The Story of the Teacher Who Integrated New York Transit | Atlas Obscura

This story is excerpted and adapted from Jerry Mikorenda’s book, America’s First Freedom Rider: Elizabeth Jennings, Chester A. Arthur, and the Early Fight for Civil Rights.

— Jerry Mikorenda, Atlas Obscura

Eighteen fifty-four was a year of extremes in New York City. As noted in the New York Daily Times, “it was remarkable for wrecks, murders, swindles, defalcations, burnings on sea and land.”

The year began with high hopes for a long-awaited railroad line on Broadway and ended with the arrests of several officials from the Harlem Railroad Company for stealing. By midyear, the first Cholera Hospital opened at 105 Franklin Street, followed by another on Mott Street, only to have the commissioners of health accused of suppressing data about cholera deaths as fear of an epidemic gripped Manhattan.

In a city of 515,000 residents, 500 children died the week of July 15—two-thirds were infants. Of the 817 New Yorkers to die overall, 12 were recorded as “colored.” About a mile or so uptown, Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman in America to receive a medical degree, was busy establishing the New York Dispensary for Poor Women and Children by the newly rising tenements near Tompkins Square Park. At first, no one trusted a female doctor. But within two years, abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison helped her raise enough money to purchase the old Roosevelt home at 64 Bleecker Street and expand her services. (Today it’s known as New York-Presbyterian/ Lower Manhattan Hospital.)

