figures whose impact is still being felt today.

Hattie McDaniel

In 1940, when Hattie McDaniel became the first black person to win an Academy Award for her role in ”Gone with the Wind,” her victory was not unanimously celebrated among black people. McDaniel, who up to then had made a career of playing maids on-screen, was excoriated by the NAACP and black people of their ilk who claimed her “Mammy” character demeaned black people by leaning into stereotypes.

They also took exception to McDaniel winning an Oscar for a film seen as sympathetic to the Confederacy. But with the benefit of hindsight, and given the film industry’s longstanding stubbornness toward telling new black stories, McDaniel is widely appreciated today as a black historical figure who broke through and endured substantial humiliation in the process. In theory, the near-century since her victory was to bring a wave of new, progressive, rich black characters in film, along with compelling new storylines. At times, that has been the case. At other times, not so much. Our discussions about black actors in film, the accolades they receive and why they receive them were precipitated by Hattie McDaniel, and as those discussions continue to play out, her history ought to be at the front of everyone’s mind.

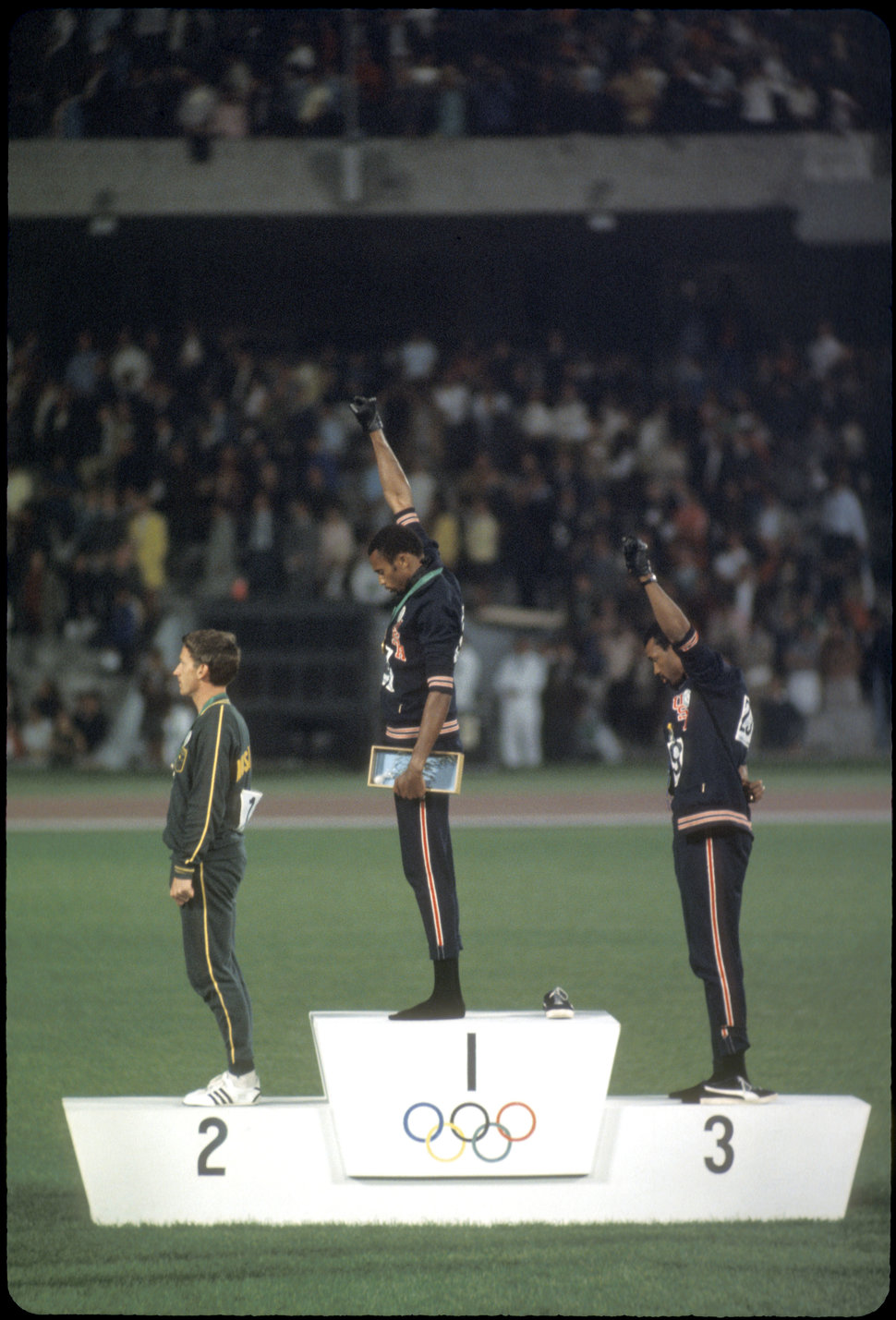

Tommie Smith and John Carlos

Tommie Smith and John Carlos were made global pariahs when the two raised their fists in silent protest during the 1968 summer Olympics. Donning black gloves, Smith and Carlos stood on the podium after placing first and third respectively in their 200-meter race and hoisted their fists to the sky, showing solidarity with black people experiencing racism in the U.S. In response, the two men were expelled from the Olympic Village, the head of the International Olympic Committee denounced their actions as “deliberate and violent,” and they received death threats when they arrived back in the states.

But as is the case with civil rights icons like Martin Luther King, Jr. and Muhammad Ali, Tommie Smith and John Carlos have seen their public favorability rise the further we’ve moved from the day of their actual stance. Their stories are now the stuff of celebratory ESPN features rather than simple fodder for bigots, and people who may have castigated the two previously have been shamed into praising them — or remaining silent — as society has changed. That character arc is instructional in our time, when athletes are becoming more vocal about inequality and facing potential banishment as a result. It will be fascinating to witness the ways in which many who oppose these athletes now will reimagine their stance when they’re asked about it later.