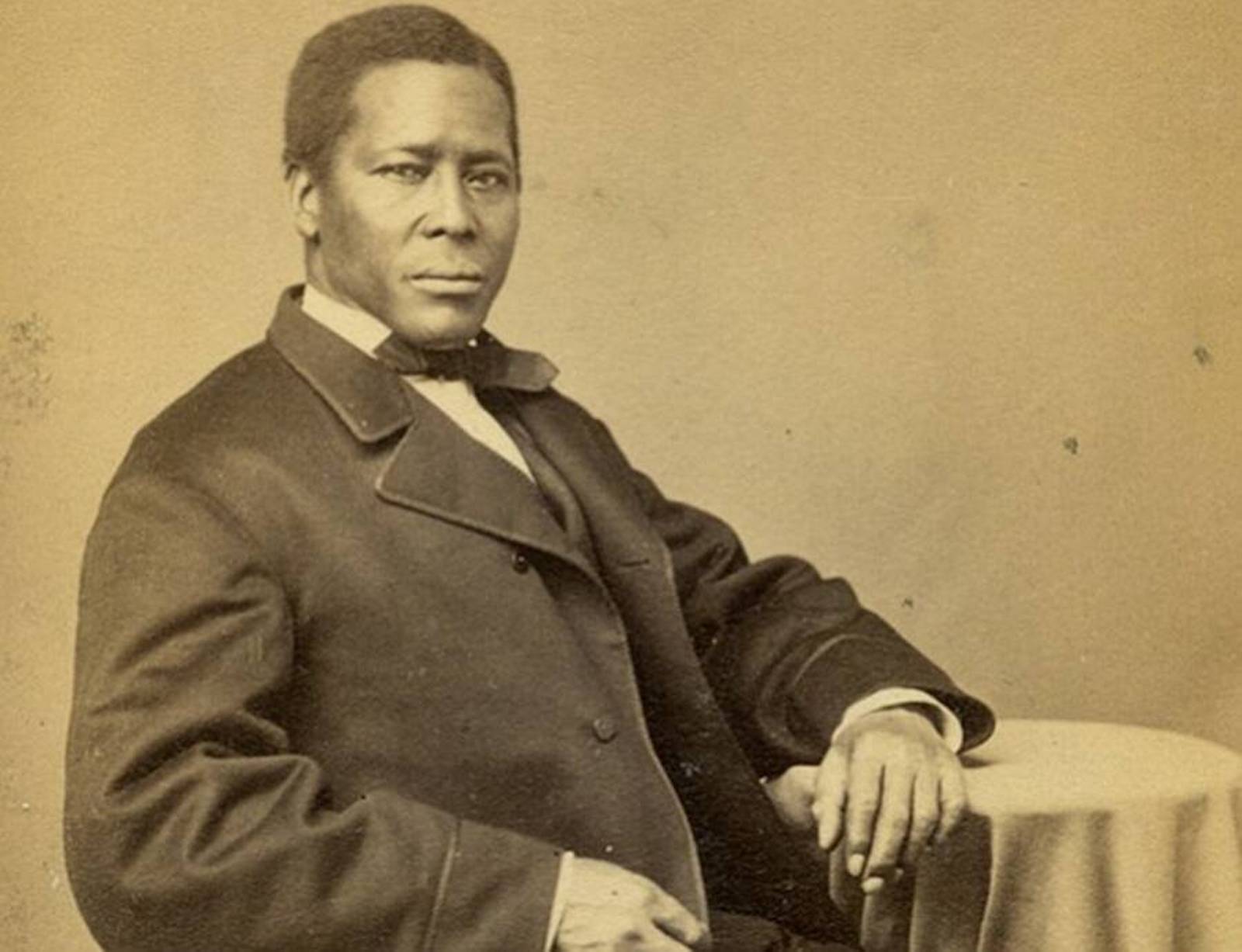

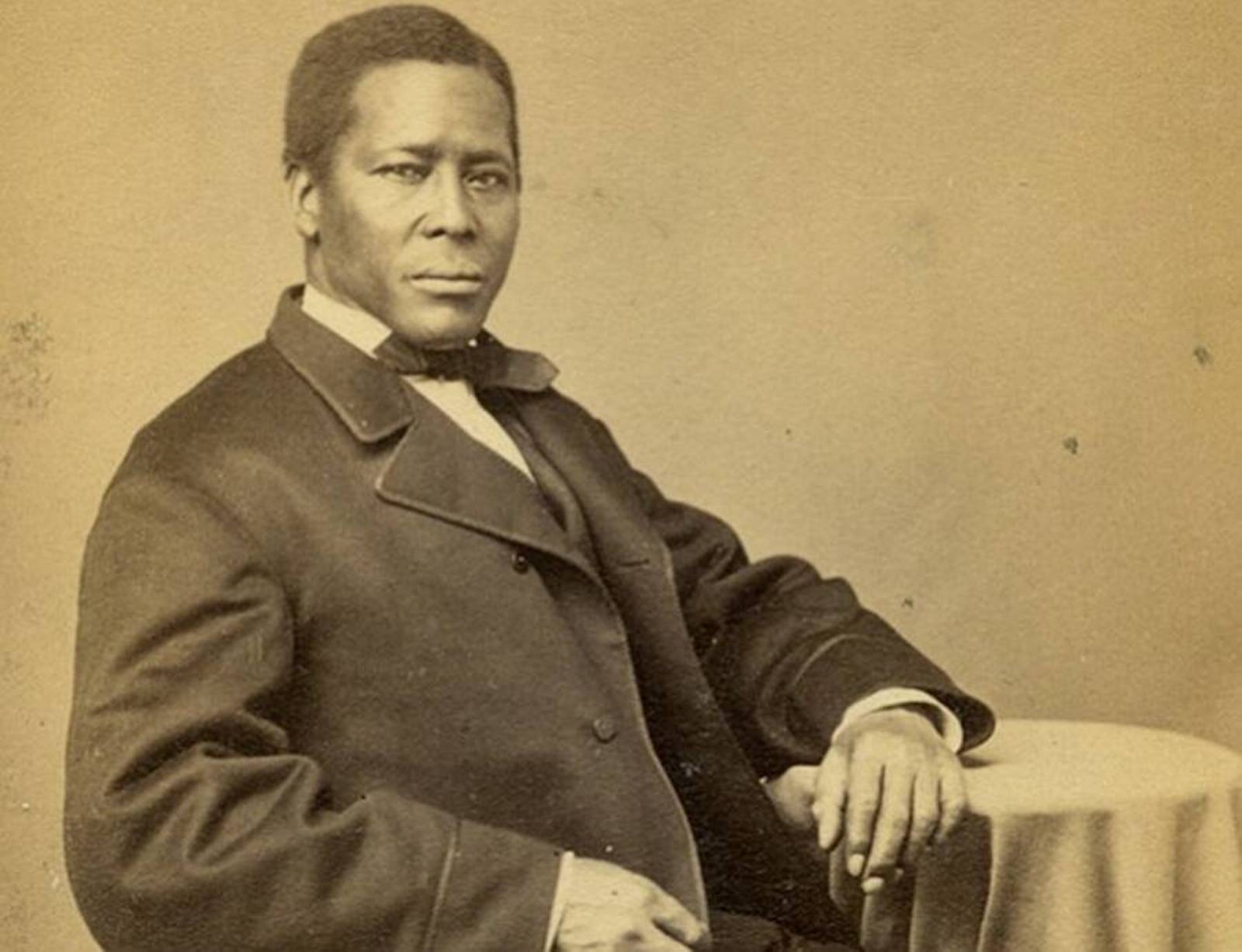

Featured Image, Kansas State Historical Society

Full article @ Atlas Obscura

Published at Mon, 07 Sep 2020 16:05:05 +0000