Congressional Black Caucus

The Democratic Select Committee — that is, the group of black representatives in the House that eventually became known as the Congressional Black Caucus — formed 50 years ago, in 1969. That group of black representatives included names like Shirley Chisholm and founding member William Clay, who notably declared “Black people have no permanent enemies, no permanent friends … just permanent interests.” In the 50 years since, the Congressional Black Caucus has functioned as a nonpartisan conduit through which black representatives in the House and Senate can usher policies focused on their black constituents. And effectively, the Congressional Black Caucus has served as a feeder of sorts, initiating black Congresspeople into the day-to-day operations of both chambers while allowing some to elevate their stature. From John Lewis, to Maxine Waters, to Barack Obama (who was in the Caucus as a senator), the Congressional Black Caucus is largely responsible for providing platform to representatives who may have otherwise struggled to gain footing in a predominantly white Congress.

Rep. Barbara Jordan (D-Texas)

In 1972, Barbara Jordan became the first black woman from the South elected to the House of Representatives. Jordan, who died in 1996, was a titanic voice in the most literal of ways. Her timbre was hearty, deep and resonant, and only two years after Jordan assumed her seat in the House, she wielded that voice in delivering perhaps the most damning, memorable speech delivered throughout all of the Nixon impeachment proceedings.

If Nixon’s actions did not defy the Constitution and warrant impeachment, Jordan argued, “perhaps that 18th-century Constitution should be abandoned to a 20th-century paper-shredder.”

Her 13-minute speech marked the first occasion on which a black woman would speak such truth to power from the dais of the House Judiciary Committee, and her forcefulness in that speech helped precipitate Nixon’s eventual resignation only months later. The similarities between then and now are clear. Today, America finds itself again embroiled in a constitutional crisis involving the president. And a host of women of color are electing to speak frankly and authoritatively about our predicament. In that vein, Barbara Jordan is evidence that these women — while forging their own paths — are also drawing from a rich history of unapologetic speaking.

[ad_2]

Source link